Network defenders are often tasked with piecing together the succession of events that enabled an attacker to access the network. To do so, they would need to ask specific questions: How did the attackers get in? What did they do in order to enter the network? What actions did they take once inside the network that allowed them to increase their access level? These are common questions incident responders need to try and answer.

Seeking the answers to these used to be relatively simple: “An employee opened a malicious email” was a common answer to the first entry question, for example. Unfortunately, finding answers is not as straightforward these days since modern criminals have upped their game considerably. Nowadays, that question often goes unanswered.

There is a new thriving business model in underground forums where so-called access brokers sell breached credentials or direct access to corporations everywhere to other criminals. Ransomware attackers, for instance, might not need to exploit a vulnerability or spam infectious emails to gain initial access — now they can just buy their way in.

Access brokers now offer what we call access as a service. These criminals provide other malicious actors a way into corporate networks for a price, paving the way for the actual damaging attacks. The existence of this new underground marketplace is the source of the disconnect between an initial corporate breach and the subsequent attacks that follow days or even months after.

Even though we call it “as a service," this is not an actual service wherein the criminals continue to provide the service after it is sold: Rather, it is something that the seller sells and then forgets. What is provided is actually more akin to a digital product. The term "as a service," therefore, comes from comparing this new model to other similar offerings, such as “ransomware as a service" (RaaS).

Access brokers in the criminal underground often advertise this service like it’s a cinema ticket: Somebody buys this ticket, and they get straight in. In reality, however, things are a bit different. For example, what exactly do customers get in exchange for their money? Sometimes, it’s access to a web shell or a similar straightforward method of getting a command prompt into the compromised network. More often than not, however, it’s just a set of credentials and a virtual private network (VPN) server to connect to.

This also allows the seller to establish trust with the buyer from the very beginning, since it’s just a matter of logging into the network on a shared remote session and showing proof of having access to network resources. This would be the equivalent of walking with the customer into the compromised premises and showing them the interiors as proof that the stolen keys are real, like a twisted digital version of a real estate broker.

In addition to examining the service itself, we also delve deeper into the business plan of ransomware operators using these kinds of offerings. Ransomware is often connected to access as a service because this criminal offering has enabled ransomware to reach new heights of infection. Ransomware is also the most commonly deployed payload once attackers finally make it inside a targeted network, thus making this class of malware worth exploring to understand how modern malicious actors get inside the network.

Where do the credentials come from?

Access brokers source the credentials they sell from many different places. Often, when they peddle their wares on criminal forums, access brokers plainly state where the credentials come from. These credentials can be in the public domain, can come from exchanges done with other attackers, from vulnerability exploitation, or from other attacks. It’s worth noting that the access brokers could have performed these attacks themselves, or they could have purchased these credentials from other malicious actors.

One of the main services that access brokers provide is credential validation. Regardless of the source of these credentials, legitimate access brokers always try to check if username and password pairs work by either trying them manually or using specialized scripts that can do this at scale. When validating credentials from a breach, access brokers often try to validate them both on the breached site and the corporate or official site. For example, in a breach involving the theoretical website socialmedia.com, the credentials of a hypothetical employee, joe@corporation.com, are out in the open. Access sellers will then check if these credentials are valid on both socialmedia.com and on corporation.com.

The following sections discuss the most frequent sources of stolen credentials. It should be noted, however, that there might be other sources that we do not know about. In the following subsections, we discuss the sources of stolen credentials that we have observed so far.

Data breaches and password hash breaking

Data breaches and password hash breaking are the most obvious methods of obtaining credentials. Over the years, there have been many instances of companies and websites losing user lists along with password hashes. Many password hackers have managed to obtain easy passwords quite quickly, and those are in the public domain, However, the most complicated ones have traditionally been more troublesome. Modern techniques have allowed some of the most complex password hashes to be cracked. Naturally, cracked complex passwords that have not been released to the public domain are the most sought after.

Users, on the other hand, might not see the need to change their favorite password if they think it’s complex enough to be uncrackable. Although some of these credentials might be useful exclusively for the breached website they come from, many corporate users reuse passwords. Once these passwords are validated, some of them can allow attackers to enter the corporate networks indicated by the domain of the user’s email address, such as the corporation.com in our hypothetical employee’s email address, joe@corporation.com.

Malware logs

Botmasters everywhere use and monetize their botnets in many ways. This includes spying on an infected user’s internet connections and collecting user credentials, among others. The stolen credentials usually end up in a malware log owned by the botmaster, which is then sold to or exchanged with logs of other cybercriminals. Access brokers buy or trade these logs in order to increase their credentials stock.

Our research into the “cloud of logs” takes an in-depth look at these activities and cloud repositories.

Vulnerability exploitation

Some access brokers might be technically proficient enough to leverage exploits in order to attack servers and obtain user credentials. Common targets often include VPN gateways and external web servers. Access brokers might also skip doing the dirty work themselves, instead purchasing these stolen credentials from attackers who have the pertinent skills and knowledge.

Opportunistic hacking

Some smaller access brokers tend to sell one-off access to their target’s system. These kinds of sellers appear to be small-time hackers or script kiddies who, upon a successful hacking attack, immediately look to monetize the obtained network access. These accesses might eventually make it into bigger stashes owned by more professional sellers. However, we often see them sold separately by the perpetrators themselves. In a similar way, some phishing operators also sell the credentials they plunder in bulk.

Setting up shop

Just like other business operators, access brokers need reliable ways for them to market their offerings. During our research, we identified a few access broker profiles. Whenever we see one of these sellers, they usually fit in one of the following groups:

- Opportunistic sellers tend to offer one-off access, typically advertising their offerings in criminal web-based forums.

- Dedicated brokers, on the other hand, have access to an array of different companies that they advertise in wider underground networks. They also reach out directly to common associates who act as affiliates.

- Online shops comprise a group of sellers who offer a variety of criminal data. These dedicated shops are not pre-analyzed and only guarantee access to a single machine, not a network or a corporation.

In the next subsections, we discuss these three types of access brokers further.

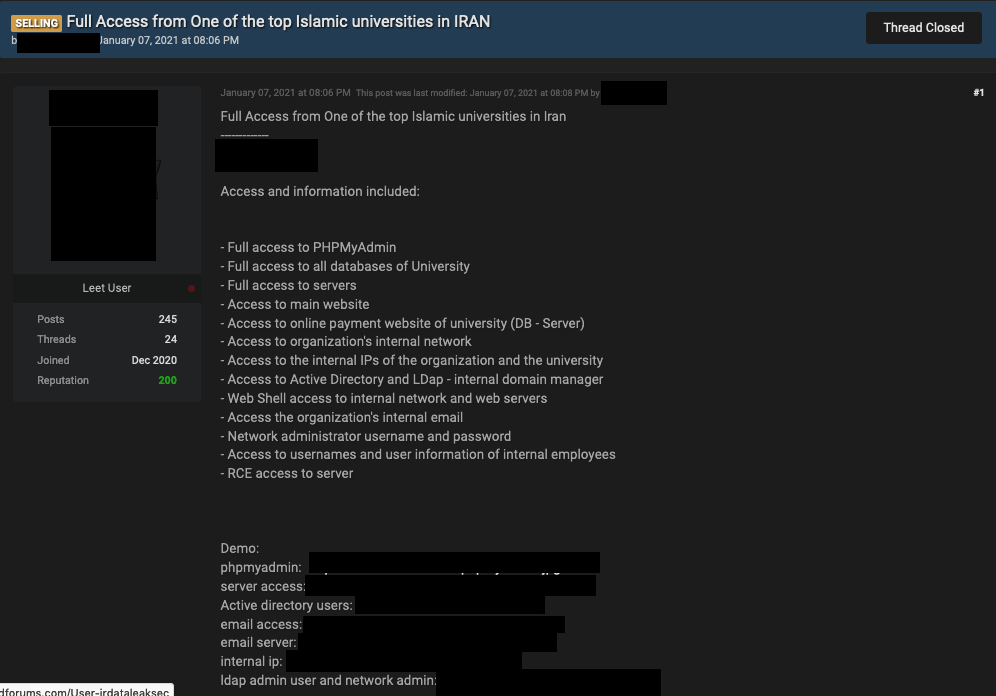

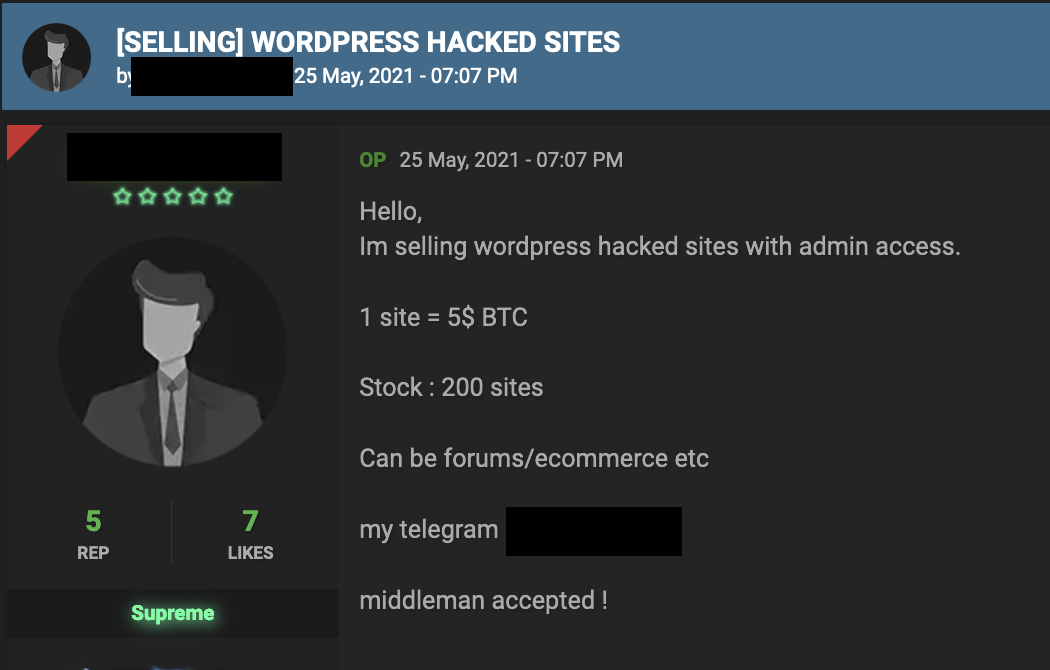

Opportunistic sellers

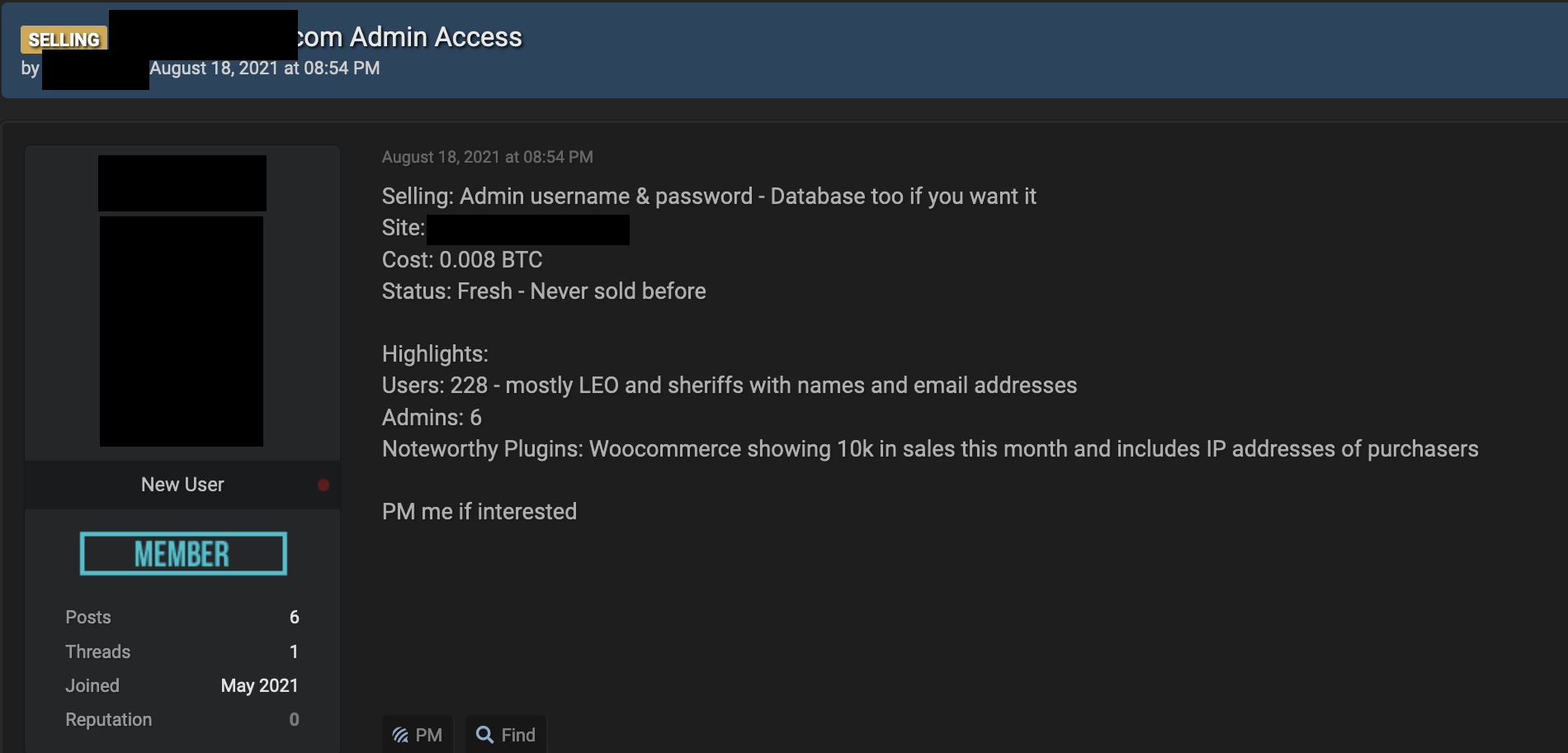

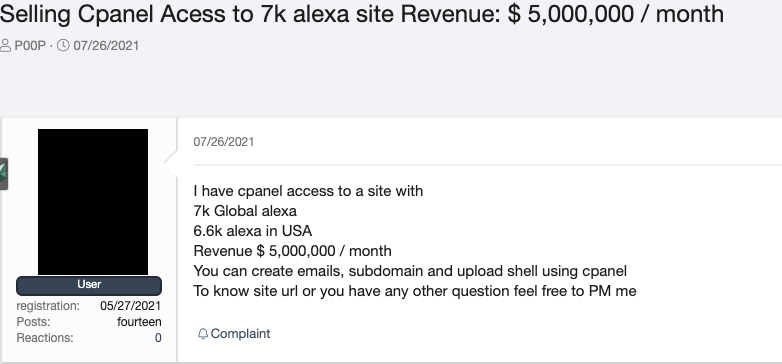

Opportunistic sellers are those that might sell a handful of access services because they were able to hack into a vulnerable network. These types of vendors are typically looking to make a quick profit. Some might be skilled hackers who want to monetize a successful operation, while others might be script kiddies who managed to pull off an attack and want to reap their reward. In both cases, these sellers do not dedicate all their time to selling access as a service in the underground. We show a case study of one such hacker selling network access later in this paper.

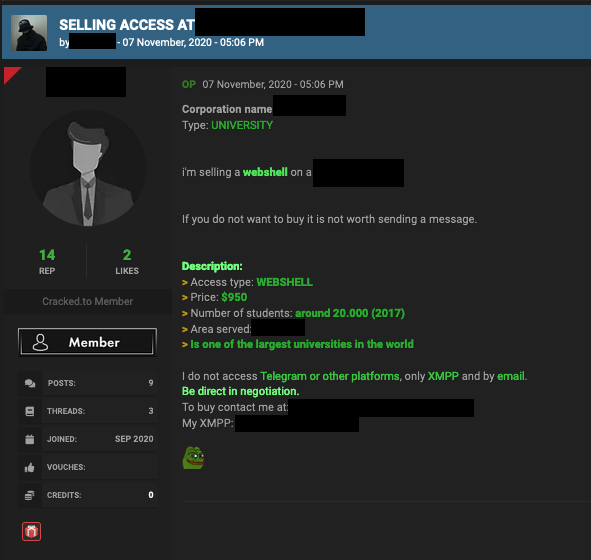

Figure 1. An advertiser in an English-language forum offering access to a university in Iran

Figure 2. An advertiser in an English-language forum offering admin access to multiple hacked sites

Dedicated access brokers

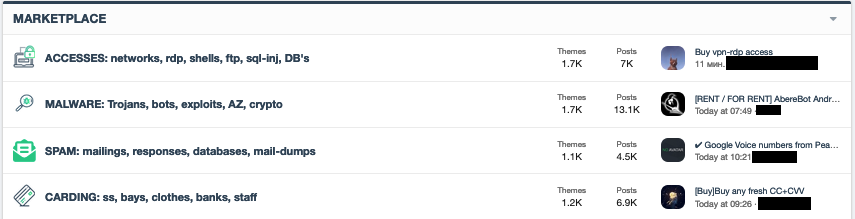

In the last two years, the demand for access brokers in criminal underground forums has increased so much that some markets now have their own category for access as a service as in the case of a popular Russian-language forum shown in Figure 3.. Access brokers peddle their wares in the sections in this figure.

Figure 3. An underground forum showing a section for access as a service (translated from Russian)

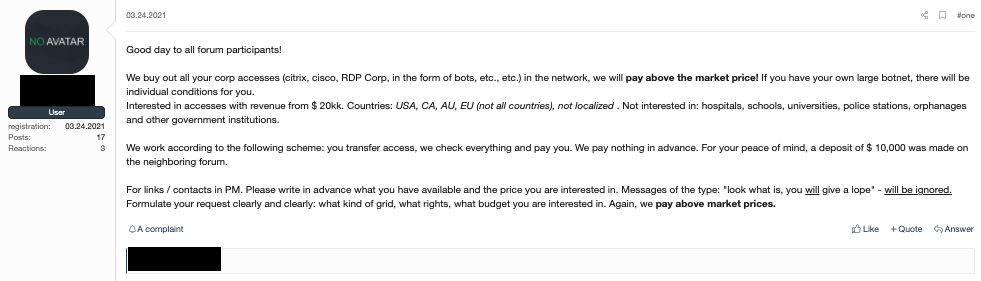

Figure 4. An advertisement on an underground forum looking to buy access services. The author is presumably an access broker trying to increase their product offerings.

Dedicated access as a service brokers tend to be sophisticated and well-skilled individuals who work alone or in small groups to maximize profits. These individuals are the ones that compromise the organizations, but are often not the same people who deploy ransomware and other types of malware. These access as a service brokers provide a valuable service to other cybercriminals, as a result of which the attackers no longer have to actually compromise or exploit organizations themselves.

While many larger ransomware groups run their own operations from top to bottom, including initial intrusion into the target networks, many ransomware affiliates and smaller threat actors might not have the resources to hack into prominent organizations and can instead use these brokers to maximize profits.

Figure 5. A dedicated access broker advertising on an English-language forum

Figure 6. A dedicated access broker advertising on a Russian-language forum (original text)

For modern large-scale attacks, attribution is often murky. In most cases, even the final attackers do not know the malicious actor that performed the initial breach. Instead, they simply purchased the credentials or some form of network access from an access broker. In these cases, the defender will not be able to determine who started the first attack or even how it was performed. In reality, when investigating the kill chain of such an attack, the defenders will be looking at two or more overlapping and potentially unrelated kill chains, making incident response difficult. For more information on this topic, we recommend two of our papers, “The Hacker Infrastructure and Underground Hosting: An Overview of the Cybercriminal Market” and “Nefilim Ransomware Attack Through a MITRE ATT&CK Lens.”

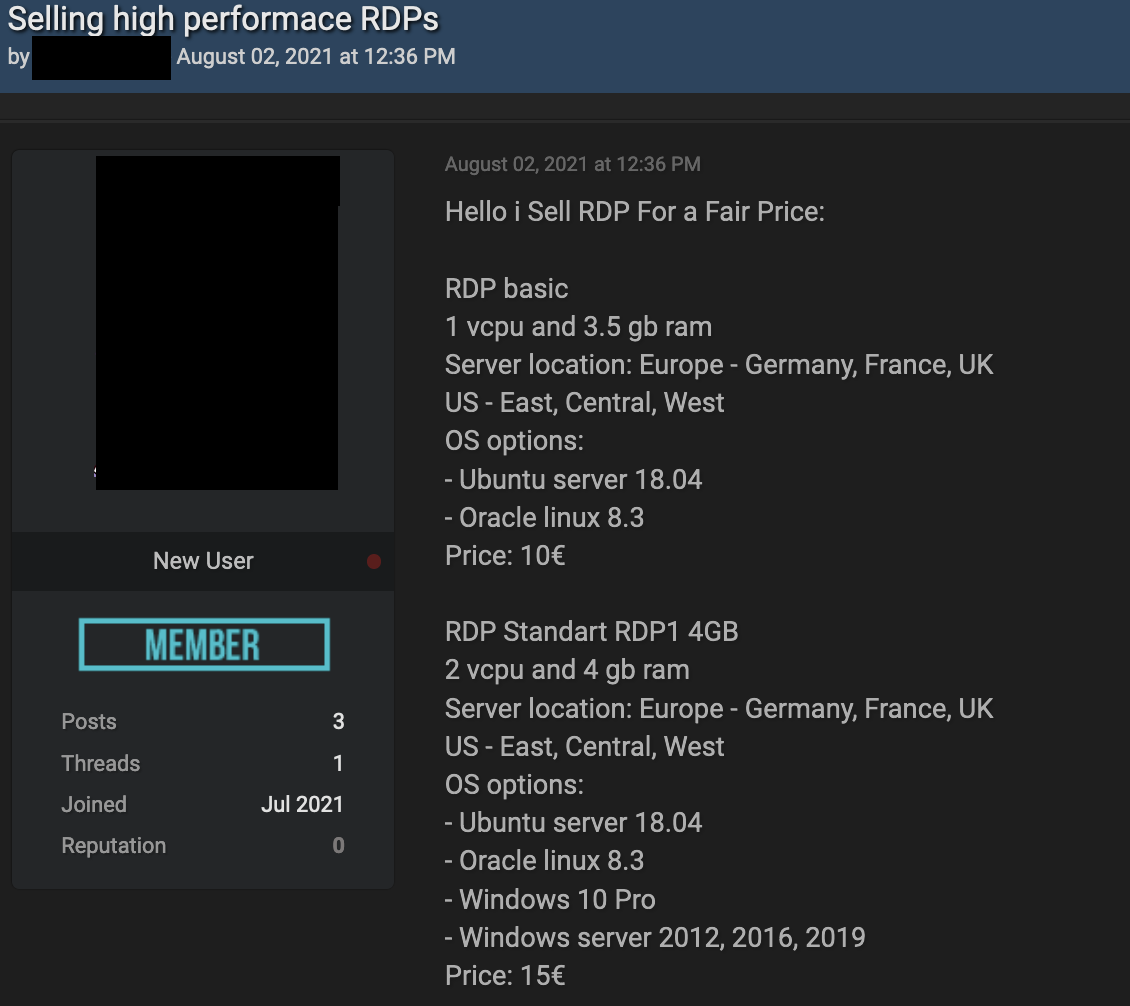

Remote desktop protocol (RDP) and VPN shops

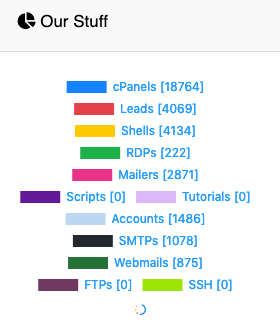

Another way for attackers to purchase access to target networks is by using the services of dedicated web shops. These shops — often contacted via Telegram — usually offer cloud repositories of stolen data that range from credit card numbers to network credentials.

Remote desktop protocol (RDP) shops, web-based stores that allow cybercriminals to purchase access credentials to compromised websites and services, typically provide the most popular offerings in this field. These shops present an endless stream of opportunities for ransomware operators and cybercriminals with lower skill sets to gain access to organizations.

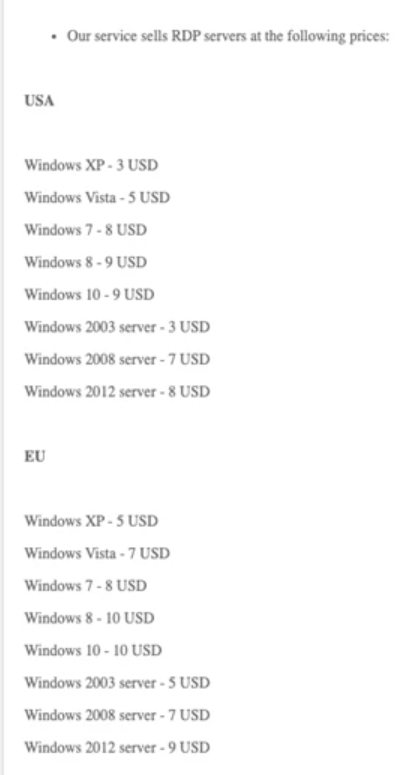

Most of these shops are automated with a “click-to-buy” option without the need for human intervention. Buyers can filter their searches from a variety of options, including by country, state, city, zip code, internet service provider (ISP), operating system, port number, and admin rights. Some shops might even filter results by corporation type or even specific company names. These attributes can be important for certain types of fraud. For instance, some fraudulent payments might only go through if the requestcomes from an IP address located in a specific zip code. Nevertheless, even though user-level credentials are mostly used for small-time scams and fraud, they can certainly be used to establish a foothold in a remote target network.

Underground cybercriminal underground markets usually advertise these RDP and VPN shop sites in forums. Several of these shops have expanded to other offerings such as SMTP, webmail, shells, FTP, cloud services, Kubernetes, Secure Shell (SSH), domain accounts, and “cpanel” access in order to cater to different attack scenarios, with prices starting at as low as US$5 for RDP offerings. Most of the time, the shops merely provide VPN accesses with user permissions. In such cases, the buyer would need to do more work in order to gain higher permissions in the network. This limitation is reflected in the cheaper price tags we see in these shops.

Figure 7. RDP shop search results showing the “latest servers.” Prices in US dollars are shown at the rightmost column.

Figure 8. Offerings from an RDP shop

Figure 9. Search options from a popular RDP shop. It’s worth noting how the search options have a “corp” yes or no field.

Figure 10. The price list from an RDP and VPN store offering RDP access to servers located in the USA and Europe

| Average market prices in RDP shops for English- and Russian-language forums | |

| Admin RDP User RDP | From US$10 From US$5 |

| VPN | From US$5 |

| Webmail | From US$10 |

| Cpanel | From US$10 |

| Shell | From US$10 |

Table 1. Average market prices for products sold in RDP and VPN shops as of August 26, 2021

Access-as-a-service underground market analysis

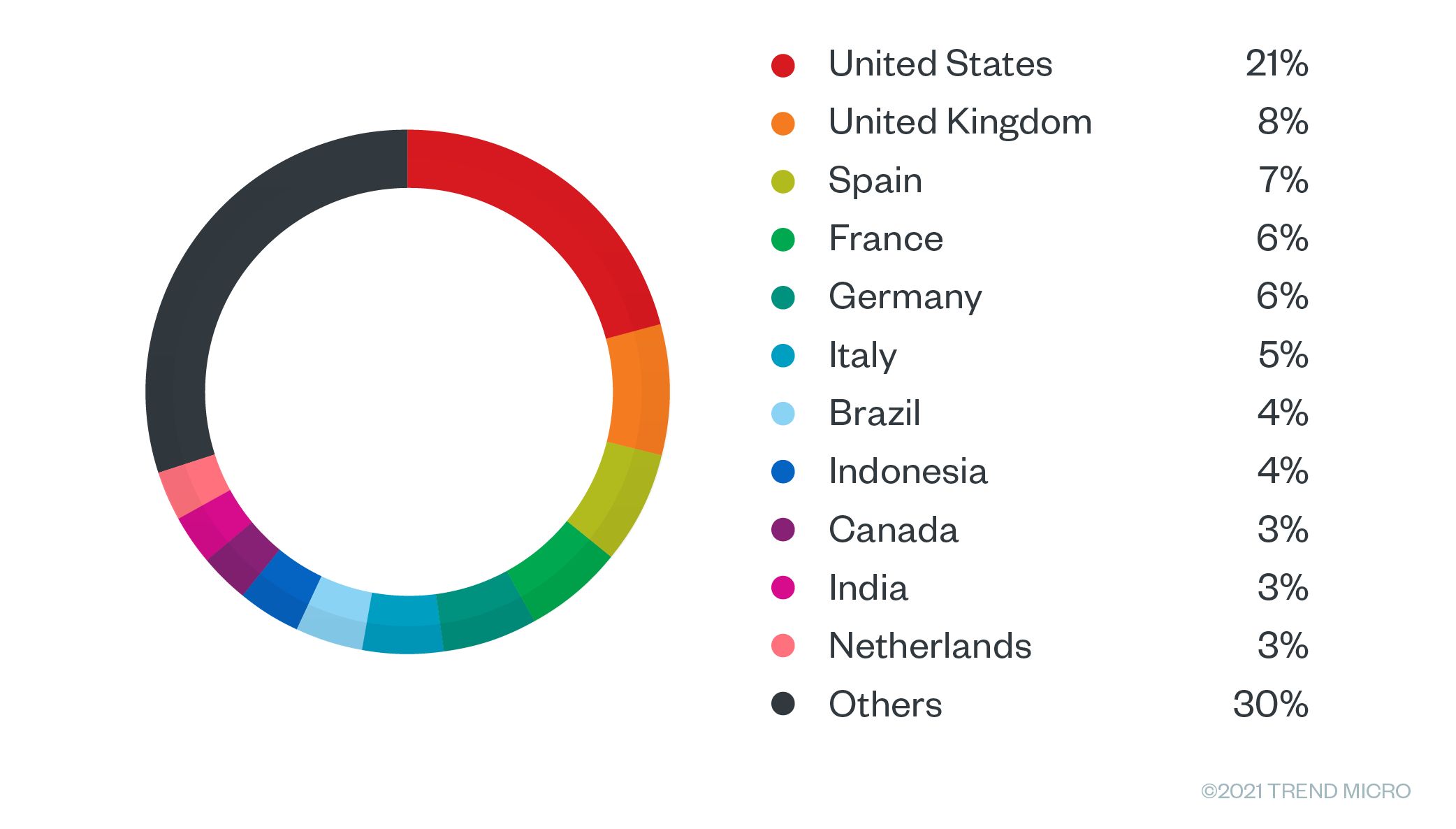

We explored over 900 access broker listings being offered for sale from January to August 2021 on multiple English- and Russian language-based underground cybercriminal forums. We did not see any significant price differences between English- and Russian-language forums. From January to August, we observed that 43% of all the advertisements for access brokers targeted businesses in the European region, followed by North America with 24% and Asia 14%.

Figure 11. Access as a service offerings by region during the last eight months

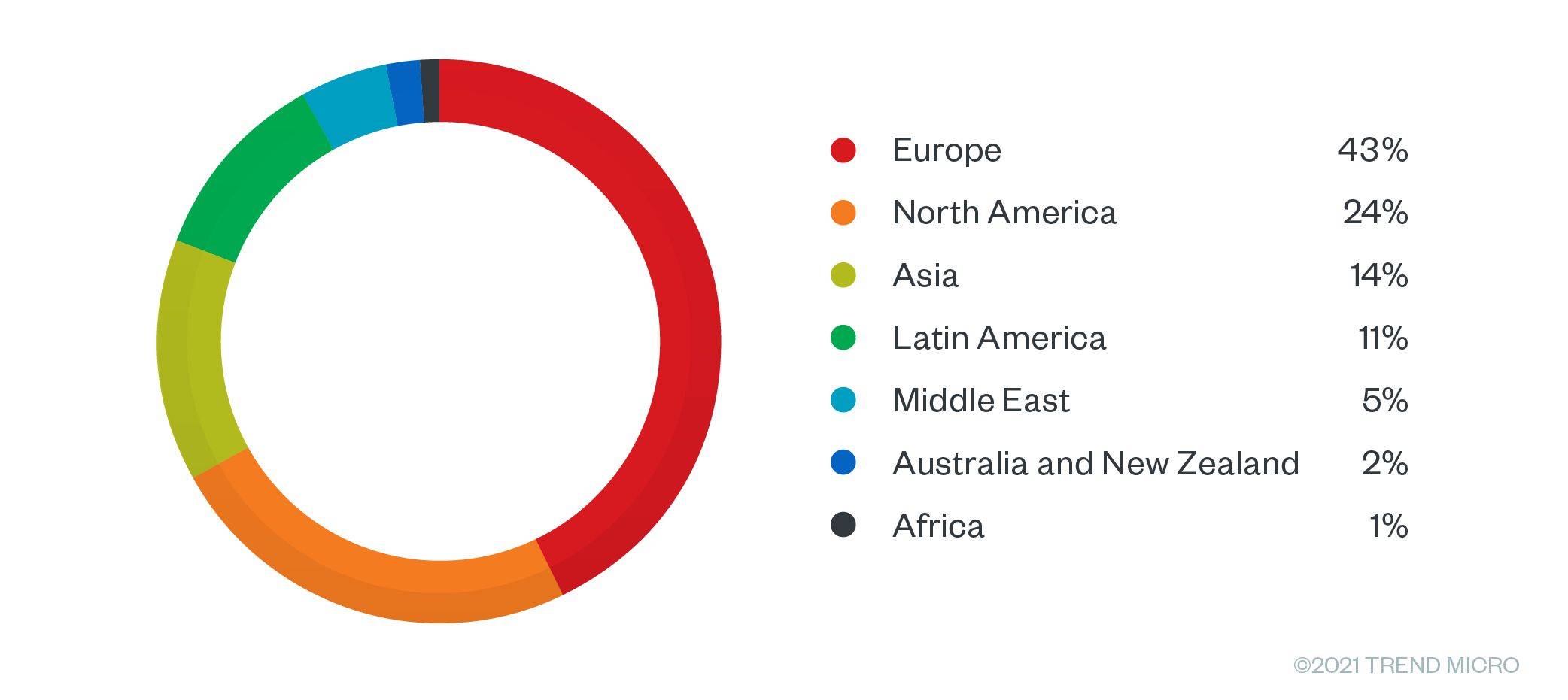

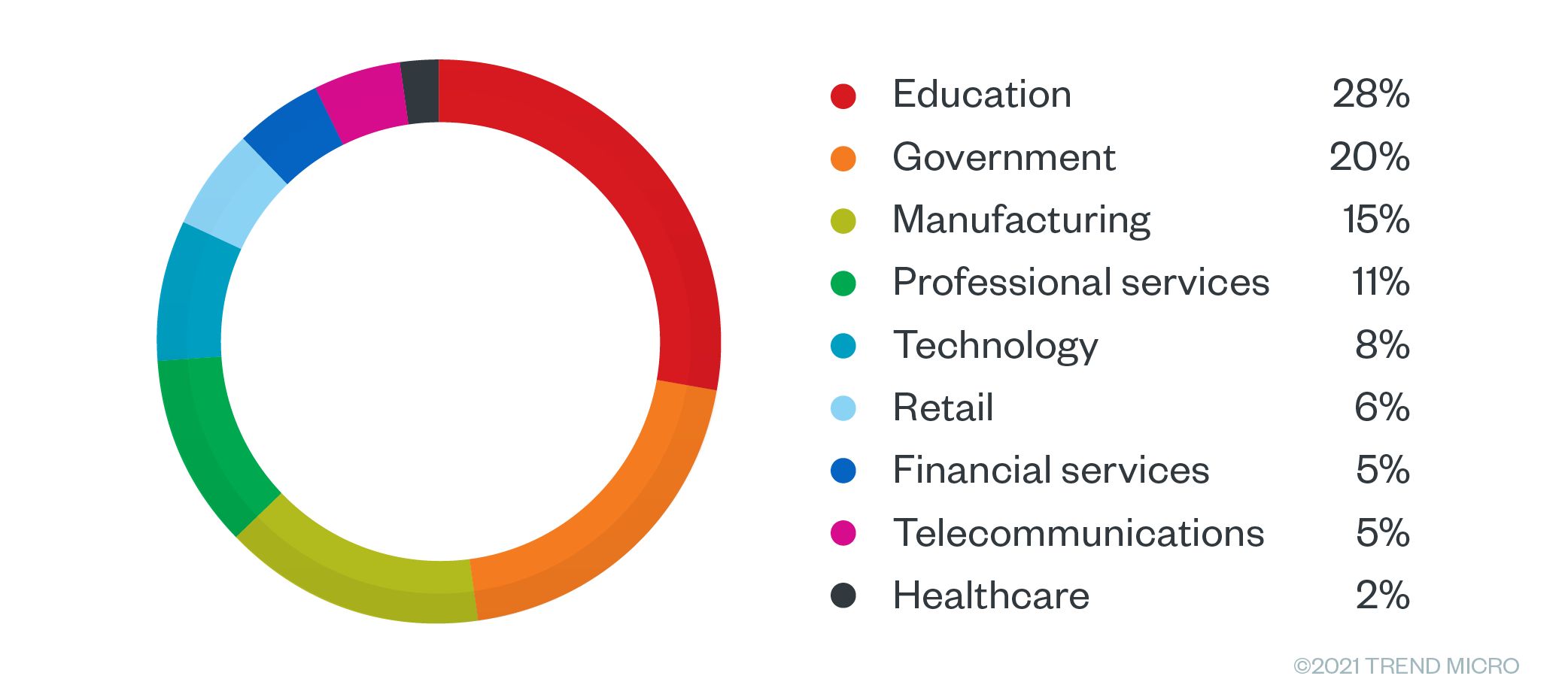

RDP- and VPN-based access was the most common product being offered. After looking at over a thousand advertisements, we noted that 36% offered access to colleges, universities, and K-12 schools, followed by 11% that offered access to manufacturing and professional services.

According to “The State of K-12 Cybersecurity: 2020 Year in Review,” in 2020, the US had a record-breaking number of data breaches targeting the education sector. When the pandemic started, remote learning became mandatory for several months, and many companies were forced to implement work-from-home (WFH) setups with little to no preparation on the security side.

Schools are an ideal target because they present a gold mine of personal information such as financial data, medical records, and Social Security numbers, all of which can be sold on cybercriminal forums or held for ransom. Another possible factor is that schools and universities generally have limited security budgets and they tend to be more open and less tightly controlled than corporations.

Ransomware threats disrupted these industries significantly in 2020 and this was, in no small part, due to access as a service becoming more available in the underground. These ransomware attacks resulted in substantial losses in production and also disrupted operations. In one of the case studies that we examine in this research, we show how access brokers work with ransomware groups to facilitate these attacks.

Figure 12. Sales offerings by industry during the last eight months

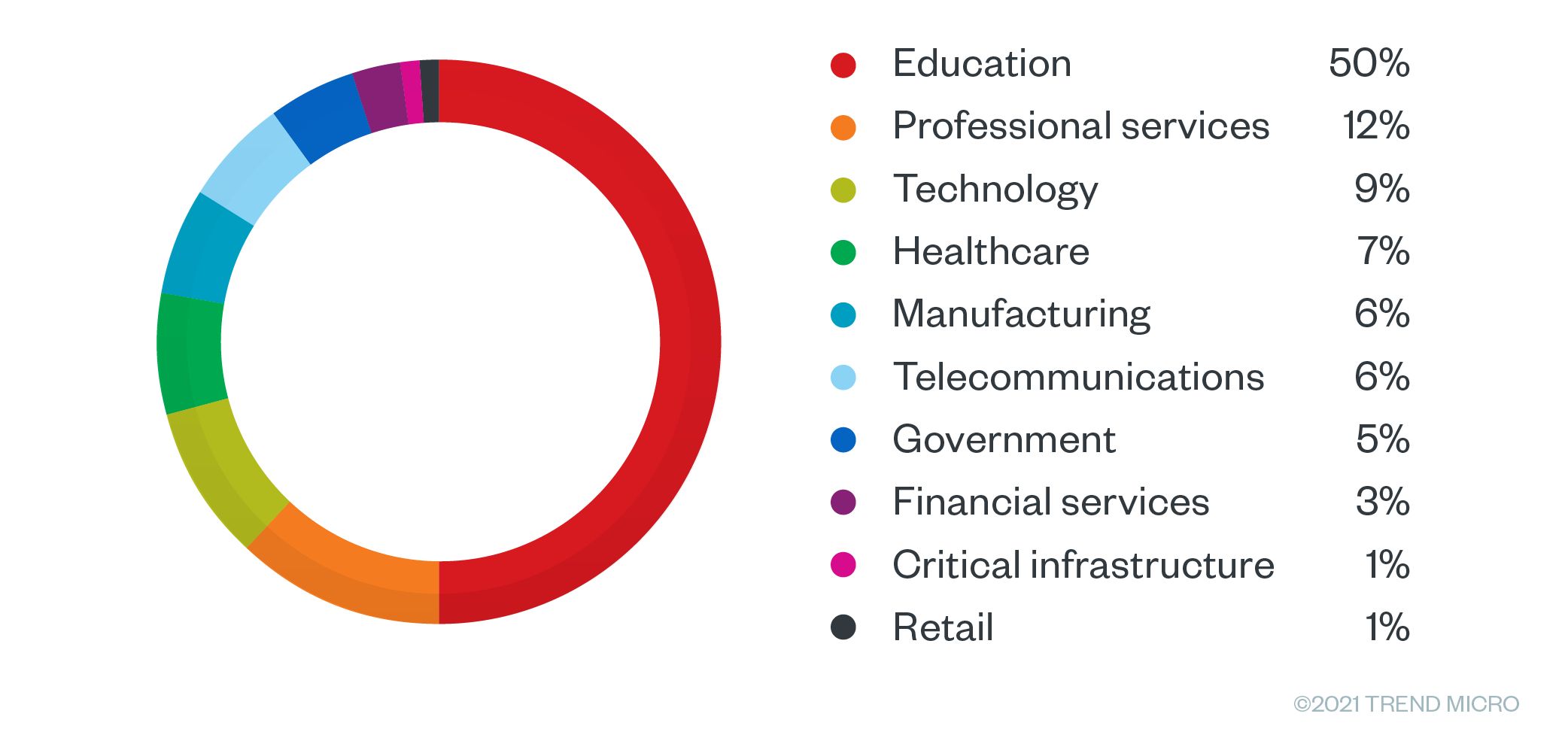

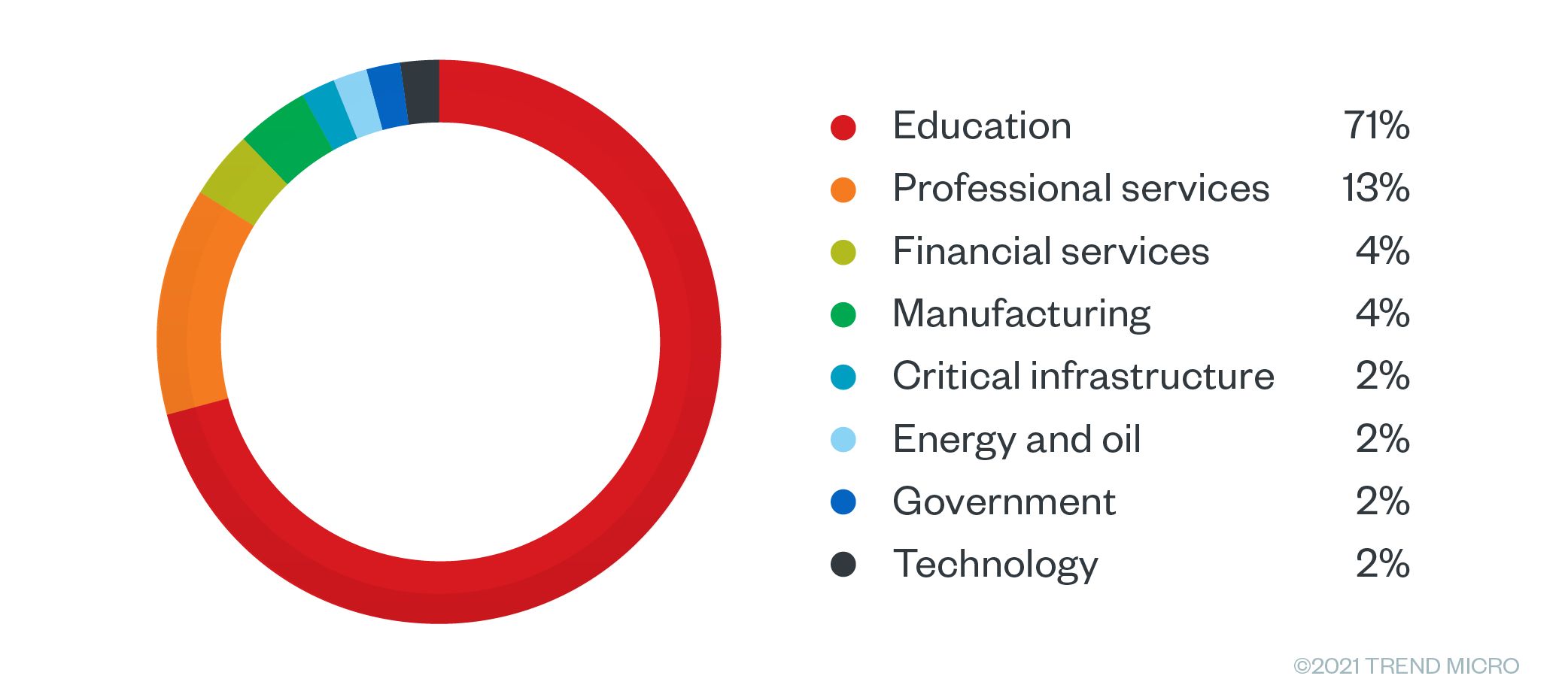

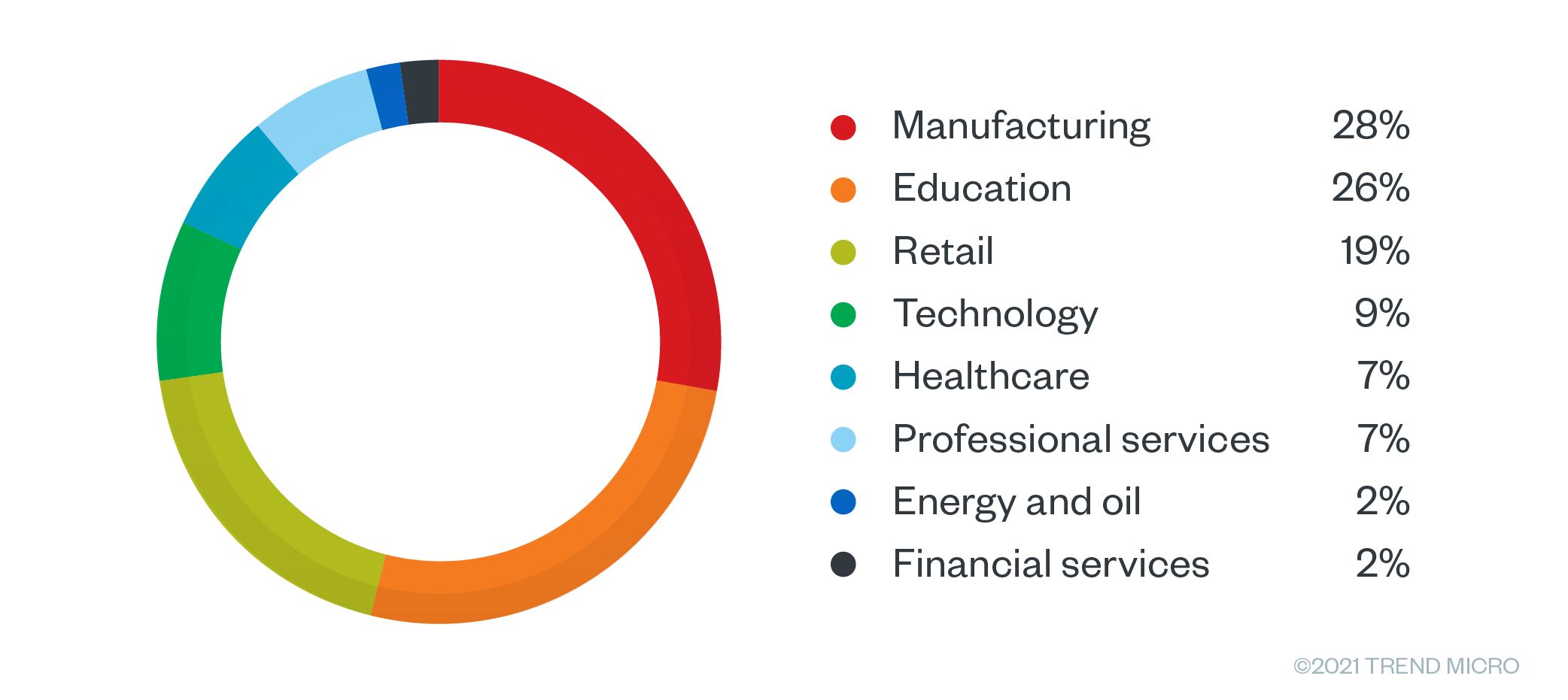

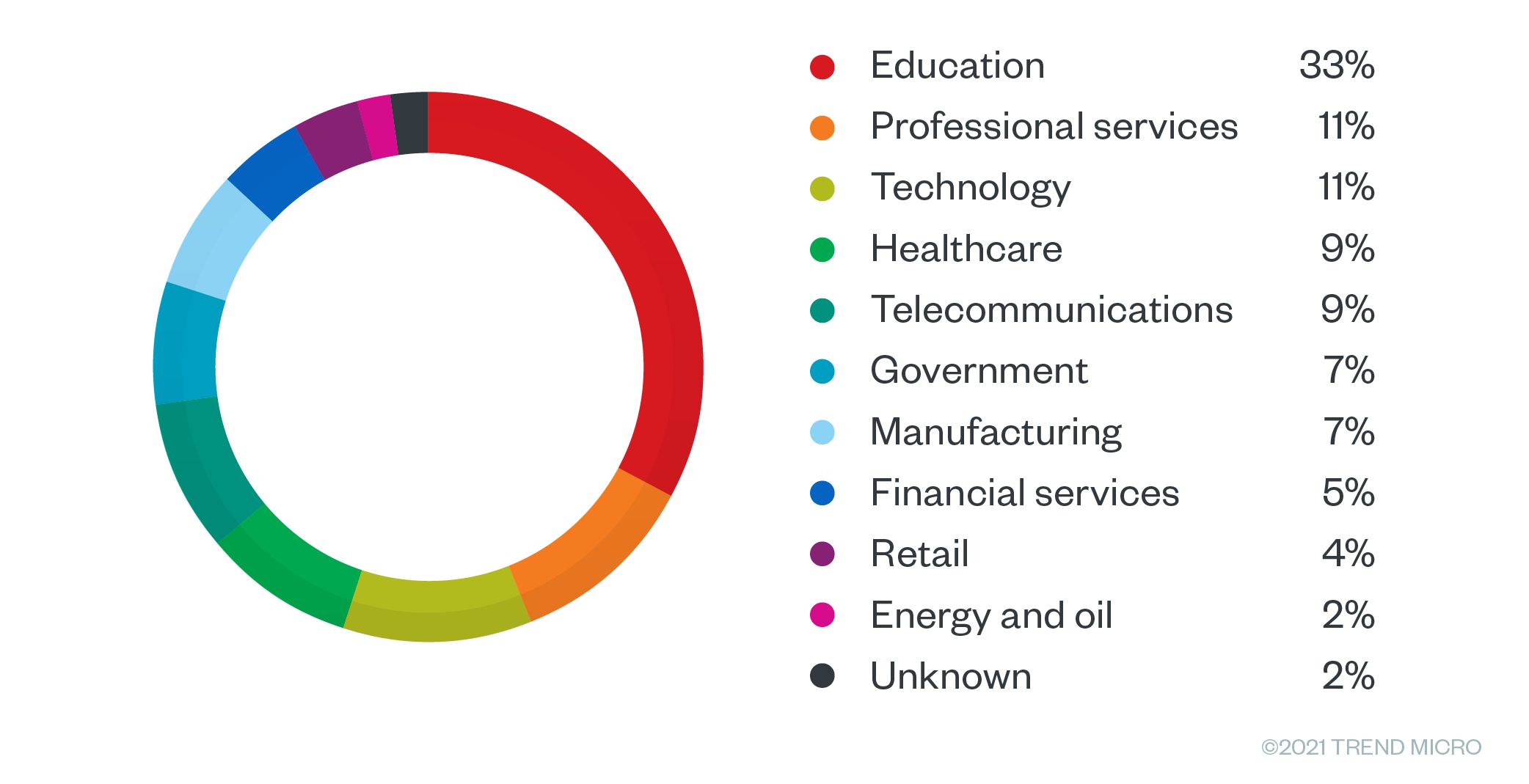

The top affected countries included the United States, Spain, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. For Germany, the top two industries that had access sold in the underground were manufacturing with 28% and education with 26%. Meanwhile, sales offerings for France were largely in the educational sector with 33%. In the USA, 50% of the offerings targeted schools and universities, with professional services following at a distant 12%.

Figure 13. Sales offering by industry for the US

Figure 14. Sales offerings by industry for the UK

Figure 15. Sales offering by industry for Germany

Figure 16. Sales offerings by industry for France

Figure 17. Sales offerings by industry for Spain

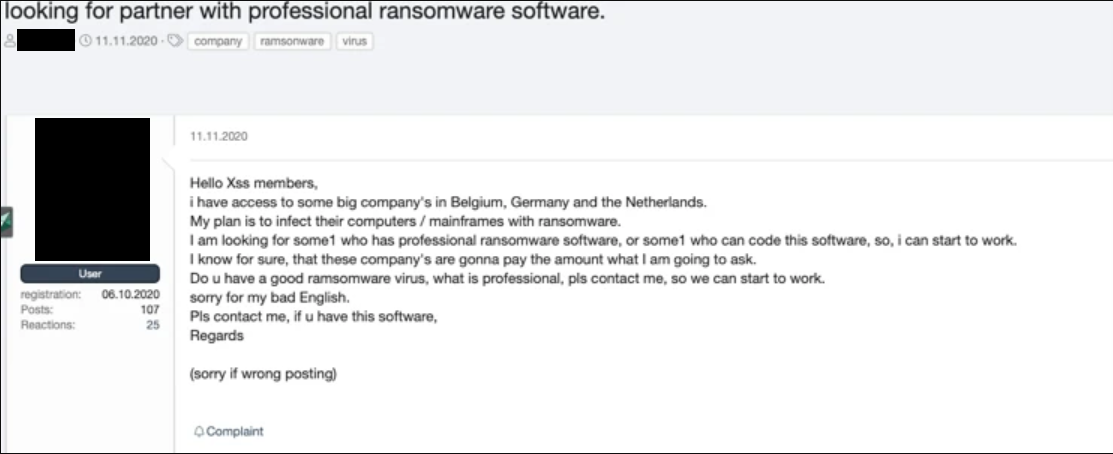

Figure 18. RDP offerings from France, Germany, and UK

Figure 19. A ransomware operator looking for partners after obtaining access to several German companies

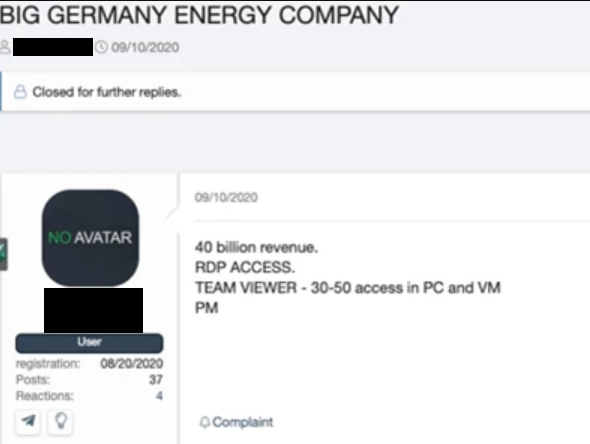

Figure 20. A malicious actor selling access to an energy company located in Germany

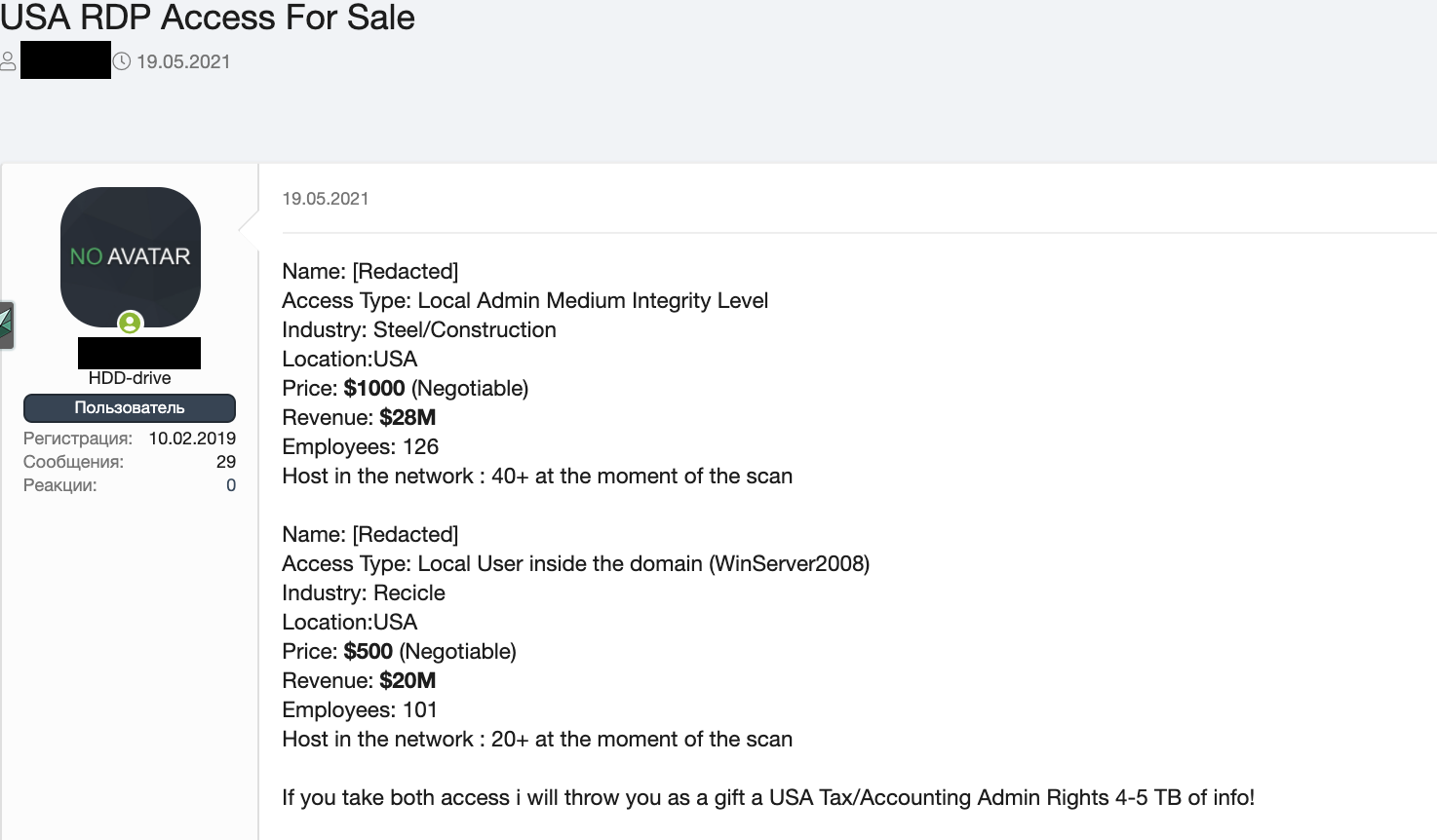

Figure 21. USA RDP access for sale

Prices

In the previous section on RDP and VPN shops, we quoted the prices for access to individual machines as ranging from US$5 to US$10. In this section, we discuss the pricing for access to the systems of whole organizations. These types of offerings typically involve higher levels of access that allow an intruder to gain admittance to more resources, suggesting a level of work that the hacker already performed beforehand in order to allow access. As a result, the prices for these products are higher.

Pricing depends on the following: what the access broker is advertising, the type of access, and the annual revenue of a company. Most dedicated access brokers will not publicly disclose their prices but will advertise the type of company, annual revenue, and access levels instead. Business is always done through private or direct messages.

Annual revenue is important to potential ransomware clients as this would help determine if the victim can afford the ransom. This information is gathered through websites such as ZoomInfo, which provides financial data on companies.

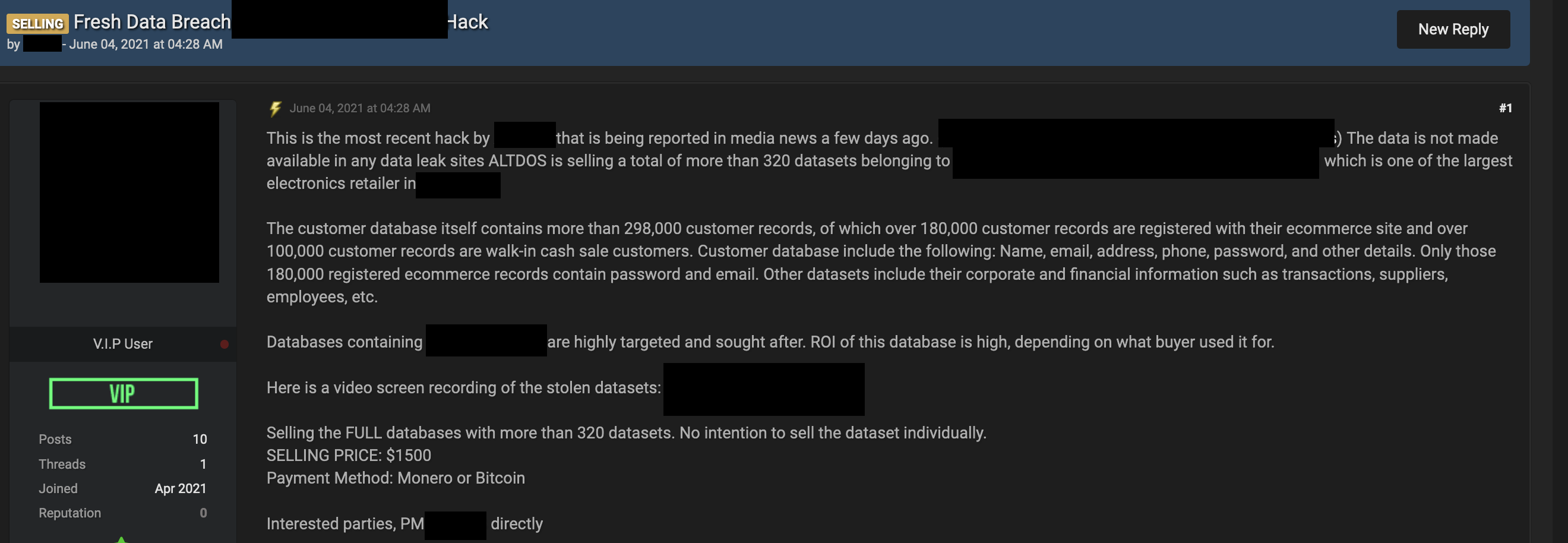

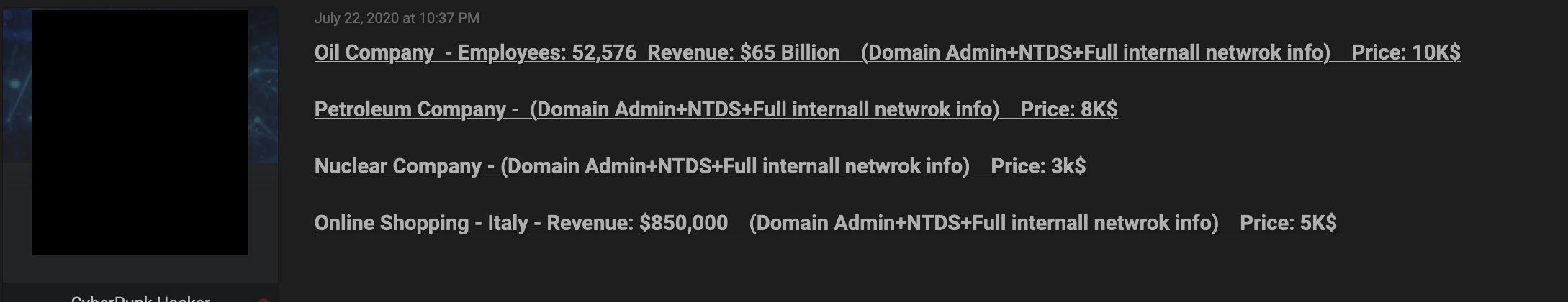

For brokers that do list prices, we found that the average price for access to a business with admin credentials is at US$8,500; however, prices can reach up to US$100,000. It’s worth noting that prices in the upper range can certainly be negotiable. In an English-language forum, we found one example of an offering for access to an oil company with US$64 billion in revenue. The threat actor behind the offering was asking for US$10,000 in exchange for access to the system. Normally, access brokers tend to demand higher prices for access to energy and financial companies, as compared to companies in other businesses, the former garners larger revenue.

As a result, ransomware operators can demand a higher ransom amount from these companies, and threat actors can sell the vast quantities of personally identifiable information (PII) found in the databases of these companies separately, starting at US$200. One example is the data of an electronic audio company in Singapore being sold for US$1,500.

Figure 22. An advertisement for a database of an audio electronics company. The price is advertised at US$1,500.

Figure 23. An advertisement in an English-language form for admin access to oil, nuclear, and petroleum companies. The price ranges from US$3,000 to US$10,000.

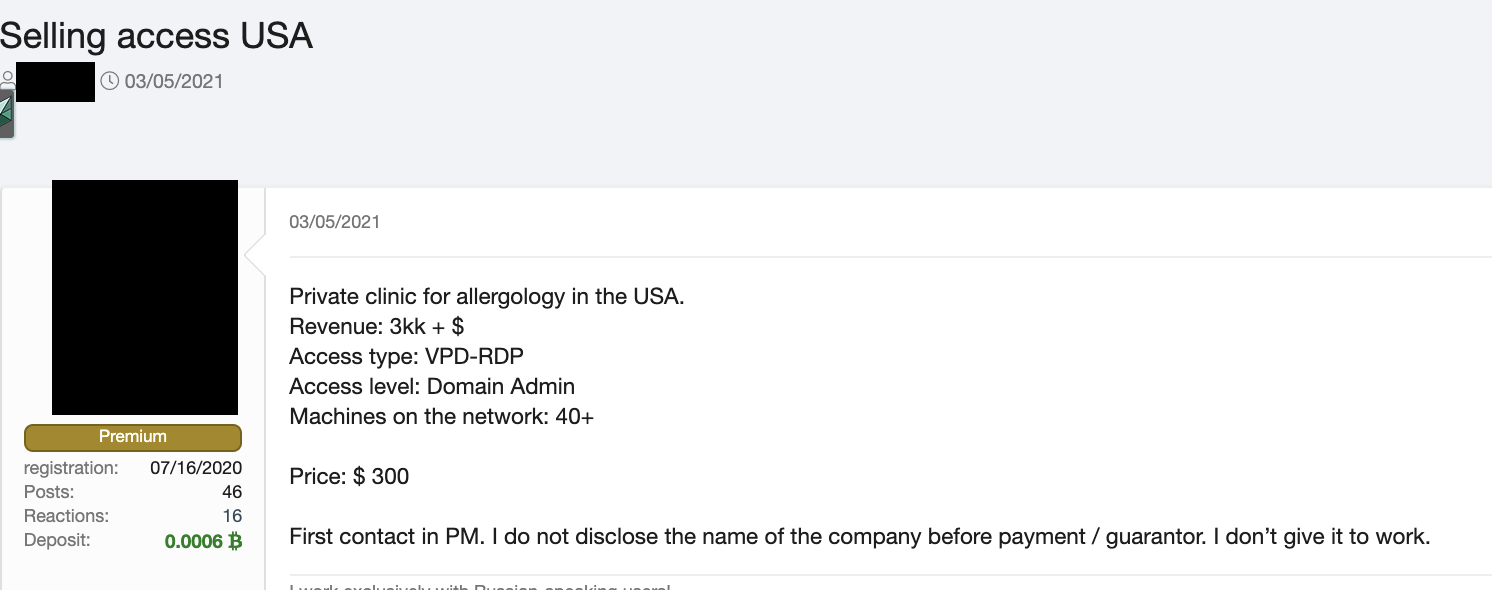

VPN access does not require as much money as admin offerings since the market is flooded with a greater number of VPN choices, which lowers the overall price, especially considering that dedicated VPN shops also exist. One example we found was for access to a US-based clinic that was being sold for US$3,000 on a Russian-language forum. Another entry we saw involved VPN access to a marketing company with revenues of US$27 million a year being peddled for US$800. VPN access to a metal construction company based in Malaysia with a US$5 million annual revenue, on the other hand, was being sold for US$300.

In general, products that allow for an initial foothold into the target company tend to be cheaper than a domain admin or other more powerful ways to access the network. Simply put, the less work a buyer needs to do, the more expensive an offering is.

Figure 24. An advertisement in a Russian-language forum selling access to a US-based clinic

Case studies

In this section, we discuss three case studies that illustrate some of the seller profiles discussed previously. Since these are stories of real companies that have been victimized, we have masked their identities to protect their privacy.

US university – Opportunistic hacker

A US university that ranked among the top 20 in the world was a victim of ransomware by the hacking group FIN11 and the ransomware gang Clop. The former threat actor was responsible for compromising the systems and the latter threat actor was responsible for engaging in extortion. The hackers compromised the system via the vulnerabilities CVE-2021-27101, CVE-2021-27102, CVE-2021-27103, and CVE-2021-27104, then installed a web shell to steal files.

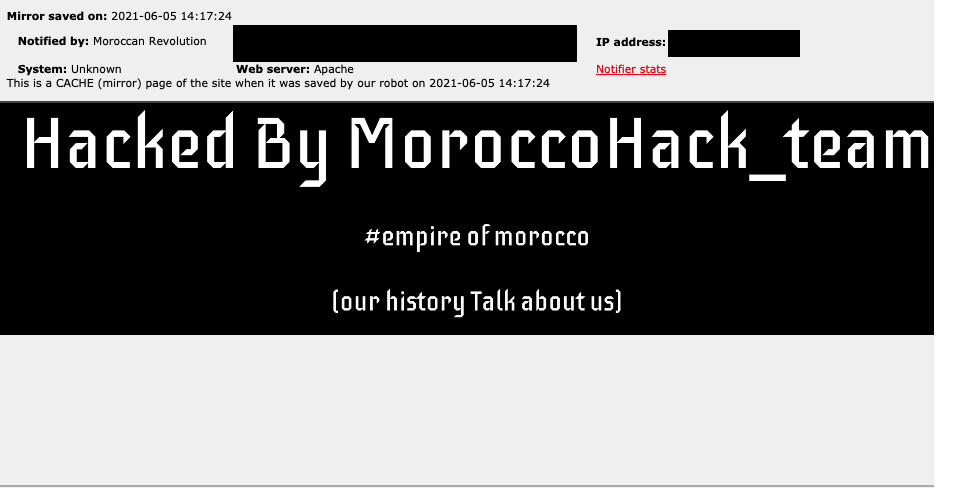

Notably, the university was previously defaced by a hacking group in June 2020, meaning that the network already had unaddressed vulnerabilities. In November 2020, an experienced access broker was selling access to this university via web shell, with the price set at US$950.

Figure 25. The webpage defacement of a US university in June 2020

What makes this hacking and defacement case relevant to this research is that the hacker was seen trying to sell network access to the university network on underground criminal forums. This is a clear example of a one-off seller profile. The network access for sale to online criminals came directly from the malicious actor who was offering the technical details required to have direct access to the network in the form of a web shell installed on one of the university servers.

Figure 26. A forum post showing a malicious actor selling access to a US University in November 2020

The affected university has disclosed that they became a victim of ransomware in April 2021 through a third-party file sharing service. The data obtained by the ransomware group included the names, addresses, email addresses, Social Security numbers, and financial information of students.

XSS ransomware thread analysis – Opportunistic hacker

We found our second case study in a criminal forum. Based on our analysis, it is likely to be true or at least plausible. We studied a thread that detailed an account of a hacker involved in the successful penetration of a Japanese gaming company, as well as how the perpetrator tried to monetize high-privilege access to the network. The incident also involved several major ransomware operators, both directly and indirectly via the hacker’s communication with the groups.

Figure 27. A forum post from a Russian underground forum (translated from Russian)

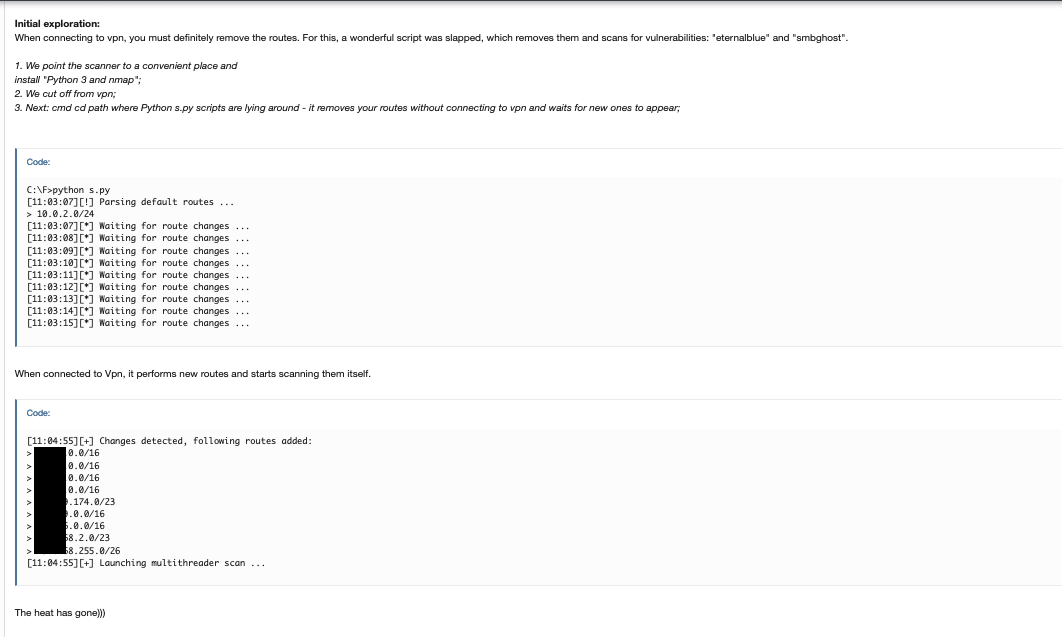

According to the thread, the malicious actor found an exploit, published in 2019, for an older vulnerability, CVE-2018-13379, on GitHub. Upon being contacted by the hacker, the original coder informed the hacker that the gaming company was vulnerable. The hacker then tried the exploit which, to their surprise, worked.

The original article about this thread gives a detailed account of the steps used in the hack, including technical details and mentions of the exact tools used. However, since such information is not relevant here, we will instead move on to discussing the information on monetization.

Once the hacker managed to gain access to the passwords of the domain administrator, it was time to decide on their monetization strategy. To that effect, the hacker got in touch with the LockBit group and asked them to customize the ransom note. Apparently, the hacker didn’t want to use a generic note for such a large target. However, LockBit never replied, so after a week, the hacker started getting in touch with other ransomware groups.

Figure 28. A forum post from a Russian underground forum (translated from Russian)

The first group that the hacker contacted after LockBit to discuss customization of the ransom note was the REvil ransomware group. In their correspondence with REvil, the hacker also mentioned the specific target. Notably, it was also at this time that REvil gave a now-infamous interview in which the threat actor boasted that it was targeting a sizeable “Japanese gaming company.” The hacker did not like this one bit and immediately stopped working with this group.

The hacker then approached Ragnar. According to the hacker, they had never worked this group before. During a friendly chat, the people behind Ragnar offered to help the hacker. They then went ahead with the deal and encrypted the most lucrative data in the gaming company’s servers. However, the hacker claims that the victim never paid because the Japanese government forbade them from doing so.

Figure 29. A forum post from a Russian underground forum (translated from Russian)

At the same time and in a parallel move, the hacker offered two other domains related to the same victim to two other ransomware groups, namely Nefilim and Conti. The hacker showed chat logs of conversations with these two groups; these logs also laid out the conditions for the partnership. In particular, Nefilim provided information on the group’s hacking capabilities and offered the hacker 20% of all ransom payments received. Similarly, the chat log with Conti showed that the group discussed its usual modus operandi to the hacker. This chat log also involved the main Conti penetration tester and mentioned a second penetration tester, as well as an apprentice and a Python programmer.

Unfortunately, we don’t know whether these two side operations were successful or how much money the hacker received, if any. Nonetheless, we did learn about the relationship between hackers and ransomware groups, as well as how access to networks is being sold in the criminal underground, not to mention on what terms. This case study shows an example of a hacker who had a one-off network access to sell and who shopped around for different ransomware groups in order to find the best deal.

This story proves that access as a service is a sellable asset that ransomware operators and other cybercriminals are willing to pay good money for. In addition, this story gave us an opportunity to observe a one-off hacker seller in action and the selling process used in the cybercriminal underground.

It's worth noticing there is a disconnect between the first hack and the subsequent ransomware infection. To be specific, this disconnect happens both with respect to time and modus operandi: After the first successful breach was performed, the hacker took a while to strike deals with ransomware operators. When the second wave of attacks was finally accomplished, some weeks or months had already passed. The people who performed the ransomware attack were completely different from the original hacker, and they probably didn’t even know how the first hack was planned and executed.

Another observation we made when reading stories like this one is that ransomware groups do not really set out to attack one specific company or even one specific industry. Instead, they check the market weekly, similar to how buyers turn up at fishmonger stalls. While ransomware groups do have some parameters, what they end up buying depends on what is being offered. For instance, they might want a company with at least 10,000 seats and US$200 million in revenue, but they’re not too bothered by what type of company they actually end up with. This is similar to a buyer needing enough fish to feed five, regardless of the kind of fish they ultimately purchase.

Figure 30. A forum post from a Russian underground forum (translated from Russian)

Bulk access seller – Dedicated access broker

TThe third case study involves a prolific network access seller. In our monitoring of the cybercriminal underground, we came across this seller’s offerings and were surprised at the number of accesses for sale, as well as the kinds of companies being offered.

Certain access brokers specialize in specific areas, while others offer as many assets as they can possibly get their hands on. This is the story of one such “bulk seller.” The amount of network accesses that this seller offers at any one time is staggering, with a variety of networks both far and wide, as well as both in terms of industries and geographical locations.

During our research, we were able to collect a list of almost 800 servers that had been compromised. Access to these servers was also being sold. We compiled this list over months of following this seller’s online forum posts.

Companies tend to name their servers by the functions they fulfill in the network. For example, web servers are usually named “www.” We discovered an interesting part of our list when we sorted these networks by the name of the compromised server. In the sorted list, we were able to see dozens of servers from all over the world named “citrix.” We might assume that many of these servers have been compromised with the same vulnerability, or at least a similar one. However, while this is a possibility, we cannot know for sure.

Figure 31. Location of servers that the malicious actor is selling access to. The US accounts for the majority, followed by the UK, Spain, France, Germany, and Italy.

In the same vein, there are many servers on this list named “ctx,” “remote,” or “desktop.” Other server names for sale strongly reminded us of the concept of remote access. We also observed servers named “vpn,” “sslvpn,” “desktop,” “portal,” “virtuallab,” and “remoteus,” for example. An even stronger possibility is that these servers came from malware logs that this seller mighthave previously purchased from botnet operators and other cybercriminals. This is reinforced by the fact that many of these servers are named using keywords that suggest they are entry gateways for users, meaning that these seem to be the servers that users need to connect to in order to enter their credentials and access a corporate network.

We have been seeing this particular access broker since early 2020 on cybercriminal forums selling network access. We have also examined some of their previous activities and we were able to see that on another (now offline) criminal forum, they publicly admitted to buying malware logs from criminal underground repositories. This seller also shared how they validate the credentials found in these logs via certain underground tools, including some that the seller wrote themselves.

According to our research, the most likely scenario is that by purchasing malware logs, this criminal has been able to collect user login attempts to a large number of VPN networks around the world. This access broker then tries to log in to check if the credentials are valid and then sells them as “network accesses” on criminal forums.

In order to do this at scale, they seem to have automated tools that parse the logs, as well as other tools to validate credentials. These consist of both self-developed tools and tools that are purchased from the criminal underground. The seller also researches the networks that these credentials belong to, in order to advertise them more appropriately to potential clients.

To advertise their network accesses, this actor offers them on cybercriminal forums where the seller engages potential customers and closes the deal, normally via private message.

Ransomware and access as a service

Even though ransomware is not the only criminal payload that follows an intrusion, it is probably the most common one and the one most readers are likely concerned about. We elaborate on other payloads in our research, “The Life Cycle of a Compromised (Cloud) Server.”

Most of the time, it is access brokers who bear the burden of the network breach that allows a ransomware attack to succeed. Even though ransomware still has by far the most visible impact during such a breach, the enablers of those attacks are usually the ones that quietly break and then sell access to other malicious actors.

Usually, profits from ransom payments tend to be divided into 80% for the ransomware group and 20% for whoever provided them the way in. We estimate that most of the time, ransomware attacks succeed because someone provided the ransomware group access to the target network, whether this someone is an access seller or a single hacker, as in the case study we previously discussed.

On a side note, in the affiliate model, the splits are reversed: The ransomware group receives 20%, and the affiliate receives 80%. In this model, the affiliates are expected to do the ransom negotiation; therefore, the payout is higher for them. Obviously, ransomware groups prefer the current access model that is becoming prevalent in the cybercriminal underground.

Because the ransomware payload is the most visible part of the attack, defenders tend to focus primarily on this. Consequently, most security discussions focus on ransomware attacks instead of on monitoring and mitigating the actions of access brokers. The same can be said regarding the media attention that ransomware groups regularly garner in contrast to access brokers.

| Ransomware | Access broker | |

| Profits (%total) | 80% | 20% |

| Media attention | 100% | 0% |

| Visibility to victim | 90% | 10% |

| Responsibility over attack | 20% | 80% |

Figure 32. An estimate of the division between ransomware groups and access brokers for profits, media attention, visibility to the victim, and responsibility over the attack

Recommended defense strategies

Defenders have typically focused their attention on preventing and mitigating the effects that attackers have on their networks, with ransomware having quite a large consideration. Although usually, security best practices such as having effective backup capabilities, monitoring mass-encryption attempts, monitoring malicious emails, and shielding users from their effects are excellent preventive measures, network defenders are not limited to these steps.

In this section, we propose additional steps that cybersecurity staff and network defenders can take in order to counteract the changes in attacker behavior we have previously outlined. These are all aimed at detecting and preventing the initial breach that allows a subsequent ransomware attack.

- First, monitor for public breaches (if you are not doing so already). This means looking at password breaches whenever they are made public. In addition, it would be helpful to monitor the criminal underground, and to regularly look for signs of a breach on your network. Any offer of access to your network should immediately raise red flags. If you do not have resources to do this monitoring yourself, consider purchasing such a service from a dedicated security provider.

- If you suspect that some of your credentials are out in the open, trigger a password reset for all your users. Consider resetting the credentials of your system and service accounts as well.

- Strongly consider setting up a two-factor authentication (2FA) system for your remote users, if you have not yet done so. This will go a long way toward preventing attackers from accessing your network via leaked credentials.

- After an attack, allow your incident response (IR) team to factor in the very common multi-attacker scenario that we explained previously. Modern attacks happen in two or more stages, where the initial attackers are responsible for setting up and maintaining external access, after which they will sell the access to other threat actors who will perform the real attack. These separate attack points are different with respect to their timing and modi operandi. Keeping this in mind can change the way IR teams set up their investigations.

- Monitor user behavior by looking for things that users should not be doing. Credential dumping, network scanning, and other unusual activities should raise red flags that any Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) or managed detection and response (MDR) product should be able to pick up. Monitor your SIEM/MDR logs and set alerts. If you do not have these kinds of products, consider acquiring them in order to increase your visibility across the network.

- Keep a watchful eye on your DMZ. Assume that your internet-facing services (VPN, webmail, web servers, among others) are under constant attack in a hostile environment. These are the most important machines to keep fully patched. Regularly rotate passwords, keep installations to an absolute minimum, and enable 2FA. Also, it is safer to assume that these machines are compromised at all times and that, therefore, all inbound connections from them are also potentially malicious.

- Implement network segmentation and microsegmentation to hinder lateral movement and support security monitoring. Organizations can benefit from segmenting office and server networks to effectively limit an attacker’s scope of compromise. This can be done by microsegmenting information systems, using properly defended management networks to protect underlying administrative interfaces on network infrastructure, and employing virtualization and cloud infrastructures.

- Consider using standard best practices on password policies. Organizations such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the US and the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) in Europe have updated guidelines on this topic that are worth looking at, if you haven’t already. In particular, we recommend their collection of updated password guidelines as compiled on GitHub.

- If you are especially cautious, assume your users have already lost their passwords to criminals and therefore, you have been breached already and are always exposed. This would then force you to implement a form of zero trust architecture and security posture across your network.

Conclusion

The criminal underground is a dynamic marketplace where the attackers usually acquire the resources to put into practice their criminal business plans and operations. Criminals can buy or license their malware of choice, hire experts to disseminate it, and ultimately profit by selling whatever the attack produced — and typically, attacks produce stolen data.

Until recently, it was common for skilled attackers to buy exploits or vulnerabilities in the criminal underground to try and enter corporate networks. Nowadays, access as a service offerings have simplified attackers’ lives by selling direct access to target networks. This allows attackers to get straight in and allows them to focus more on lateral movement and privilege escalation. Attackers can now spend more time inside the network finding the servers that hold the most interesting data.

Ultimately, the final result is that attacks get into the network sooner and more easily but develop across a longer timeframe. More importantly, this change in attacker behavior needs to be considered when defenders plan their strategy. Monitoring the network for signs of intrusion should focus both on vulnerabilities at the perimeter and on users trying to move laterally within the network and trying to gain increased access to resources. A good defense strategy needs a holistic solution that can look at these two aspects while also factoring in the extended timeframe needed when looking at SIEM and MDR software logs.

Defenders have a finite number of resources at their disposal, and they need to invest those resources in the most efficient security solutions. We suggest that defenders monitor and prevent illegitimate access to their networks as a viable, effective, and in some ways, more reliable. method of stopping ransomware and other attacks.

Key findings:

- Access as a service is a recent and more professionalized criminal business model that is based on selling access to networks. From a cybercriminal’s perspective, buying access to a network requires less trust and is cheaper than buying an exploit.

- The access as a service market is rising in prominence while the exploit market is shrinking and becoming more specialized. We elaborate on this topic in our paper, “The Rise and Imminent Fall of the N-Day Exploit Market in the Cybercriminal Underground.”

- If a company can protect themselves from credential theft, they’d be in a much better position to defend themselves against any future breaches.

- The consequences of this shift in attacker behavior cannot be ignored. Adjusting our defenses is key if we want to be successful at keeping these new attackers at bay.

Like it? Add this infographic to your site:

1. Click on the box below. 2. Press Ctrl+A to select all. 3. Press Ctrl+C to copy. 4. Paste the code into your page (Ctrl+V).

Image will appear the same size as you see above.

Recent Posts

- The Next Phase of Cybercrime: Agentic AI and the Shift to Autonomous Criminal Operations

- Reimagining Fraud Operations: The Rise of AI-Powered Scam Assembly Lines

- The Devil Reviews Xanthorox: A Criminal-Focused Analysis of the Latest Malicious LLM Offering

- AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization

- Agentic Edge AI: Development Tools and Workflows

Complexity and Visibility Gaps in Power Automate

Complexity and Visibility Gaps in Power Automate AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization

AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization The AI-fication of Cyberthreats: Trend Micro Security Predictions for 2026

The AI-fication of Cyberthreats: Trend Micro Security Predictions for 2026 Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One

Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One