There are many online stories and blog posts teaching people how to make “passive income” by sharing spare computing power and/or unused internet bandwidth. When users willingly or unwillingly install such software on their computers, the systems become agents of a distributed network. The operators of this distributed network might monetize it by selling proxy services to their paying customers.

Even though the websites hosting the “passive income” software emphasize legitimate use cases, we have found that such software can pose security risks to the downloaders. This is because some paying customers of these proxy services may be using them for unethical or even illegal purposes.

In this investigation, we have studied several prominent “passive income” applications, which turn the computers running them into residential IP proxies, and those proxies are sold to clients to use as “residential IP proxies.” The apps are often promoted via referral programs, with many famous YouTubers and bloggers promoting them.

We also investigated questionable developers who bundle “passive income” apps with third party libraries. This means that the downloaders do not know about the “passive income” apps, and the income actually goes to the developers. The users are exposed to disproportionate risks, since they cannot control the activities performed using their home/mobile IP addresses.

Make easy money online just by sharing unused bandwidth?

There are many posts in public blogs and YouTube channels teaching people how to make “passive income” with easy step-by-step tutorials. The authors of these tutorials often make money through referrals and promote several “passive income” applications in parallel.

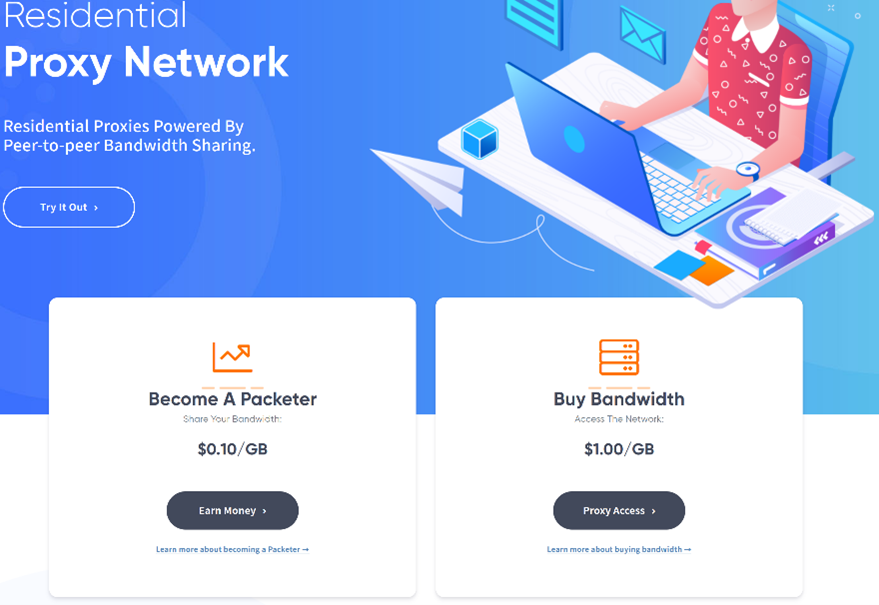

Some examples of companies using the “network bandwidth sharing” monetization scheme include HoneyGain, TraffMonitizer, Peer2Profit, PacketStream, and IPRoyal Pawns, among others. These companies offer users a way to passively make money online by downloading and running their software agent. Typically, users will share their connection and get credits, which can later be converted into actual money.

Income-seekers will download the software to share their bandwidth and make money, but the companies sell the bandwidth to customers who want residential proxy services. The company websites list a few reasons that someone may need proxy services: demographic research, bypassing geographic restrictions for gaming and bargain hunting, or privacy reasons, to name a few.

These companies can be found easily. A simple search for “passive income unused bandwidth” on Google immediately yields names such as IPRoyal Pawns, Honeygain, PacketStream, Peer2Profit, EarnApp, and Traffmonetizer. Some people on internet forums and discussion boards even suggest installing multiple applications at the same time to make more money, or run multiple VMs to increase the potential profits.

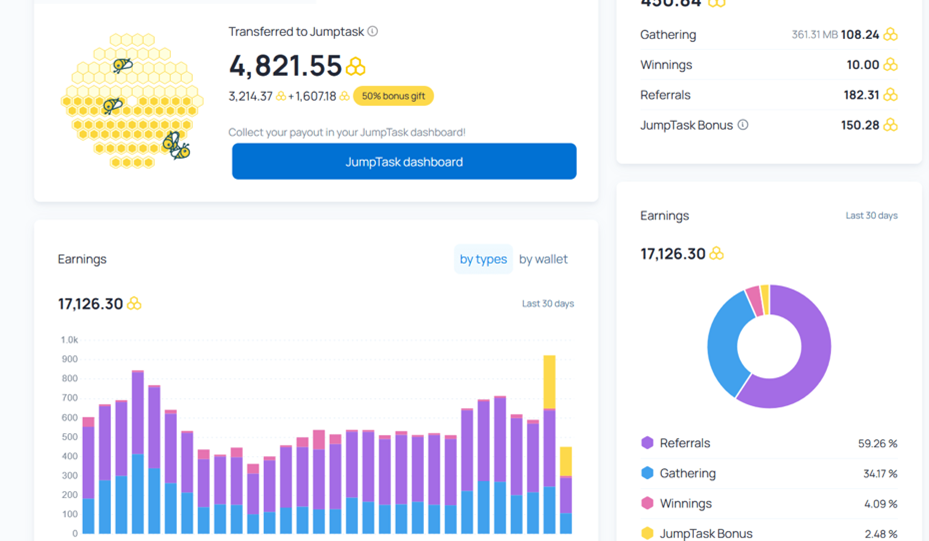

Shared bandwidth may not even earn the biggest cut of passive income that average users are making. According to a dashboard shared by a blogger, referrals make an even bigger portion (more than 50% in this chart) of the blogger’s income.

Even with the prominent figures shown on the chart, however, the blogger claimed he made around US$20 per month. But users are not guaranteed to receive even this low level of revenue on a regular basis, or at all. And, in exchange for this uncertain income, users are being asked to regularly accept unknown levels of risk.

What really happens?

These “network bandwidth sharing” services claim that the users’ internet connection will mainly be used for marketing research or other similar activities. Therefore, people who share their internet connection are making money online while also helping the “industry”.

But is this true? To examine and understand the kind of risks a potential user might be exposed to by joining such programs, we recorded and analyzed network traffic from a large number of exit nodes of several different network bandwidth sharing services (exit nodes are computers who had these network bandwidth sharing services installed).

From January to September 2022, we recorded traffic coming from exit nodes of some of these passive income companies and examined the nature of the traffic being funneled through the exit nodes.

First of all, our observation confirmed that traffic from other app partners are funneled to our exit node and most of it is legitimate. We saw normal traffic, such as browsing news websites, listening to news streams, or even browsing online shopping websites. However, we also identified some questionable connections. These connections demonstrated that some users were performing activities that are suspicious or possibly illegal in some countries.

A summary of suspicious activities is given in the following table. We organized these activities by similarity and noted the proxy networks where we have observed these activities.

| Suspicious activity | Traffic from Proxyware Applications |

| Access to 3rd-party SMS and SMS PVA services | Honeygain, PacketStream |

| Accessing potential click-fraud or silent advertisement sites | Honeygain |

| SQL injection probing | Honeygain, PacketStream, IPRoyal Pawns |

| Attempts to access /etc/passwd and other security scans | Honeygain, PacketStream |

| Crawling government websites | Honeygain |

| Crawling of personally identifiable information (including national IDs and SSN) | IPRoyal Pawns |

| Bulk registration of social media accounts | IPRoyal Pawns |

In most cases, the application publishers probably would not be legally responsible for suspicious or malicious activities by the third-parties who use their proxy services. However, those who installed the “network bandwidth sharing” applications have no means of controlling or even monitoring what kind of traffic goes via their exit node. Therefore, these network sharing apps are classified as riskware applications that we call proxyware.

Suspicious activities from proxyware

The table above outlines the malicious and suspicious activity we observed, and we go into further detail about these activities in this section.

We observed multiple instances of automated access to third-party SMS PVA providers. What are SMS PVA services? We have written a paper about SMS PVA services and how they are often being (mis)used. In a nutshell, these services are often used for bulk registration of accounts in online services. Why do people often use them in combination with proxies? Those accounts are often bound to a particular geographical location or a region, and the location or a region has to match the phone number that is being used in the registration process. Thus, the users of SMS PVA services want their exit IP address to match the locality of the number, and sometimes use a specific service (in case a service is only accessible in a particular region).

These bulk registered accounts (aided by residential proxies and SMS PVA services) are often then used in a variety of dubious operations: social engineering and scams against individual users, and abuse of sign-up and promotion campaigns of various online businesses that could result in thousands of dollars in monetary loss.

Potential click fraud was another type of activity that we observed coming from these networks. Doing click-fraud or silent ad sites means that the computers with “passive income” software are used as exit nodes to “click” on advertisements in the background. Advertisers have to pay for ineffective clicks (no one really saw the ads) and the network traffic looks almost identical to a normal user clicking on the ads at home.

SQL injection is a common security scan that attempts to exploit user input validation vulnerabilities in order to dump, delete, or modify the content of a database. There are a number of tools that automate this task. However, doing security scanning without proper authorization and doing SQL injection scans without a written permission from the website owner is criminal activity in many countries and may result in prosecution. We have observed a number of attempts to probe for SQL injection vulnerabilities from many “passive income” software. This kind of traffic is risky and users who share their connections could potentially be involved in legal investigations.

Another similar set of activities with similar risks that we observed is scans from tools. These scans attempt to access the /etc/passwd file by trying to exploit various vulnerabilities — when successful, this signifies that a system is vulnerable to arbitrary file exposure and allows an attacker to obtain the password file on a server. Hackers use such software vulnerabilities to retrieve arbitrary files from vulnerable websites. Needless to say, it is illegal to conduct such activities without written permission from the server’s owner.

Crawling government websites might not be illegal at all. There usually are terms of fair use requiring that users not place too many queries at the same time. Many websites use technical means to prevent heavy crawling by using captcha services. We have observed the use of automated tools that use anti-captcha tools to bypass these restrictions while trying to access government websites. We have also seen crawlers that scrape for legal documents from law firms and court websites.

Crawling of personal identifiable information (PII) might not be illegal in all countries, but this activity is questionable because we do not know how such information may be later misused. In our study, we have seen a suspicious crawler downloading information of Brazilian citizens in bulk. Such information included names, dates of birth, gender and CPF (equivalent to national SSN). Obviously, if such activity is investigated, the “passive income” software users would be the first point of contact, as it would be their IP address that got logged on those websites.

People who register a lot of social media accounts can use it for multiple purposes, such as online spam, scam campaigns, and bots that spread misinformation and promote fake news. Such accounts are also often used to give fake reviews of goods and services. In the collected traffic, we have seen the registration of TikTok accounts with unconventional email addresses. Even though it is not illegal per se, users who have installed “passive income” software might be asked to prove who they are or to get through more “validate you are a human” tests in their normal browsing activity. This is because there are too many registered accounts from their home IP and they can be misidentified as being affiliated with those campaigns.

If you think these examples are farfetched, there is a case in 2017 when a Russian citizen was arrested and accused of terrorism. This person was running a Tor exit node and someone used this to post pro-violence messages during anti-government protests. Proxyware is similar to a Tor exit node because both funnel traffic from one user to another. This example specifically shows how much trouble you can get yourself into if you don’t know what the people using your computer as an exit node are doing.

Other variants of proxyware run without user consent

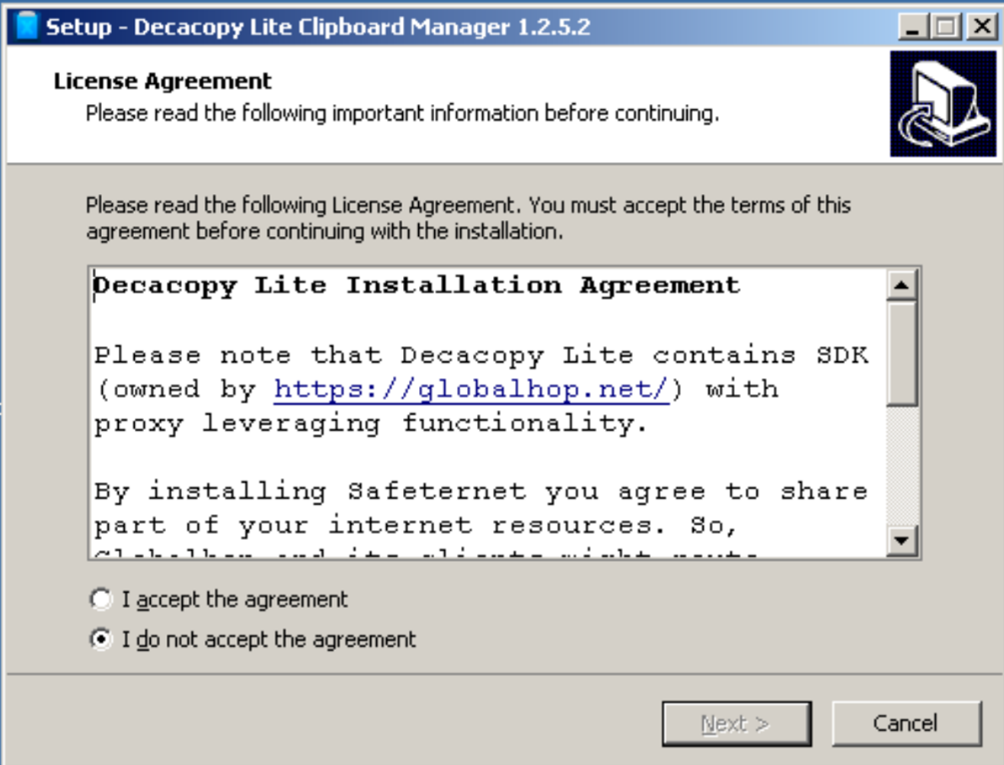

During our research, we also identified a group of unwanted applications that are distributed as free software tools. However, it appears to us that these applications are covertly turning the user machine into a proxy node. These applications appear to install Proxyware functionality on devices, like Globalhop SDK, without clearly notifying users that their devices will be used as passive exit nodes. Some end-user license agreement (EULA) documents may explicitly mention the inclusion of Globalhop SDK or the exit node functionality of the apps, while others do not. But, in our opinion, including notification only in the EULA—a document that few users ever read—doesn’t provide fair notice to users that installing the app will result in unknown third parties using their devices as an exit node.

In either case, such software still brings risks to their users, and the “passive income” is only paid to the app developers. The software users may only enjoy the free software itself without the “passive income.” Examples of such software include:

- Walliant, an automated wallpaper changer

- Decacopy Clipboard Manager, a program designed to store users’ recent copy-pasted content

- EasyAsVPN, unwanted software often installed by tricking users

- Taskbar System, an app that changes the color of your taskbar

- Relevant Knowledge, an adware

- RestMinder, a clock software that reminds users to take a rest

- Viewndow, software that keeps selected app window pinned

- Saferternet, DNS based web-filtering software

The network traffic produced from these proxy networks is similar to the traffic produced by “passive income” software, as both types of software serve as exit nodes for their providers. We have observed the following malicious / debatable activities.

| Malicious / Debatable Activity | Traffic from “Passive Income” Applications |

| Registering “NFT lucky draw” | Walliant, Decacopy Clipboard Manager, Taskbar System |

| SQL injection and scans | EasyAsVPN, Decacopy Clipboard Manager, Walliant |

| Crawling government websites | Walliant, Restminder, Taskbar System, Decacopy Clipboard Manager, Relevant Knowledge |

The IOC and traffic patterns are listed in the appendix.

Conclusion

In this article, we have described how popular “passive income” software advertised as “network bandwidth sharing” uses the residential IP of their install base as exit nodes, and the risks that the malicious and dubious network traffic might bring to the users.

By allowing anonymous persons to use your computer as an exit node, you bear the brunt of the risk if they perform illegal, abusive, or attack related actions. This is why we don’t recommend participating in such schemes.

“Passive income” providers might have ethical policies in place, but we have seen no evidence of these providers policing the traffic being routed into the exit nodes. If they do, then the very obvious SQL injection traffic we’ve seen should have been filtered out. If these providers wish to improve their policies, we suggest that they be more upfront and make it clear to the software users that they do not control what their customers do (and therefore do not have full visibility over the traffic to the exit node).

There are measures to ensure attacks and abuse are limited — such as strict implementation of traffic scanning, testing of certificates, and other techniques — but enforcement of these policies is key. Some of the app publishers that we’ve contacted about these concerns have responded that they protect their users through their know-your-customer (KYC) practices for their app partners. This offers some protection against misuse of devices employed as exit nodes, however, there are still reasons to be concerned. These policies can be falsified, or customers can find ways to circumvent them.

All in all, potential users of these apps, especially with the current implementation of proxyware services, need to be aware that they are exposing themselves to unknown levels of risk in exchange for an uncertain and likely unstable amount of potential “passive income”. Here are some security measures for protection against the risks listed above:

- Understand the risks of “passive income” software and consider removing them from laptop, desktop, and mobile devices.

- Company IT staff are suggested to inspect and remove “passive income” software from company computers.

- Install Trend Micro protection suites, as Trend Micro has listed the applications listed in this article as Riskware. These products also stop the “passive income” apps from downloading malicious applications.

For people who want to learn more about “passive income” apps or proxyware, we recommend this article from CISCO Talos and Resident Evil: Understanding Residential IP Proxy as a Dark Service.

Appendix

Traffic patterns of malicious/suspicious activities

The following table shows some of the traffic patterns of malicious/suspicious activities forwarded by the “passive income” applications that we have observed. SOC staff may want to add the patterns to their watchlist. (dddd denotes to anonymized digits, xxxx to anonymized strings.)

| Activity | Traffic Patterns |

| SQL injection | domain/component/fireboard/?%3C%21func=view%20%20UNION%20ALL%20SELECT%20NULL%2D%2D%20%2D&catid=d&id=ddddd&start=ddd

/?action=/etc/passwd&board=/etc/passwd&cat=/etc/passwd&conf=/etc/passwd&content=/etc/passwd&date=/etc/passwd&detail=/etc/passwd&dir=/etc/passwd&doc=/etc/passwd&document=/etc/passwd&download=/etc/passwd... |

| /etc/passwd hack | ... FROM%20information_schema.tables%20WHERE%202%3E1--/**/;%20EXEC%20xp_cmdshell(%27cat%20../../../etc/passwd%27)%23... |

| Bulk register social media accounts | tiktokv.com/passport/email/register/v6/?aid=ddddd&email=...@gmail.com&password=...&rre=1&rrv=1&as=a1iosdfgh&cp=androide1 |

IOC of “Passive Income” applications

The following IOCs have been listed by Trend Micro solutions as “probably unwanted applications” (PUA). Since there are more than 842 IOCs, we are only listing the most frequent ones here.