One million.

In 2012, we predicted that the number of malicious and high-risk Android™ apps would reach 1 million by the end of 2013. Unsurprisingly, our prediction came true with three months to spare. Considering that the first Android malware came out in 2010 and that it took them only three years to reach the 1-million mark highlight the extremely rapid pace cybercriminals churn out malicious and high-risk apps.

2013 also showed that the mobile threat landscape is slowly moving beyond apps. We saw infection and attack chains that didn’t solely rely on malicious app installation. We also saw mobile ads promote fake sites and scams. Bad guys also used spear-phishing emails and PC malware to spread mobile malware. Even the malicious apps changed. Apart from app stores, vulnerabilities increasingly became a launchpad for app installation and modification. If anything, the 2013 mobile threat landscape proved just how many tools cybercriminals had in their arsenal.

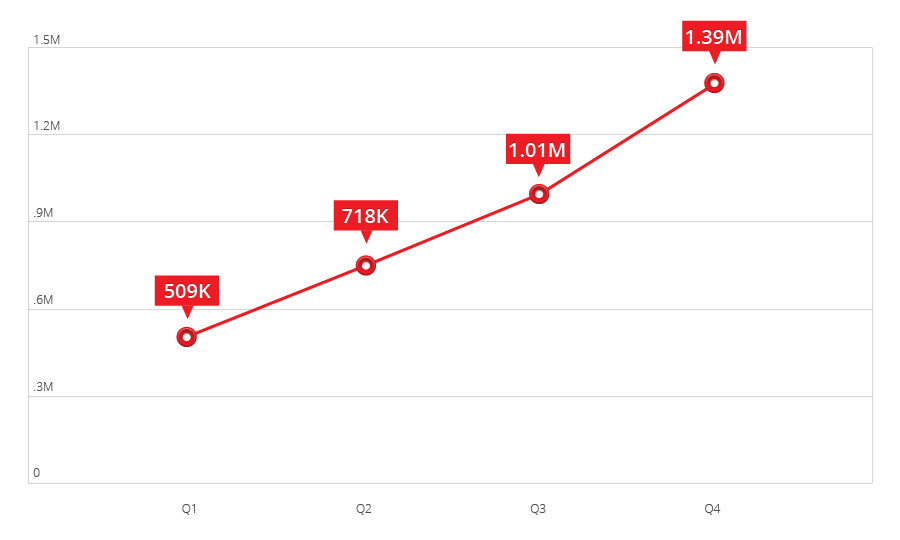

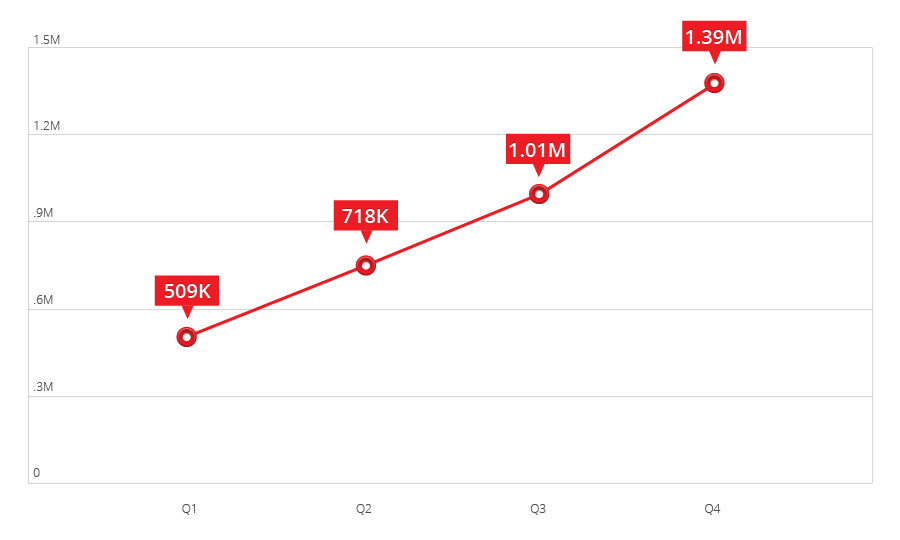

Android Malware Detections

The booming Android market can only be outpaced by the development of Android threats. By the end of 2013, we detected more than 1.3 million malicious and high-risk Android apps, which significantly increased from our 350,000 samples in 2012.

Figure 1: Number of malicious and high-risk app detections in 2013

Around 27% of the detected apps were classified as “high-risk apps”; the remaining 73%) were classified as “malware.”

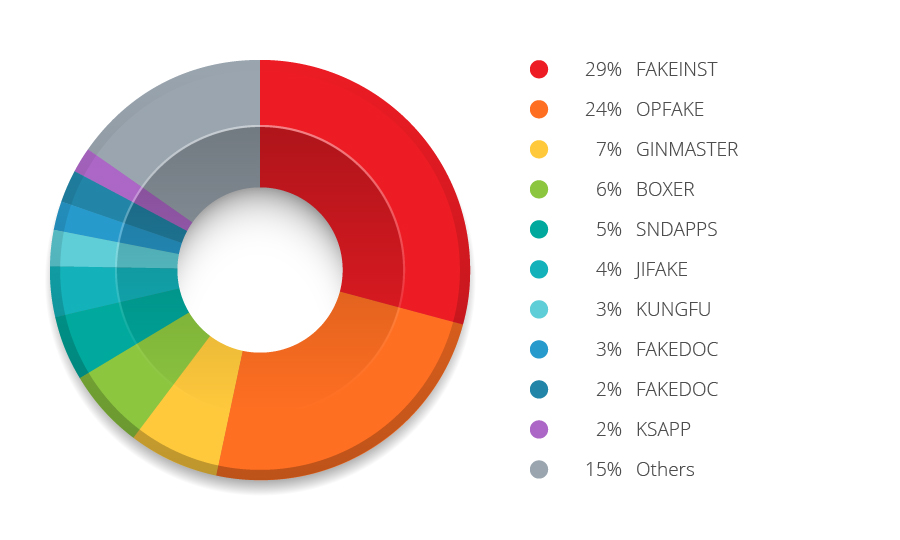

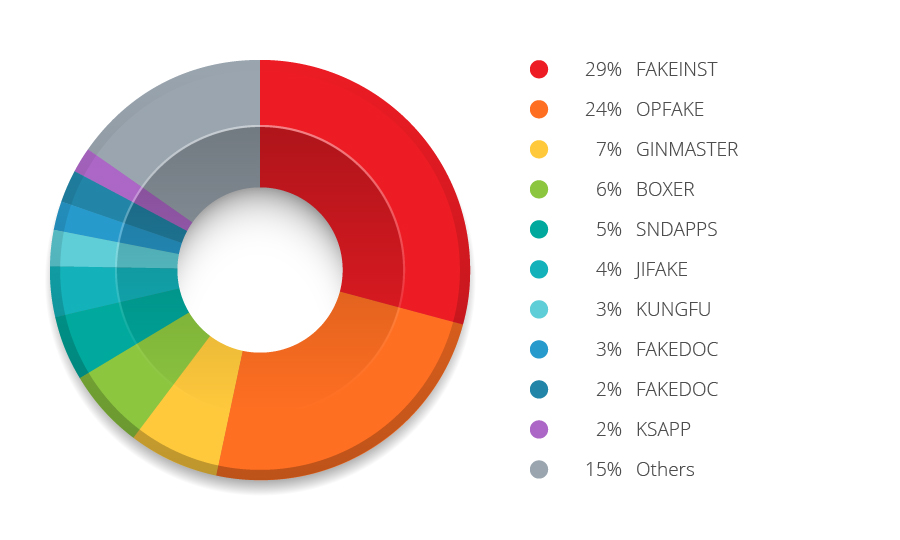

Figure 2: Top malware families as of 2013

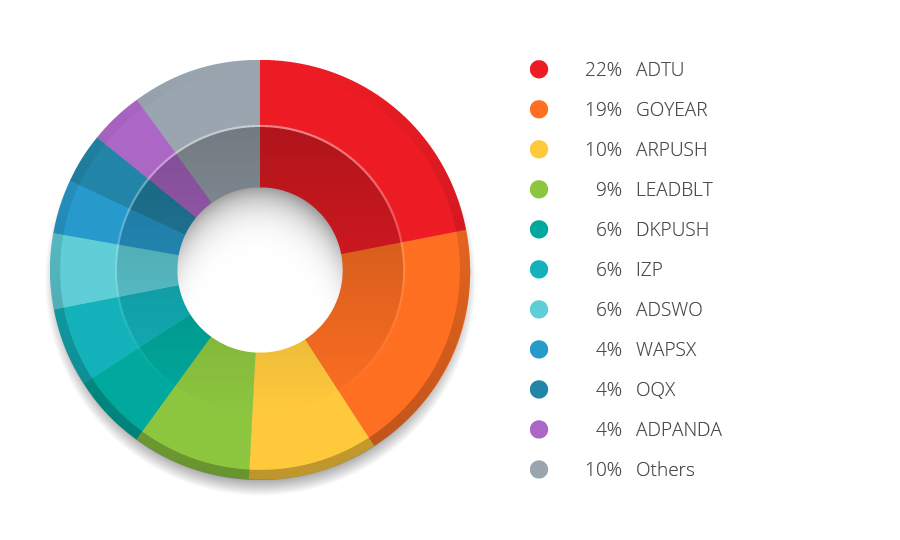

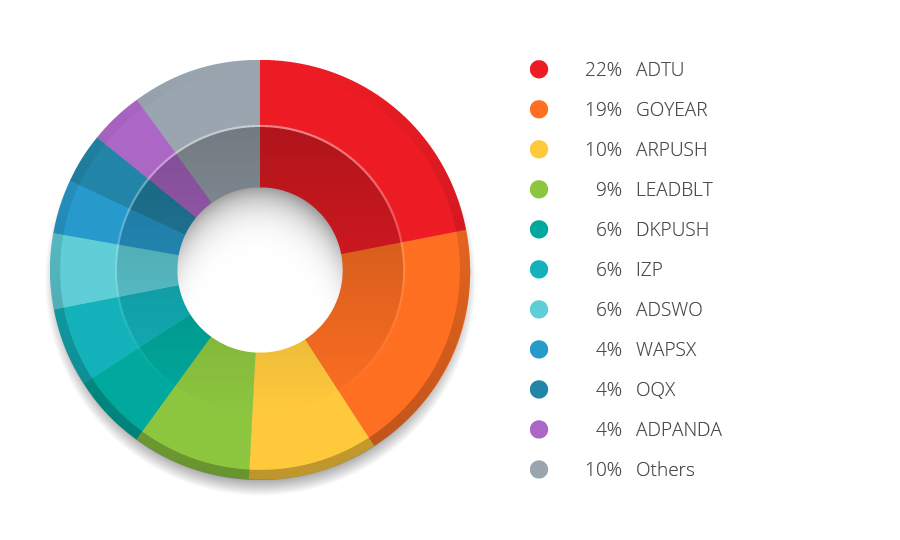

Figure 3: Top high-risk app families as of 2013

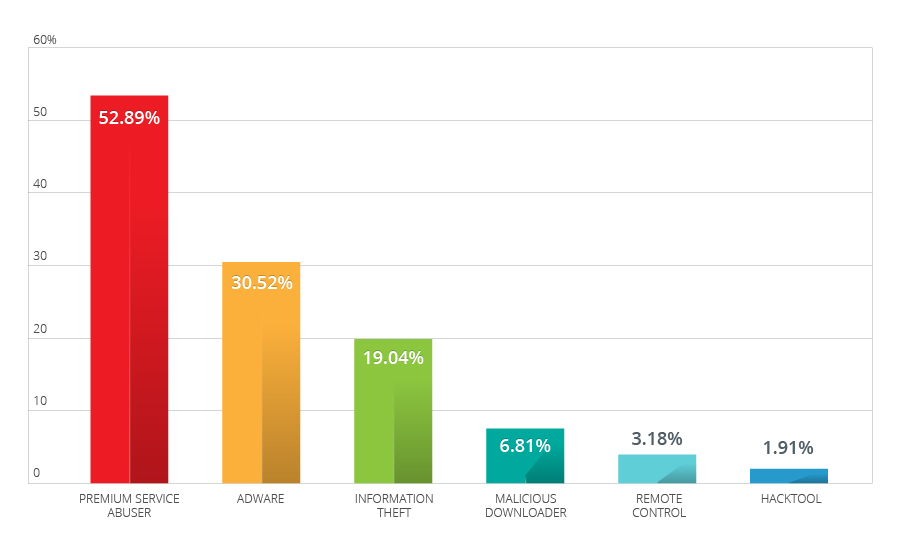

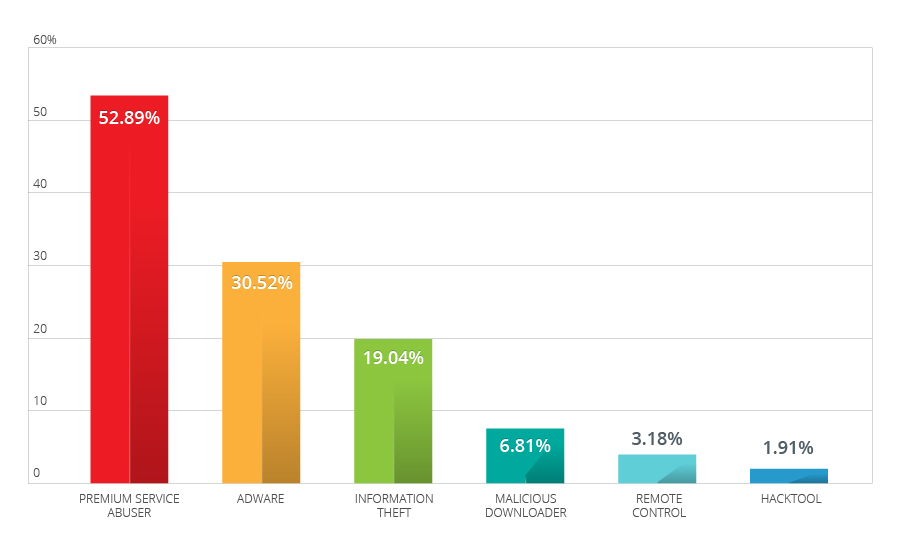

Premium service abusers remained the most common malicious app type, comprising around 53% of all samples. As we said in “Malicious and High-Risk Android Apps Hit 1 Million: Where Do We Go from Here?,” premium service abusers subscribe devices to high-cost services without their users’ consent. Cybercriminals may favor this mobile malware type because they’re easy to create and are less risky to use than others. The other top malware types include data stealers, malicious downloaders, and backdoors.

Figure 4: Top mobile threat type distribution in 2013

Note: The distribution data was based on the top 20 mobile malware and high-risk families that comprise 80% of all the mobile threats detected by the Mobile App Reputation Technology in 2013. A mobile threat family may exhibit the behaviors of more than one threat type.

Notable Developments and Threat Trends

The mobile threat landscape is never stagnant. Throughout 2013, we noticed several developments and trends emerge as cybercriminals continued to tweak and fine-tune their techniques and schemes.

Mobile Attacks Became Highly Specific

Mobile threats don’t typically discriminate when it comes to choosing victims so long as they profit. Now, we see mobile malware target specific victims. ANDROIDOS_SMSSILENCE.VA, for instance, targets South Korean devices by checking for numbers starting with “+82.” Going even further, mobile malware are now used for targeted attacks. ANDROIDOS_CHULI.A, for instance, was used in a spear-phishing attack against Tibetan and Uyghur minorities.

Privacy Loss and Identity Theft Increased

Built-in features and apps have made smartphones a repository of data that range from photos and contact lists to browsing histories and passwords. Unfortunately, cybercriminals can use or sell the data you keep in your smartphone. They can use stored passwords to access your banking accounts or even your basic information to steal your identity.

By the tail end of 2013, almost 24% of the samples we detect have data-stealing routines or capabilities. This number increased from the start of 2013 from only 17%, which shows a growing interest in stealing data off mobile devices. Commonly stolen data include call logs, text messages, browsing histories, phone and network information, contact details, social networking activities, GPS locations, downloads, and app use.

One notable data stealer is ANDROIDOS_KEYLOGGER.A, which repacked a famous typing app, “

SwiftKey,” and used it to collect and upload user information to a remote server.

Scams Became More Rampant

Often enticingly packaged scams made their way to mobile devices in 2013 to lure as many victims as possible. A common vehicle for these were

“one-click billing fraud” apps, which attempted to lure victims interested in adult content and dating services to a site that tricked them into registering for paid services they may not want to.

One-click billing fraud apps don’t normally require permission acceptance; some only ask for Network Communication permission. In this case, asking for user permission was only a ruse to convince victims that the malicious app is legitimate. While these are no longer new, they are becoming more popular among cybercriminals. According to Trend Micro data, the number of one-click billing fraud samples in the second half of 2013 increased more than 10 times compared with that in the first half.

Some apps can also push

scams via ads that often sported attractive titles to encourage clicks. Clicking then either directed victims to malicious Web pages or led to the download of malicious apps. In 2013, we saw fraudulent sites promoted via ads that sold “hot items” like the iPhone® 5 or the Samsung Galaxy Tab™ at extremely low prices but, in reality, directed victims to fraudulent sites. What differed was that these ads were delivered by large, mainstream ad networks that claim to be used by more than 90,000 apps.

Vulnerabilities Became a Hot Target

Much like computer vulnerabilities, mobile device vulnerabilities also became a serious security concern. 2013 started with

Samsung addressing a previously reported

vulnerability in Android devices with Exynos chipsets. This allowed any installed app to access a phone’s entire memory. An attacker can abuse this vulnerability to gain root access to and complete control over the device. Even though this bug has been addressed, the still-fragmented Android update process can still leave some devices vulnerable.

In mid-2013, we saw some customized phone ROMs in third-party stores that can grant root privileges and execute commands. Malicious apps came preinstalled in mobile device ROMs. These can update themselves, recommend other apps to download from stores, be registered as auto-start services, or run commands that require root privileges.

One such malware variant, OBAD, became notorious in the middle of 2013 by exploiting Android vulnerabilities.

OBAD malware ask for root and Device Administrator privileges. Once granted, it runs on stealth mode and can be invisible even in Device Administrator Management view. Even worse, it will be hard to uninstall it because it has Device Administrator privileges. OBAD can also spread via

Bluetooth®, a rehashed technique that suggests that cybercriminals are going beyond app store use to victimize users.

Android vulnerabilities often got the media’s attention in 2013 but none of them got more than the

“master key” vulnerability. This allowed installed apps to be modified without alerting a device’s user, which meant that any installed app can be turned malicious. To make matters worse, almost all Android devices remains vulnerable until now, given that the bug has been there since Android 1.6 (Donut). In 2013, it didn’t take long for bad guys to exploit this vulnerability, as within the same month of its discovery, bad guys abused it to Trojanize a

Korean banking app.

Multiplatform Attacks Increased

Android-PC combination attacks are no longer new though we saw more variations of this attack type in 2013. One of the earliest known such malware is

ZitMo, which we first reported about in 2011. This targeted mobile devices running on BlackBerry® OS, Symbian, and Windows Mobile. With Android’s dominance, it only seems natural that cybercriminals have shifted their platform focus. SpitMo, used in tandem with Windows malware;

SpyEye; and CitMo, used with

Carberp, are Android malware that steal transaction information, particularly mobile transaction authentication numbers (MTANs). MTANs are often used as one-time passwords for financial transactions as part of two-step verification. Stealing MTANs can bring bad guys one step closer to getting into victims’ financial accounts. This type of interception is expected to spill over into 2014, as more mobile malware render

two-step verification lacking against threats.

Though it’s known that PC malware can launch mobile attacks, we’ve also seen Android malware do the opposite. USBATTACK, for instance, downloads Windows malware when an infected USB is connected to a computer. USBCLEAVER, meanwhile, can steal information like passwords and system information if an infected USB is connected to a Windows computer.

The Future of Mobile Threats

We expect cybercriminals to use more obfuscated and native codes.

Bad guys will invest in more advanced encryption and obfuscation tools to protect their malicious apps from detection. This will make it more difficult to detect and analyze malicious apps.

We believe Android malware production will increase and become more industrialized.

We see the Android malware market growing even bigger. OPFAKE/Boxer malware are considered the earliest SMS Trojans and the first to try to targeting multiple countries at the same time. These came from several Russian sites that have been there for years. Data showed that the number of detected OPFAKE/Boxer variants doubled since the start of 2013. The family was also included in the top 10 malware families of 2013.

We expect large-scale buying and selling of mobile botnets in the near future. The common tasks botnets will do include receiving commands from remote servers, mass spamming, launching distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and leaking stolen data. These tasks don’t require much computing power and can be easily achieved on smartphones. The MTK botnet and the OPFAKE family are proof that mobile botnets have become a common means to gain profit.

We will see a new bug that’s as severe as the master key vulnerability.

The existence of the master key vulnerability showed how Android’s app integrity check during installation can be circumvented. This may encourage cybercriminals to look for new bugs like the master key vulnerability.

Note: Trend Micro detects apps that use ad libraries that typically gather information without offering any “opt in/opt out” option for users. While ad companies have since made considerable efforts to improve their data gathering, older versions of their libraries are still used by the apps we detect.

HIDE

Like it? Add this infographic to your site:

1. Click on the box below. 2. Press Ctrl+A to select all. 3. Press Ctrl+C to copy. 4. Paste the code into your page (Ctrl+V).

Image will appear the same size as you see above.

Complexity and Visibility Gaps in Power Automate

Complexity and Visibility Gaps in Power Automate AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization

AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization Ransomware Spotlight: DragonForce

Ransomware Spotlight: DragonForce Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One

Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One