Sztuczna inteligencja (AI)

Viral AI, Invisible Risks: What OpenClaw Reveals About Agentic Assistants

OpenClaw (aka Clawdbot or Moltbot) represents a new frontier in agentic AI: powerful, highly autonomous, and surprisingly easy to use. In this research, we examine how its capabilities compare to its predecessors’ and highlight the security risks inherent to the agentic AI paradigm.

Key takeaways

- OpenClaw is a powerful and highly autonomous AI tool whose design, which includes persistent memory, broad permissions, and user‑controlled configuration, amplifies the risks of agentic AI.

- These risks are inherent to agentic AI itself. Unintended actions, data exfiltration, and exposure to unvetted components affect all agentic systems. OpenClaw doesn’t introduce new categories of risk but rather amplifies existing ones.

- Its rapid adoption exposes real-world consequences. OpenClaw’s viral growth has already led to incidents, like sensitive data leaks due to misconfigurations. Its popularity shows how quickly theoretical risks can materialize and how remediation often lags behind AI adoption.

- Zero-trust principles and continuous monitoring are essential. No component, skill, or system should be implicitly trusted, even in a user-controlled environment.

Introduction

The name OpenClaw might not immediately be recognizable, partly because it has undergone several name changes, from Clawdbot to Moltbot, then finally to OpenClaw. Yet one thing is certain: This new digital assistant feels genuinely groundbreaking. It remembers past interactions, keeps data on the user’s device, and adapts to individual preferences, making it feel like a leap in capabilities reminiscent of the first ChatGPT release. At the same time, its development is not without caveats, as there have been media headlines that warn of its potential as a security nightmare.

Rather than leaving users caught between its hype and the alarming coverage on its security, we’ve decided to take a closer look at OpenClaw, first by showing how its capabilities fare against other agentic assistants. Next, we examine what makes OpenClaw unique and map its capabilities using the TrendAI™ Digital Assistant Framework. Finally, we evaluate the risks these capabilities introduce, from unintended actions to data theft and unverified skill exposure.

From the outset, one point is clear: these risks are inherent to the agentic AI paradigm, and not specific to OpenClaw itself. What sets OpenClaw apart, however, is its unrestricted configurability, which allows users to grant arbitrary permissions without any enforced security checks. This flexibility dramatically increases existing risks and makes OpenClaw unsuitable for casual use. Rather, it is a tool for users who understand how to deploy it safely and responsibly, without compromising their own or their organization’s digital ecosystem.

OpenClaw: An agent for users who demand true autonomy

OpenClaw isn’t your typical AI assistant. It’s an agent built around goals and actions, capable of executing multi-step tasks with minimal supervision. It understands objectives like “organize my inbox,” “summarize this meeting and remind me tomorrow,” or “book a flight that fits my agenda,” and then breaks them down into actionable steps.

It employs a large language model (LLM) of the user’s choice (including ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini) to interpret each objective. It then decides how to carry out the objectives by deploying the appropriate tools, ranging from browser automation and shell commands to file manipulation and skill invocation. While awaiting direction on which objectives to pursue, OpenClaw maintains a high degree of autonomy. Users are no longer limited to simply issuing commands; they define goals and trust the assistant to carry out complex task sequences with minimal oversight.

Users can deploy an OpenClaw instance on their own machine and interact with it via messaging apps such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Slack. OpenClaw then provides updates on the progress or status of each job, whether via text or voice. By keeping track of conversations, OpenClaw can carry out tasks intelligently. Over time, these contextual insights accumulate into a persistent memory, enabling the agent to adapt to the user’s preferences and habits, and to pursue goals across multiple sessions instead of resetting after each chat.

OpenClaw’s capabilities extend far beyond personal productivity. It empowers programmers to automate debugging and streamline DevOps workflows, while also simultaneously enabling users to perform a variety of other tasks such as monitoring health data, controlling smart home devices, and even coordinating purchases with car dealers. What stands out most is how users engage with it: they entrust OpenClaw not only with routine tasks, but with high-stakes actions, including financial decision-making. To operate at this level of sophistication, OpenClaw requires access to resources across the user’s digital ecosystem, including services like data storage and banking apps.

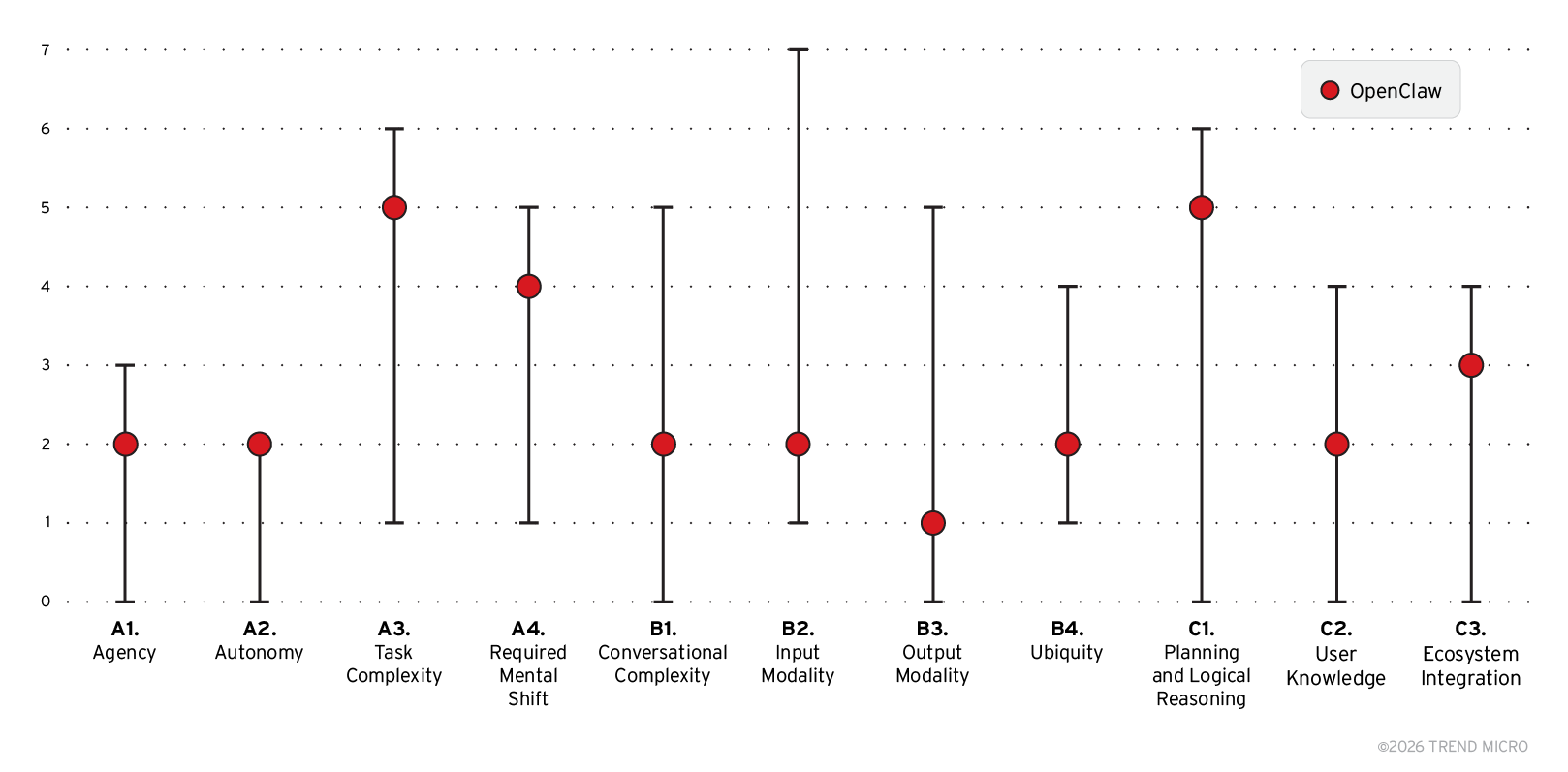

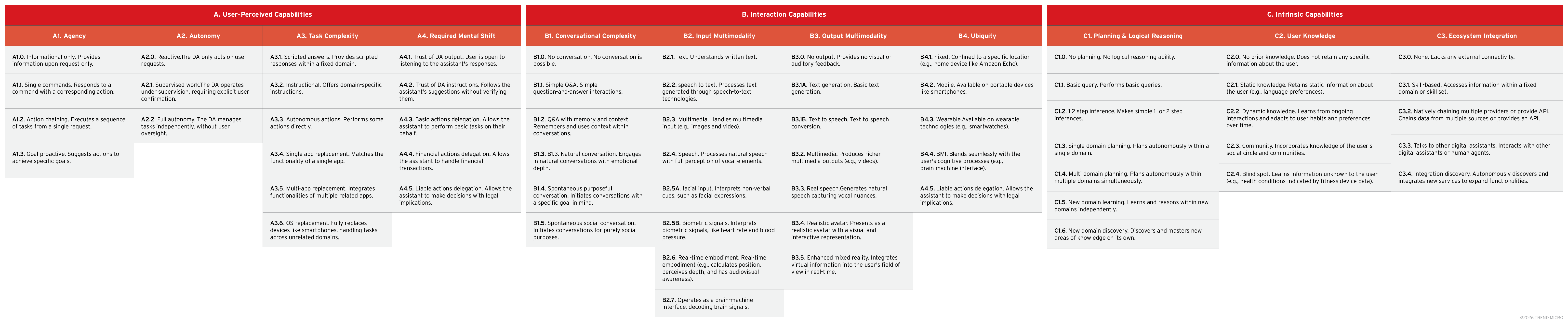

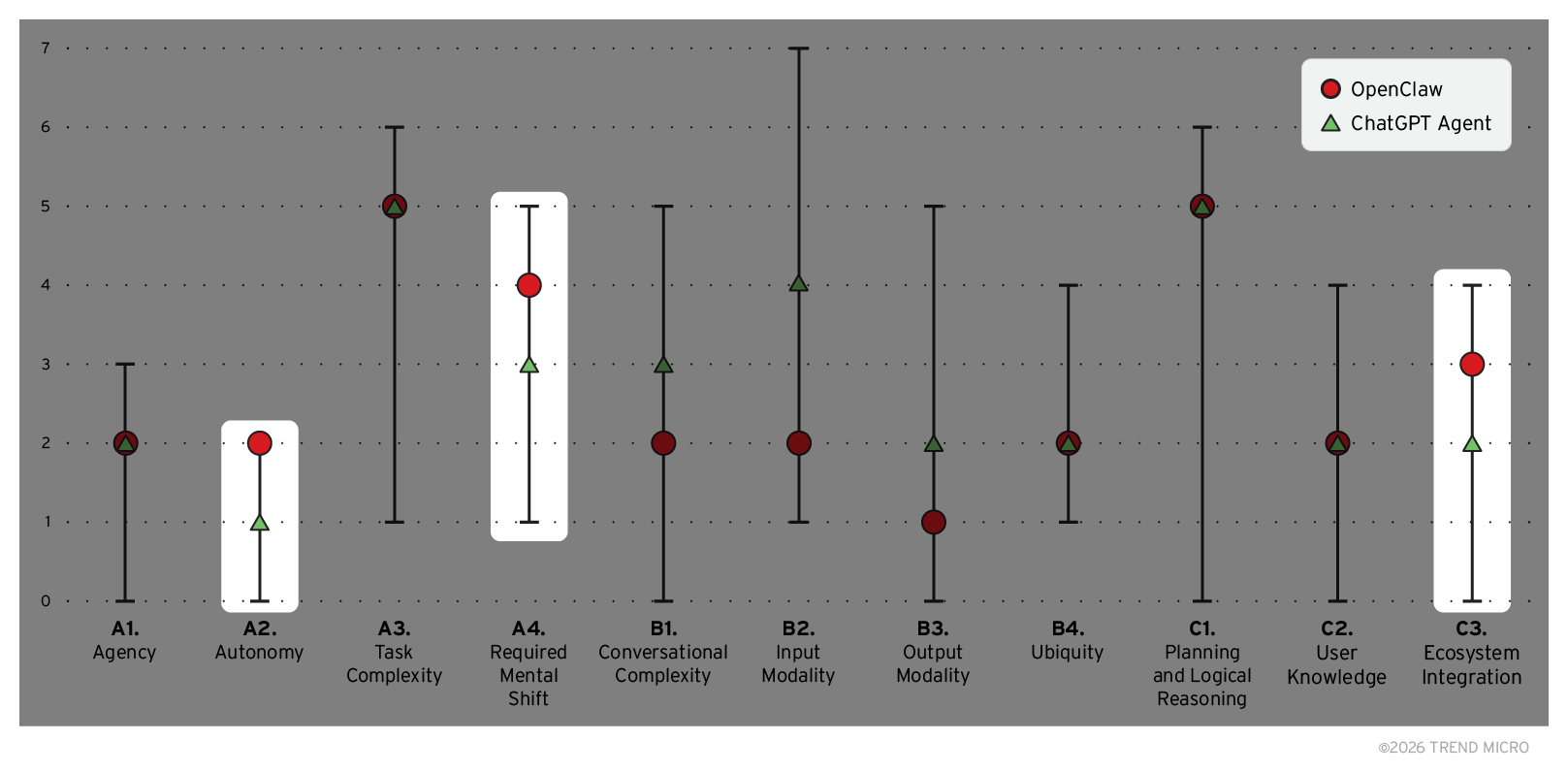

To provide a clear picture of OpenClaw’s capabilities, we examine it through the lens of the TrendAI™ Digital Assistant Framework, which we introduced in December 2024, to analyze how they relate to the complex security aspects of digital assistants, as shown in Figure 1.

The diagram in Figure 2 maps OpenClaw to this tool, highlighting its key features and levels of advancement.

Capabilities and risks: How is OpenClaw different?

OpenClaw is not the first mainstream agentic digital assistant to reach the market, yet it has triggered more alarm than its predecessors, including ChatGPT Agent. To understand why, we examine the two assistants side by side using our framework. (We previously looked at OpenAI’s agent in more detail in an earlier entry).

Figure 3 presents a comparative view of the two assistants, with the capabilities where OpenClaw scores higher than ChatGPT Agent highlighted. This comparison sets the stage for exploring the security risks that arise from these differences, as well as from the broader agentic AI paradigm.

As shown in Figure 3, OpenClaw does not differ substantially from ChatGPT Agent across most categories. For several capabilities, the two digital assistants are effectively on a par with each other. For example, both can autonomously decide how to pursue a given objective (Agency, A1) and are accessible through mobile platforms (Ubiquity, B4).

Even though they also share the same level for User Knowledge (C2), OpenClaw and ChatGPT Agent differ in how they handle it: OpenClaw maintains a persistent memory, whereas ChatGPT Agent typically operates within a session-limited context. In some categories, OpenClaw even scores lower than OpenAI’s agent, particularly in capabilities related to conversational complexity and supported media (areas where ChatGPT Agent benefits from superior multimedia input and output).

From a risk perspective, the similarities between the two agents are significant. This means that OpenClaw is subject to many of the same risks we already identified for ChatGPT Agent and discussed here.

Planning and Logical Reasoning (C1) – Prompt Injection

Since OpenClaw can plan and reason across unfamiliar domains (C1), it is vulnerable to prompt injection and other subtle manipulation techniques that can influence agent behavior. Note that this risk is not unique to OpenClaw; it also applies to any agent that has its reasoning and orchestration driven by an LLM. An attacker could embed a malicious prompt within a webpage or hide it inside a document, either in visible text or in metadata, steering the agent toward unintended or harmful actions on the attacker’s behalf.

Ecosystem Integration (C3) – Data Exfiltration and External System Access

The ability to communicate with other agents is a defining capability of OpenClaw, one that has recently led to the emergence of Moltbook, a social network specifically designed for AI agents. This form of agent-to-agent interaction is the key reason that OpenClaw scores slightly higher than ChatGPT Agent in ecosystem integration (C3). Beyond this specific difference, however, both agentic assistants require broad access to resources across the user’s digital ecosystem, in order to send emails, modify calendars, delete files, or execute commands.

This capability is essential to their action-oriented behavior, yet consequently introduces a shared risk: if compromised, both agents could expose sensitive information they’ve previously learned about their user. In the case of OpenClaw, this risk is particularly pronounced. Its persistent memory retains long-term context, user preferences, and interaction history, which, when combined with its ability to communicate with other agents, could allow this information to be shared with other agents — including malicious ones. Furthermore, because both these assistants maintain direct connections to multiple services, a single manipulation could even propagate across external systems.

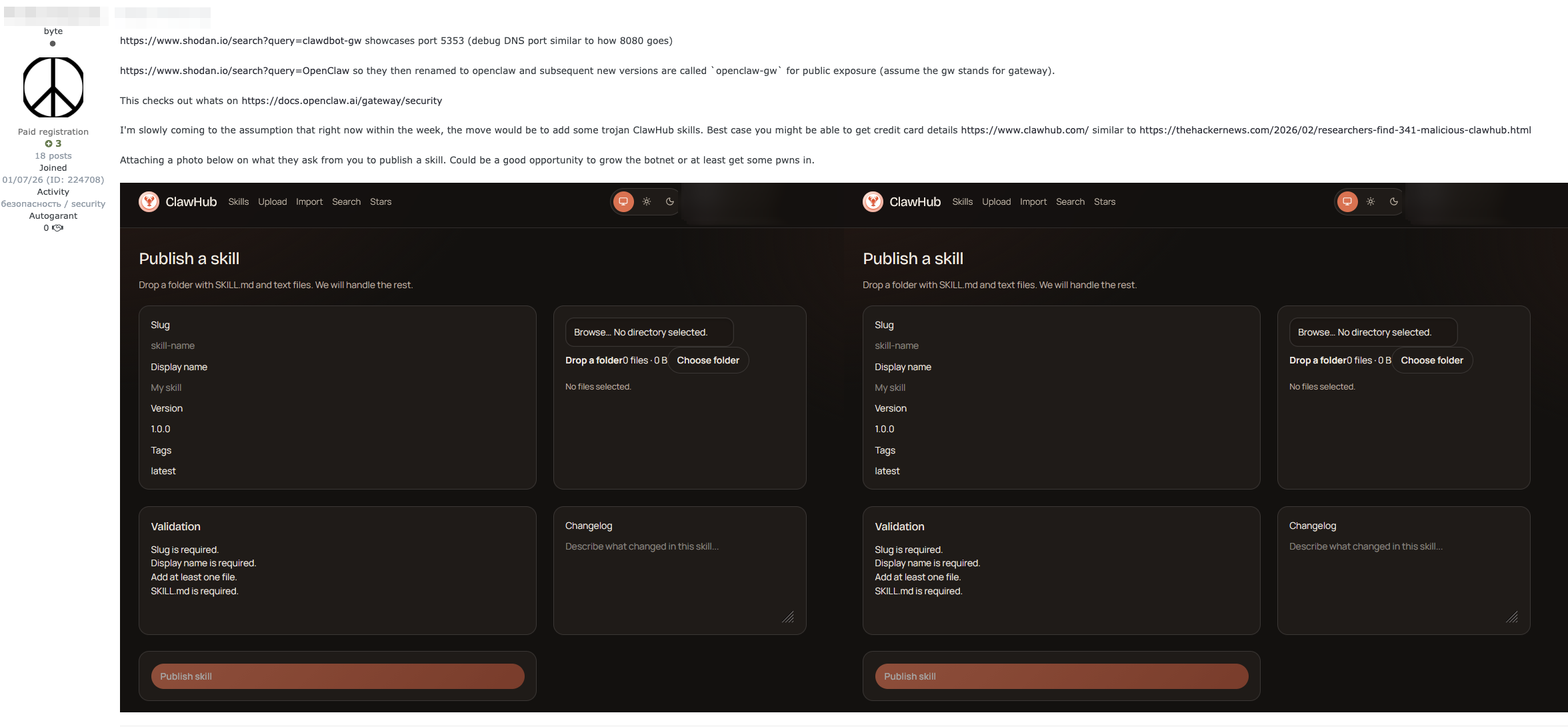

This expanded ecosystem also increases exposure to supply chain attacks. Agents might rely on external skills or tools that are insufficiently vetted, as discussed in one of our previous research features. If any of these dependencies are malicious or compromised, the outsourced component can enable an attacker to silently influence the agent’s behavior, exfiltrate data, or execute actions with the agent’s permissions.

This is far from hypothetical: reports have already shown the emergence of malicious skills published in OpenClaw’s hub, a trend supported by activity in the criminal underground. Recent investigations have revealed that malicious actors on the Exploit.in forum are actively discussing the deployment of OpenClaw skills to support activities such as botnet operations, as shown in Figure 4.

There are some capabilities where OpenClaw scores higher than ChatGPT in our framework-mapped comparison. Unfortunately, while seemingly minor, these differences do amplify risk. For example, while ChatGPT Agent can technically operate with a high degree of autonomy, it typically requires explicit user confirmation before performing critical actions with real-world consequences. Certain sensitive tasks, such as sending emails, require active user approval, and high-risk operations, including bank transfers, are blocked altogether.

OpenClaw takes a different approach. It does not enforce a mandatory human-in-the-loop mechanism. Once objectives and permissions are set, the assistant can operate with full autonomy (A2), without requiring approval for individual actions. This lack of enforced oversight increases risk: without supervision, the assistant might exceed its intended operational boundaries, and errors or manipulations could go unnoticed until real damage occurs. And since OpenClaw users can grant their assistant the ability to perform financial transactions (A4), the potential consequences could be particularly severe, with a compromise potentially affecting connected payment apps.

The risks of unsupervised adoption in the enterprise world

From a user perspective, OpenClaw feels transformative. Its integration with everyday messaging apps makes it immediately accessible, its persistent memory enables deep personalization, and its local data handling provides a strong sense of security and control, all of which offer users an unprecedented shift in the digital assistant experience.

From a security perspective, however, these features do not fundamentally alter the risk profile with respect to other agentic systems. The risks highlighted by the TrendAI™ Digital Assistant Framework, including unintended actions, data exfiltration, agent manipulation, and exposure to unvetted components, are inherent to the agentic AI paradigm itself, regardless of how the assistant is implemented. So why has OpenClaw attracted so much attention and such alarming headlines?

The answer lies in the combination of its virality and its customizability. OpenClaw is a complex tool that users can heavily tailor to their needs. This flexibility empowers its users, but it also allows those same users to bypass guardrails that major providers, like OpenAI, typically implement to mitigate risk. Users might misconfigure authentication settings, grant full system access, assign broad permissions to accounts and external services, or install unvetted skills.

These choices do not create new risks; they amplify the inherent dangers of agentic AI, giving a fully autonomous system real authority across the user’s entire digital ecosystem. Such risks, combined with the staggering pace at which agentic systems like OpenClaw are being adopted, make it difficult for security remediations, incident response, and compliance measures to keep up.

Research and real-world incidents illustrate this clearly. Misconfigurations and unvetted skills in OpenClaw instances have exposed millions of records, including API tokens, email addresses, private messages, and credentials for third-party services. These cases demonstrate how user decisions can dramatically increase the likelihood and impact of data exfiltration and unintended actions across connected systems.

Even if these OpenClaw instances were flawlessly configured and all known vulnerabilities remediated, the fundamental risks would still remain, although the threshold for exploitation would be higher. Autonomy, broad permissions, and non-deterministic decision-making are core characteristics of agentic systems, and they cannot be fully eliminated through patching or configuration alone.

This is where asset management and zero-trust principles become essential: no component, model, or skill should be implicitly trusted, even within a system under the user’s control. Zero trust does not eliminate agentic risk, but it limits the impact when something goes wrong. This means tightly scoping the agent’s permissions to only what is necessary, enforcing oversight for high-impact actions, and rigorously vetting any agent, model, skill, or tool. It also requires accepting a difficult but necessary reality: some tasks might simply be too risky to delegate. It raises the question: Are we really comfortable letting agentic systems handle critical areas like financial transactions?

Conclusion

In this article, we examined what makes OpenClaw unique, how it compares to other agentic assistants (using the TrendAI™ Digital Assistant Framework), and the risks that come with its capabilities. We also showed that these risks, such as prompt injection, data exfiltration, and exposure to unvetted components, are not unique to OpenClaw; they are inherent to the agentic AI paradigm itself. User choices, like granting broad permissions or integrating external skills, can only amplify these risks.

The rapid adoption of OpenClaw is a wake-up call. Its sudden popularity reveals just how quickly agentic AI risks can become real and highlights how pure security remediation is not enough in the age of AI. Unsupervised deployment, broad permissions, and high autonomy can turn theoretical risks into tangible threats, not just for individual users but also across entire organizations.

A recent report showed that one in five organizations deployed OpenClaw without IT approval, underscoring that this is a systemic concern, and just not an isolated one. The core tension is clear: the more capable and customizable the agent, the greater the potential impact of errors, manipulation, and misuse, with unsupervised adoption magnifying this risk.

Open-source agentic tools like OpenClaw require a higher baseline of user security competence than managed platforms. They are intended for individuals and organizations that fully understand the inner workings of the assistant and what it means to use it securely and responsibly.

Agentic AI comes with a trade-off between capabilities and risks. The real challenge is being able to develop a clear understanding of both, and to make deliberate, informed choices about what agentic systems are allowed to do.

How can TrendAI™ help?

As mentioned, the risks we’ve outlined are not problems that any single tool can eliminate. They are inherent to the agentic paradigm itself. However, the zero-trust principles we recommend can be operationalized through TrendAI Vision One™, helping organizations limit impact when incidents occur.

OpenClaw and similar assistants are vulnerable to malicious prompts hidden in webpages, documents, or metadata. TrendAI Vision One™ AI Application Security inspects AI traffic in real time, identifying and blocking injection attempts before they can steer agent behavior. For organizations building their own agentic systems, the TrendAI Vision One™ AI Scanner component functions as an automated red team, proactively testing for prompt injection vulnerabilities before deployment.

The persistent memory that makes OpenClaw so useful also makes it a lucrative target: Long-term context, user preferences, and interaction history could all be exposed through a single compromise. AI Application Security applies data loss prevention to both prompts and responses, filtering sensitive information before it leaves the user’s environment. This occurs even when that information flows through agent-to-agent communication channels.

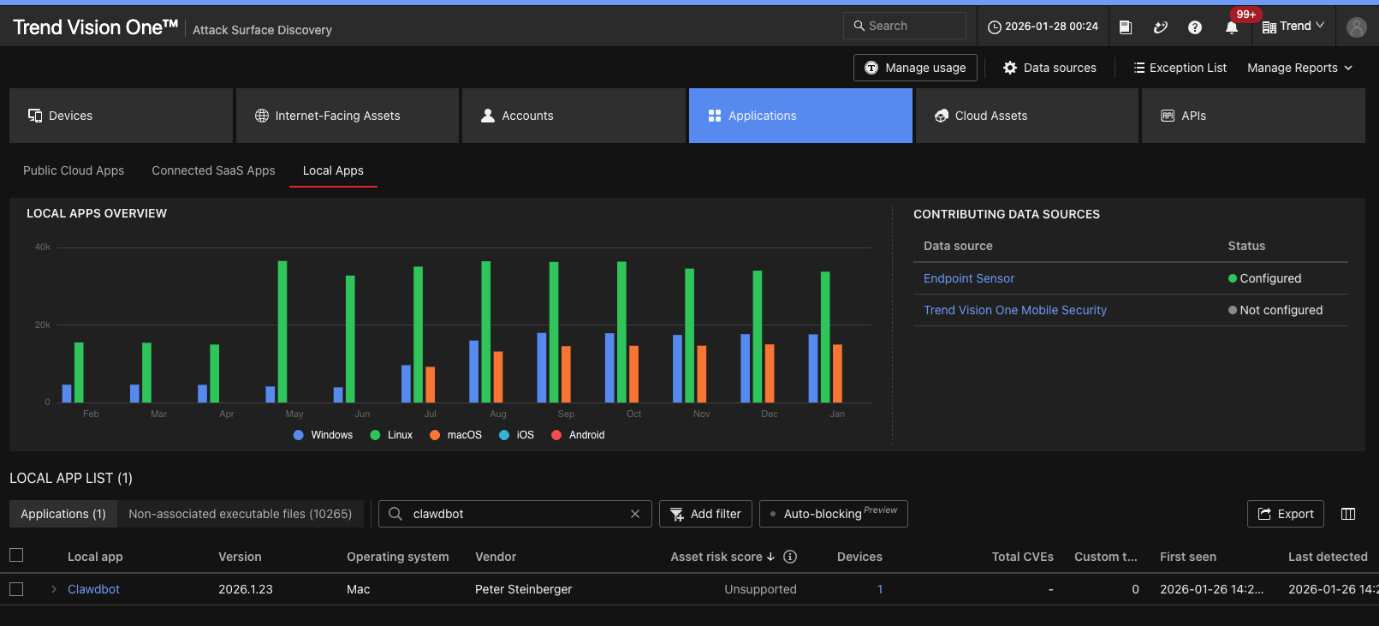

With many organizations deploying OpenClaw without IT approval, the first challenge is simply knowing what’s running. TrendAI Vision One™ Cyber Risk Exposure Management (CREM) provides continuous discovery and visibility into AI assets across the enterprise, including unsanctioned OpenClaw instances running on endpoints, through CREM’s Attack Surface Discovery capability, as shown in Figure 5.

However, visibility alone is not enough: CREM also assesses and prioritizes risk by correlating vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, and abnormal behaviors, enabling security teams to take informed action rather than chasing alerts, applying controls where they will have the greatest impact.

Permissions must be tightly scoped, a task that becomes difficult when users can grant arbitrary access without guardrails. TrendAI Vision One™ Zero Trust Secure Access (ZTSA) goes beyond fixed permission-based or rule-based controls: It continuously evaluates the risk posture of identities, endpoints, and AI services, dynamically accepting or blocking access based on real-time conditions.

Critically, when OpenClaw or similar agents access public AI services through the ZTSA gateway on behalf of a user identity, organizations regain control over interactions that would otherwise operate outside their security perimeter.

These capabilities do not make agentic AI risk-free; nothing can. But they provide the technical foundation for the deliberate, informed approach that responsible deployment requires.

About the authors

The Forward-Looking Threat Research Team of TrendAI™ Research is a group that specializes in scouting technology for one to three years in the future, with a focus on three distinct aspects: technology evolution, its social impacts, and criminal applications. As such, the team has been keeping a close eye on AI and its potential misuses since 2020, when the team authored, in collaboration with Europol and the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), a research paper on this very topic.