Your Stolen Data for Sale

Although this paper is about stolen data, how it’s being sold on criminal marketplaces, and assessing the risks of users having their data stolen, infostealers are an important piece of the puzzle as the original source of stolen data.

Infostealer malware is a type of malicious software that cybercriminals use to extract sensitive information from a victim’s computer or mobile device. They are specifically designed to steal data, such as credentials, credit card and financial information, and other critical information, that can later be used for other fraudulent activities. This data, which can be stolen from the browser’s saved passwords or from browser cookies, could allow the criminal to bypass multiple factor authentication (MFA), which is very valuable to an attacker. However, this value is time-sensitive; it’s only good based on how long a session remains open with each affected account.

Infostealers continue to be a prominent threat because of the increasing value of stolen data on the black market. Cybercriminals can sell the stolen credentials to impersonate victims, enter their corporate networks using a VPN, commit other kinds of fraud, or sell such credentials to others. Additionally, with information increasingly being stored online, infostealers have become an effective tool for attackers, especially against organizations that store large amounts of sensitive data and lack comprehensive security measures. The growing trend of remote work and cloud storage solutions has also created new opportunities for infostealer attacks.

In addition to understanding what infostealer malware is and why it continues to be so prominent, it is also important to recognize the real-world impact that data theft has on individuals and organizations.

Cybercriminals sell stolen data on the dark web, a hidden part of the internet where illegal activities often take place. On the dark web, data is sold in various forms, including complete databases or individual records, such as social security and credit card numbers. We give an in-depth view of this topic in our report, “Cybercriminal Cloud of Logs: The Emerging Underground Business of Selling Access to Stolen Data.”

The value of individual stolen data varies depending on its type, quality, and availability. For example, credentials for a bank account with a high balance will be much more valuable than those for a social media account. The more data is available about an individual, the more valuable and susceptible to misuse and fraudulent activities it becomes.

It’s essential for individuals and businesses alike to understand the market for stolen data. This will allow them to take the necessary precautions to safeguard themselves against data breaches and to implement strong security measures to protect their sensitive information.

The contenders

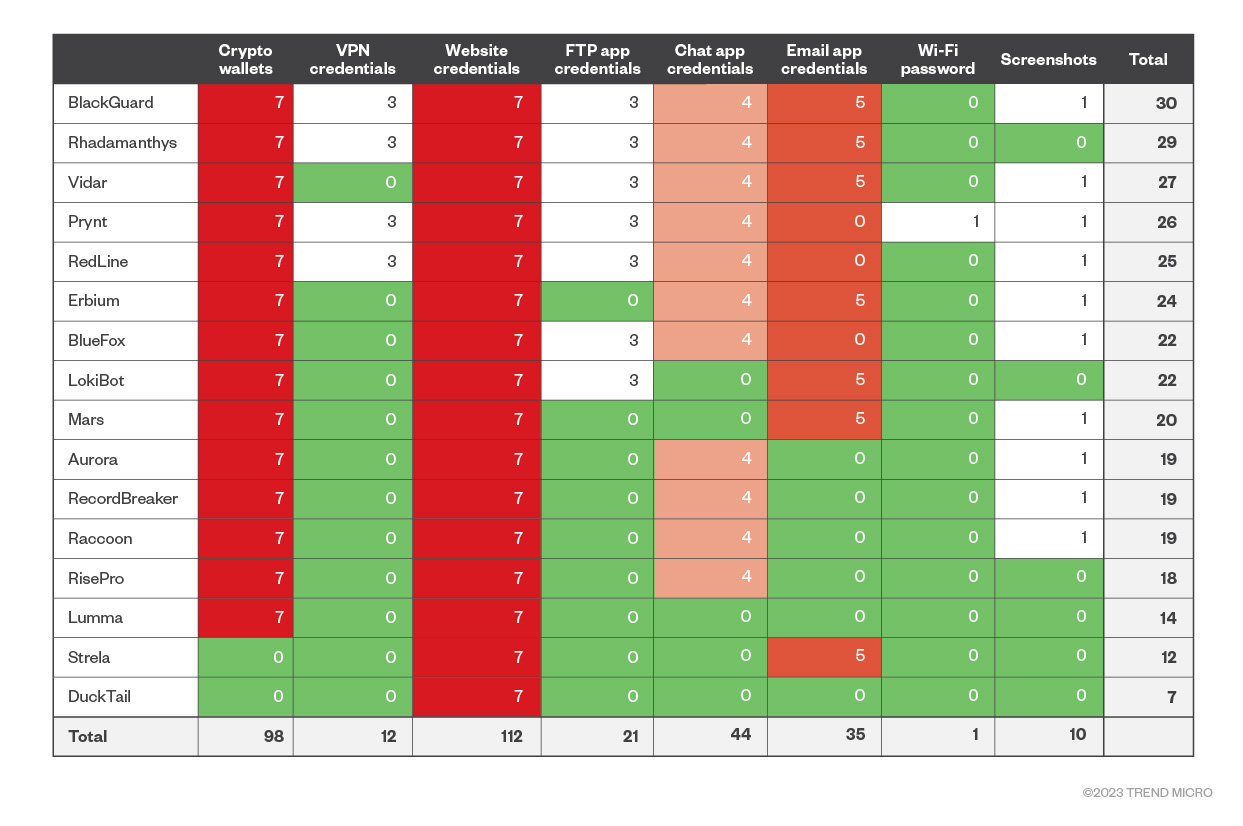

To better understand the risk associated with a possible data theft, we compared the 16 most active infostealers in recent years.

When comparing the stealing capabilities of each infostealer, they appear to be quite consistent in the types of data they target:

- Browser data is by far the preferred target for data stealers. This is not surprising, given that browser data is a treasure trove of sensitive information, including authentication cookies, stored credit cards, credentials, passwords, and navigation history. Many of today’s browsers share the same architecture, either based on Chromium (Google Chrome) or Proton (Firefox), so it is expected that an infostealer targeting one of those will automatically "support" different browsers that use the same architecture. Aside from Chromium- and Proton-powered browsers, such as Google Chrome, Firefox, Edge, and Opera, we were surprised to find the number of obscure or legacy browsers that are also being specifically targeted.

- Another sought-after target is any crypto asset contained in crypto wallets, such as NFTs and coins, either by directly looking for the wallet file or via browser extensions (which can be found by looking for the crypto exchange site credentials). This also makes sense considering how actionable the data stolen is. We will provide more details on this in the succeeding section.

- There's a vast selection of other software being targeted to steal users’ credentials, such as mail or FTP clients, chat and gaming platforms, and VPN profiles. Each individual stealer supports some, all, or none of those.

- A notable mention should go to the DuckTail stealer, which ignores most of the above and focuses its efforts solely on getting Facebook profile data.

Data actionability

The first metric we can use when comparing different infostealers comes from what we call “data actionability.” Data actionability measures how easily a piece of stolen data can lead to an economic gain for a criminal and, subsequently, an economic loss for the victim.

If we think of one’s data as a physical wallet, in the unfortunate case that the wallet gets stolen, we can assume the following:

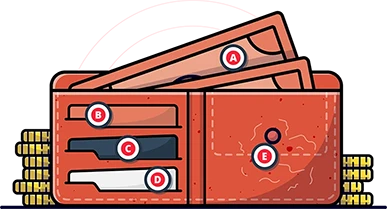

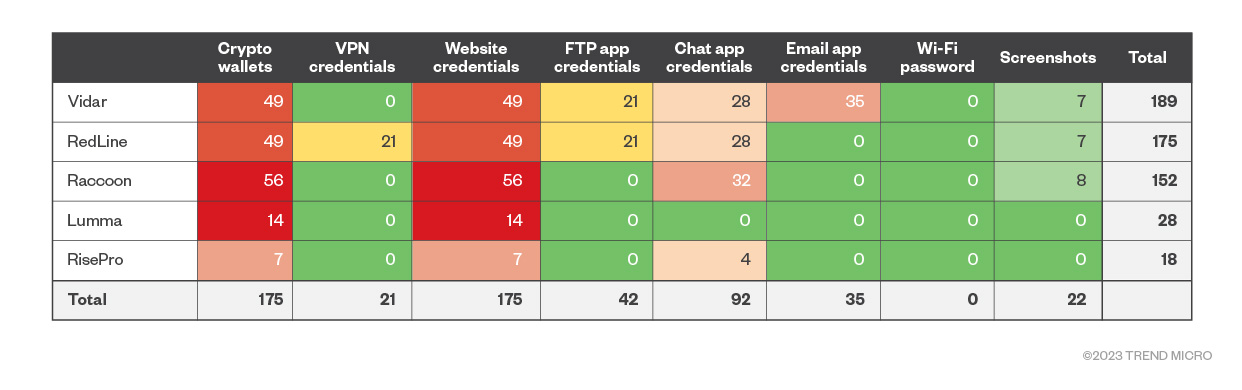

We’ve then assessed the data actionability scores of the top 16 infostealers to better understand how each one works and how it would negatively impact their victims. The data types featured in Figure 1, such as crypto wallets and VPN credentials, are the data types that these featured malware families typically exfiltrate from victims. The total for each malware family shows just how actionable the data they steal is.

Figure 1. Infostealers (and their main capabilities) vs. data actionability (on a scale of 1-5, with 5 being the most actionable)

Figure 1 shows how the different infostealers fare in terms of actionability of the stolen data, putting BlackGuard, Rhadamanthys, and Vidar on top of the list. Unsupported data types by specific infostealers get a score of zero. For example, Raccoon doesn’t support the stealing of VPN app credentials. The risk matrix of Figure 1 essentially represents how likely a user is to face a direct economic loss if they get hit by a specific infostealer.

In-the-wild popularity

While the data actionability table in Figure 1 becomes interpretable post-infection — it assesses how at risk the data is once it has already been stolen and the infostealer is known — how would we know how at risk the data is before it gets stolen?

To estimate that, we need to attach a likelihood to each infostealer, based on a measurement of each infostealer's popularity in the wild, which enables independent interpretation.

To achieve that, we used data from VirusTotal to gather a measure of each infostealer’s popularity level in terms of mentions based on rules and detections, among other factors. We have counted each family’s mentions and used them to place each infostealer into six buckets of uniform density:

- RedLine, with more than 2 million mentions in VirusTotal, gets the top bucket, with a score of 6.

- LokiBot (245,000 mentions), Mars (223,000 mentions) and Aurora (185,000 mentions), were assigned a score of 5.

- Vidar (47,000 mentions) was assigned a score of 4.

- Racoon (11,800 mentions) and Rhadamanthys (11,100 mentions) were assigned a score of 3.

- Erbium (3,300 mentions), RecordBreaker (2,800 mentions), BlueFox (2,000 mentions), DuckTail (1,700 mentions) got a score of 2.

- Finally, Lumma, (1,000), Prynt (800), Strela (700), BlackGuard (400) and RisePro (300) received a score of 1.

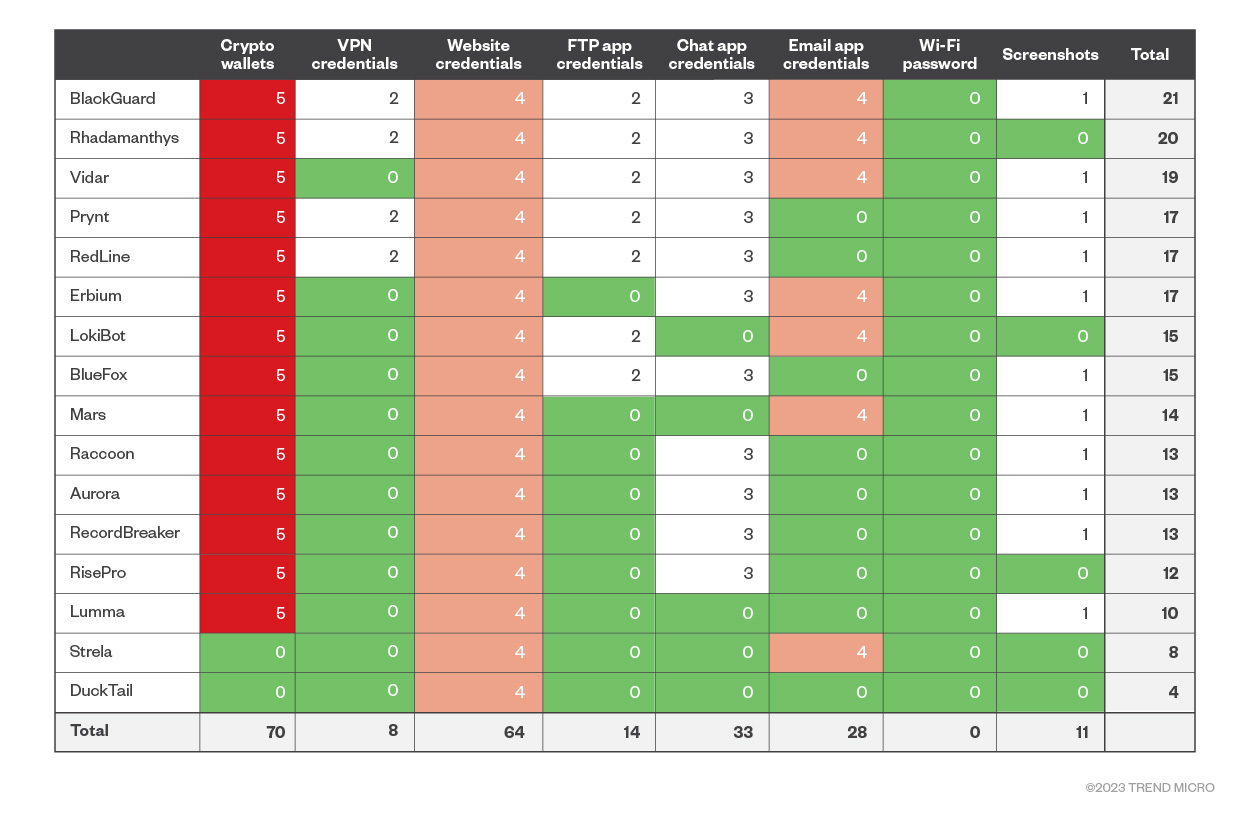

Figure 2. Infostealers vs. in-the-wild popularity levels

Figure 2 combines the actionability metric of Figure 1 with the bucket value we just computed. As a risk matrix, it shifts the risk analysis from a post-infection risk of Figure 1, where the risk data depends on the infostealer that targeted a user, to a pre-infection risk that uses the in-the-wild popularity of each infostealer to estimate how likely it is to hit a user.

When read by column, it ranks infostealers by their general danger level based not only on the data that they steal, but also on their popularity. Based on these factors, RedLine has risen to the top of the ranking due to its popularity, followed by Vidar, LokiBot, and Mars infostealers. We can also read it by row and obtain an estimate of how at risk each data type is based on how many infostealers target it and how popular each of them is. In Figure 2, we can see how crypto wallets remain the most at-risk data due to their high actionability (when a user loses the wallet, the money is also lost), followed by website credentials and chat credentials.

We thought that it would be interesting to see how the information gathered by infostealers is put up for sale on the underground market. To paraphrase George Orwell, "All stolen data is sold, but some stolen data is more sold than others."

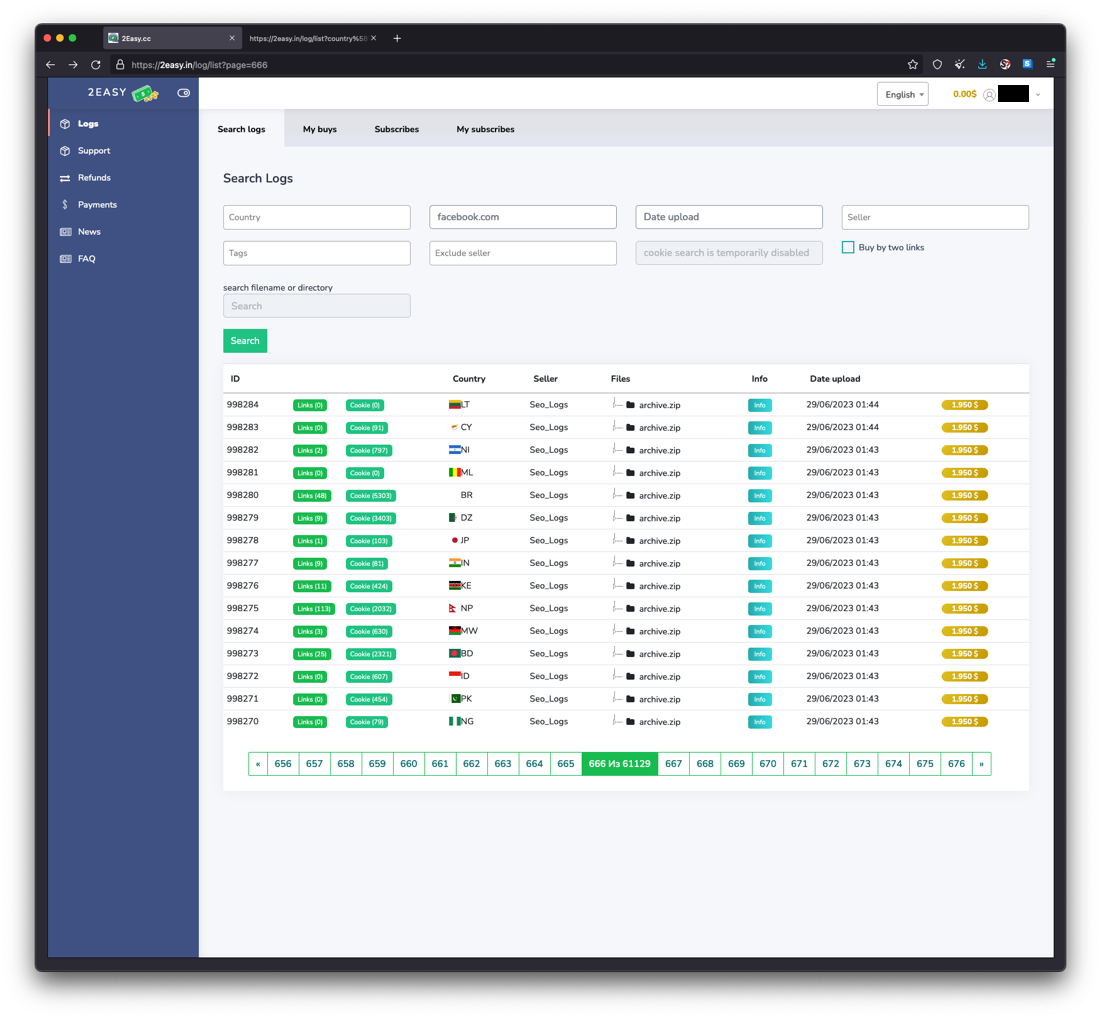

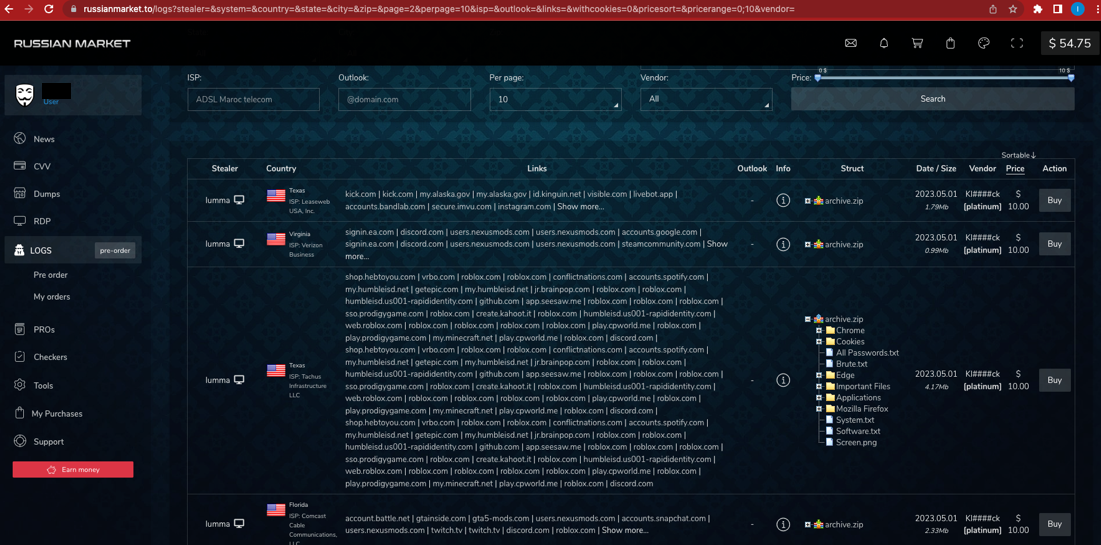

To do this, we accessed two individual marketplaces that are known to sell data dumps from infostealers to see what the search options were on each one. We chose “Russian Market” and “2easy.shop” because of their popularity among criminals and the vast amount of stolen data they have for sale. Both marketplaces present a similar set of functionalities: Users can browse, search, and buy stolen data dumps such as the following:

- Web credentials. The most organized data set indexed by both sites. A potential buyer can search for dumps containing credentials for a specific website in a specific country. This contrasts with, for example, mail credentials that are only searchable on Russian Market, but not on 2easy.shop.

- Crypto wallets. These can be searched via Russian Market's search bar, using a simple keyword search. However, the data needs to be further inspected.

- Microsoft Outlook domain credentials. Russian Market also features a specific search box for Outlook domain credentials, making mail credentials somewhat easier to find and buy.

- Other data. These cannot be specifically searched or filtered but can be inspected in a specific dump by opening the archive.zip file available on each log for sale. This can be done in both marketplaces.

Figure 3. 2easy.shop marketplace

Figure 4. Russian Market marketplace

Based on these observations, we created a new metric called “market availability,” which we defined as follows:

- We assigned a score of 3 to data that we deemed very easy to find in marketplaces, such as web credentials. These are not only easily searchable but can be searched individually by domain, country, and internet service provider (ISP).

- We then assigned a score of 2 to data that is still searchable, albeit with fewer search options. These would be crypto wallets, which are still searchable on Russian Market via a keyword search and can be filtered by country of origin.

- A score of 1 was assigned to any other piece of data that is part of the sale package, is visible on the website, but is not searchable. For example, a user can check if a package for sale contains VPN credentials by inspecting the archive.zip file. However, a user cannot search for packages containing specific VPN credentials.

- Finally, we assigned a score of 0 to items that cannot be searched at all. The data could be in the logs but can only be seen once the log is purchased. These are FTP/Mail/VPN app credentials, Wi-Fi passwords and screenshots.

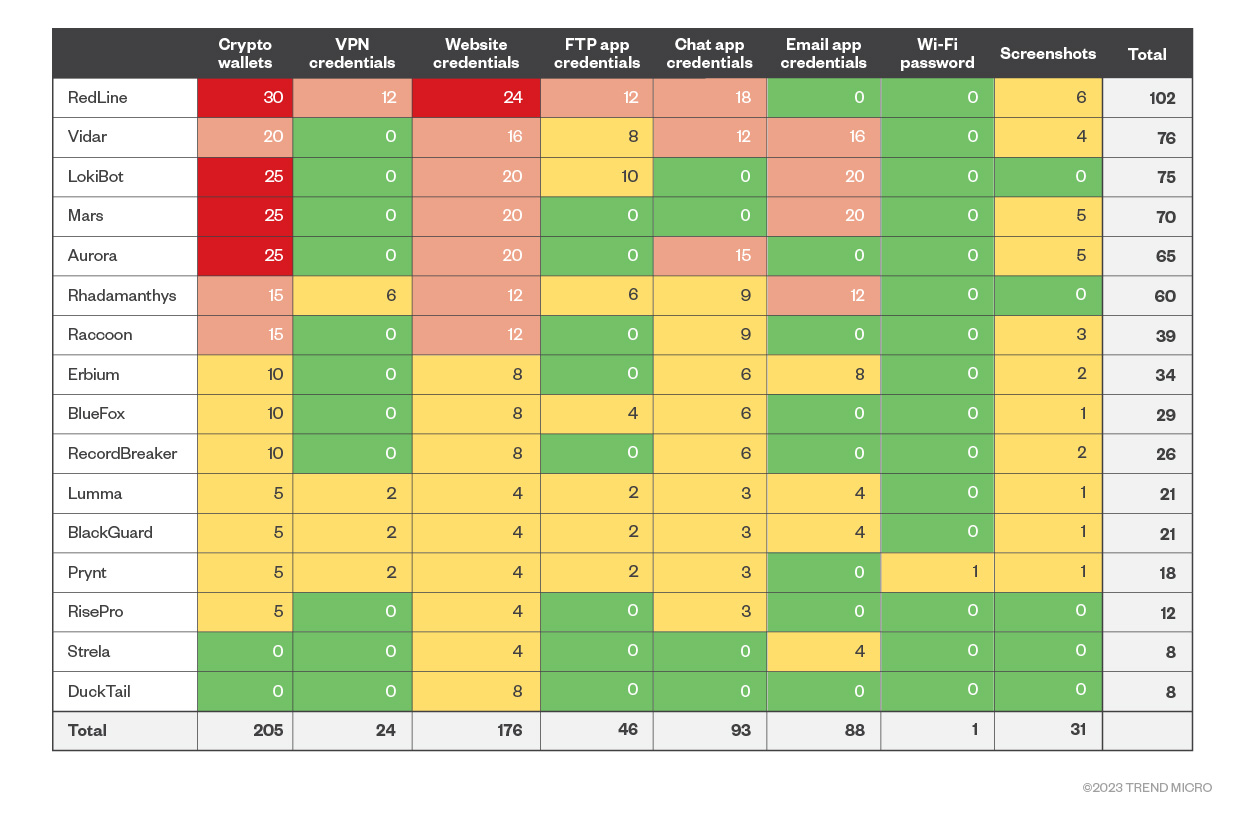

Figure 5. Infostealer vs. data actionability and market availability

Figure 5 compares each infostealer and each data type using a combination of data actionability (Figure 1) with market availability scores. As a risk matrix, it measures how at risk a piece of stolen data is when it ends up in a criminal's hands. This further confirms that crypto wallets and web credentials are not only the most actionable pieces of data but are also the easiest to find and the most indexed in underground marketplaces. Mail credentials, for example, are as actionable as web credentials, but according to our metric, they are harder to find on underground marketplaces. These shops lack proper data indexing for them, except for a specific feature in Russian Market dedicated to Outlook domains.

Just like Figure 1, the risk estimations in Figure 5 provide a sort of post-infection estimate; the estimations make more sense if the name of the infostealer that stole the information is known.

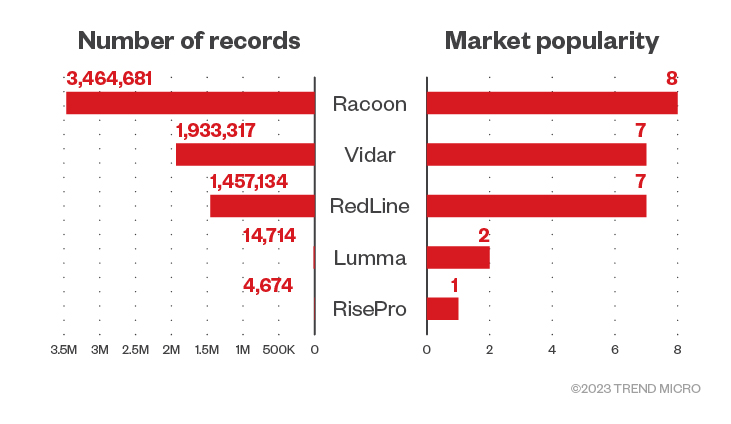

We want to provide a pre-infection risk estimate, or an estimation of the data at risk before the infection takes place. For that, we added an additional metric from data that we’ve derived from underground marketplaces: the number of records sold for each infostealer.

While 2easy.shop only offers records stolen using the RedLine infostealer, Russian Market presents a wider variety of choices, allowing a potential customer to choose records stolen by Racoon, Vidar, RedLine, Lumma, and RisePro.

By comparing the number of records being sold that have been stolen by each individual stealer in Figure 5, we came up with an additional metric that can be combined with the previous market availability metric. This resulted in a prevalence matrix for each stolen data and each supported infostealer:

Figure 6. Number of records and market popularity per infostealer on Russian Market as of May 2023

Figure 7. Infostealer vs. data actionability and market popularity on Russian Market

By multiplying the market popularity score (for Raccoon, for example, the market popularity score is 8 as seen on Figure 6) with the market availability score (which is 7 for crypto wallets on Raccoon as seen on Figure 5), we were able to see which infostealers are popular in the black market. Figure 7 provides a detailed view of the most popular infostealers in the black market, such as Vidar and RedLine. It illustrates an interesting point: Despite the number of infostealers in the wild, only a select few have a significant presence in these underground data marketplaces.

This scenario is different from what we saw in the in-the-wild popularity section where risk was calculated based on infostealer prevalence in general, without focusing on their presence in the black markets. The market popularity section, however, shows us the reality of the criminal data markets in which only a few infostealers are notably dominant.

In practical terms, this data gives us a crucial piece of the puzzle: To safeguard organizations more effectively against data theft, they should focus on the popular infostealers in these cybercriminal marketplaces.

In addition to the risk matrices we’ve discussed in previous sections, the data we were able to gather from underground data shops includes other interesting tidbits that we will present in this section.

The following analysis looks at Russian Market logs. These logs came from computers infected with infostealers. These marketplaces are like eBay in the sense that log owners put the whole data dump on the market up for sale for a specific price. It’s important to note that the data we present in this report is just a snapshot; If we had performed the same analysis on another week or month, it might have yielded different results.

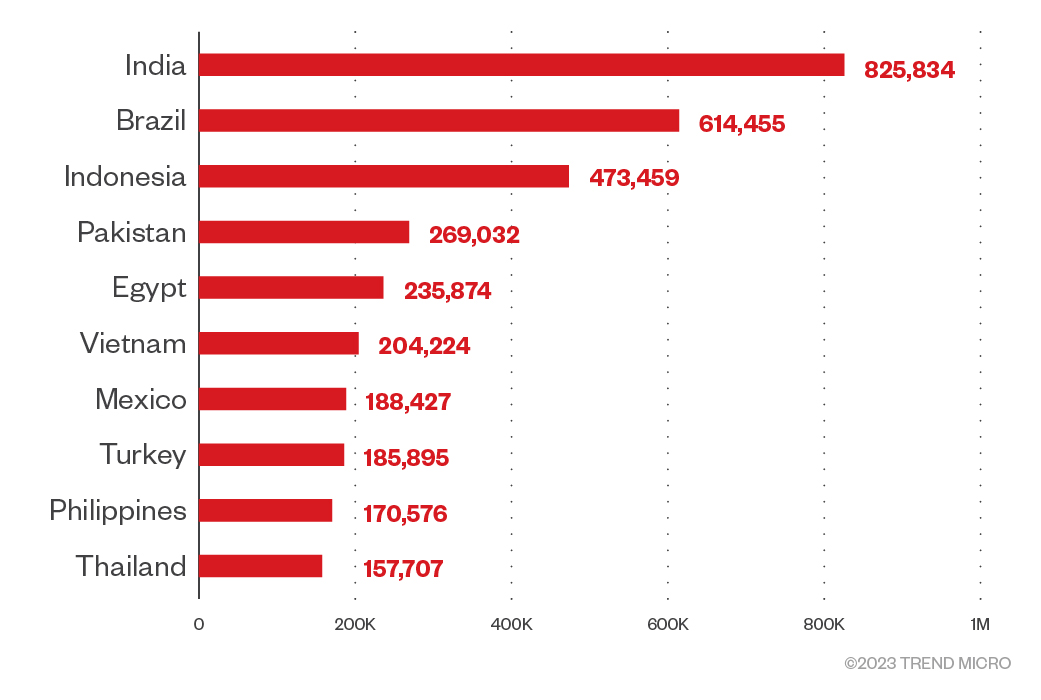

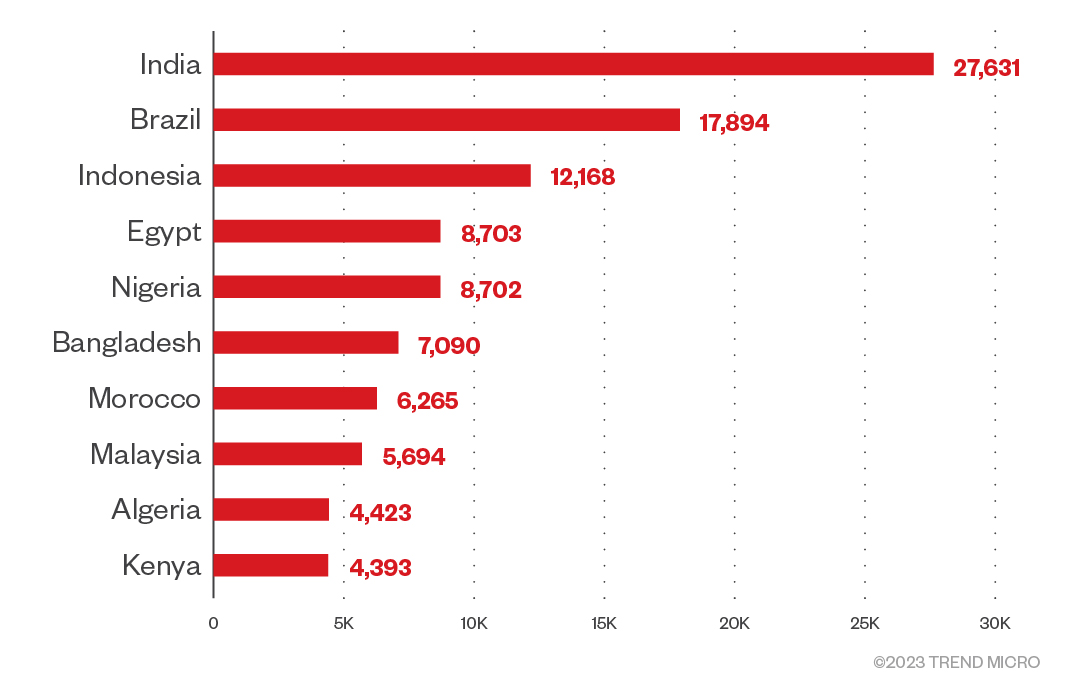

We did not look at personally identifiable information (PII) because that is precisely the type of data criminals pay for. We could only see generic data about the infected computer. As part of that data, we could see the country where the infected computer is located. This allowed us to perform a per country analysis to check which countries are most at risk of being targeted by an infostealer. The data in Figure 8 was collected in May 2023.

Just by looking at the number of logs from each country, we could get a very basic metric of what countries were most at risk. Bear in mind that each log seller could specialize in specific sets of countries. This could skew the analysis, but we have no way to check for that. This is the top 10 list of this very plain metric:

Figure 8. A chart of countries at risk based on the number of logs sold on Russian Market

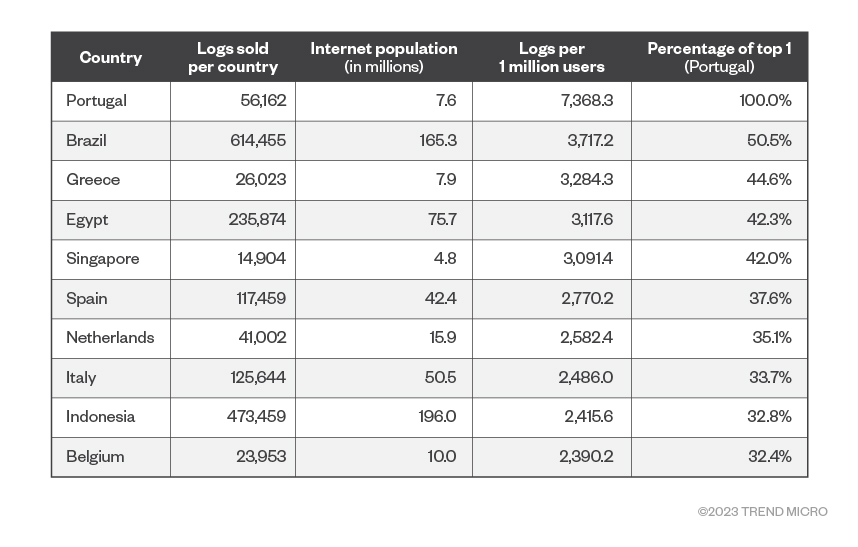

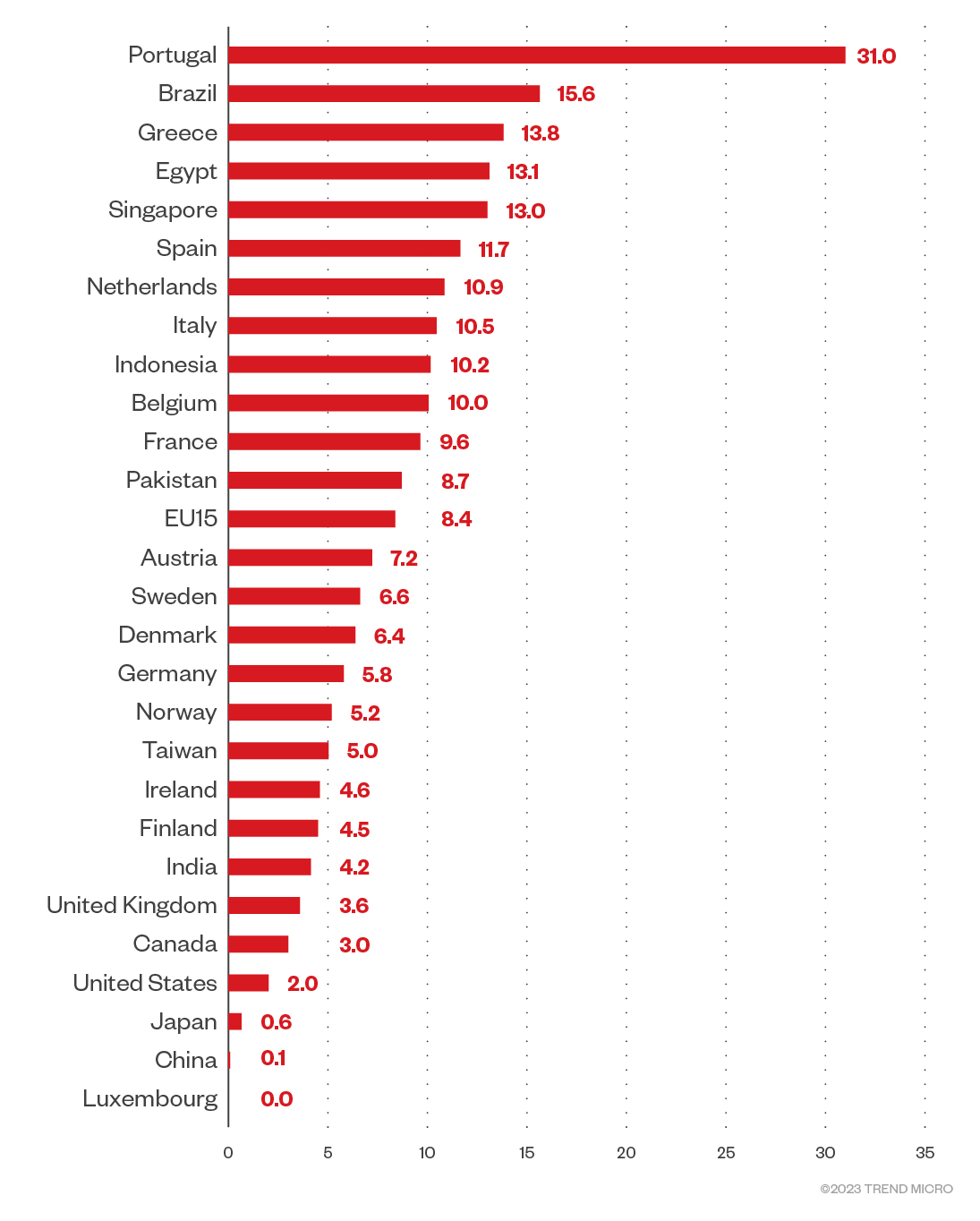

To extract a more accurate infection risk matrix for each country, we weighed each of those infections against the internet user base in each country.1 The top 10 countries we see here are quite different, as the countries with fewer internet users and have many stolen logs will get a higher rank. The key metric here is the number of stolen logs for each million internet users in the country.

Figure 9. Number of logs per country, normalized by each country's internet population

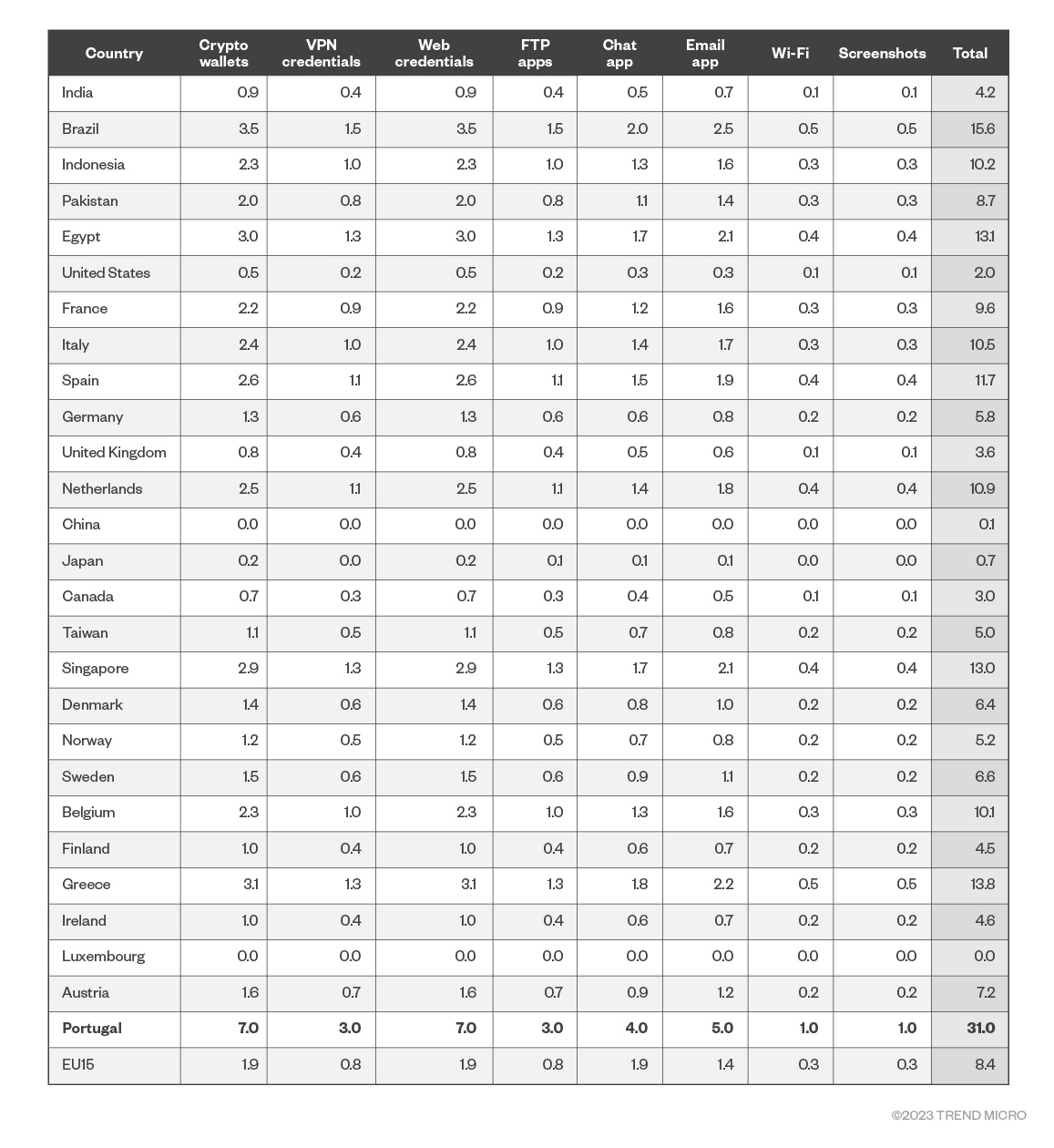

Finally, and to put everything together on this country-based analysis, we want to place a risk rating for each country. We incorporated these findings into the risk matrix in Figure 9. We modified the risk matrix so that we could put a number to the following question: “What is the risk level of each crypto asset (or any of the seven previously described categories) from country X?”

To do this, we reused the risk matrix in Figure 9 that puts risk numbers for each of the assets’ seven categories. In the new “per country risk” table we present in Figure 10, Portugal (the riskiest country) gets 100% of the asset risk (7 for crypto wallets, 7 for web credentials, and so on). The rest of the countries get a percentage of that risk based on their respective “logs per 1 million users” data in comparison to Portugal. For example, the second country, Brazil, had 3,717 logs per 1 million users. That’s 50.45% of Portugal’s 7,368 logs per 1 million users. So, Brazil gets that percentage of the risk per asset, which would equate to 3.53 for crypto wallets and web credentials (the formula for which is 7 multiplied by 50.45%).

1 The main source for internet users per country is Wikipedia. The individual sources for each country are cited at the bottom of the Wikipedia page. Taiwan is not listed on that page, so our source for Taiwan is DataReport. Each figure is dated differently, depending on the source, ranging from 2020 to 2023.

Figure 10. Data risk estimates per country based on logs per 1 million internet population

Note that the right-hand side of the table shows the sum of all the individual risks for each asset per country, which allows us to compare countries’ risk levels. Please also note that Luxembourg did not show up in the logs, it’s just there to reflect that EU15 (The European Union with 15 members) has this country in it. This is the resulting ranked table based on the total risk of all data assets:

Figure 11. The top 20 countries’ total data risk estimates

We performed the country analysis in Figure 11 with data from Russian Market only because 2easy.shop had certain limitations with data downloads that forced us to work with only a subset of the total data. This made it biased and unreliable, so we did not continue with the analysis using 2easy.shop data. For completeness, the top 10 countries on 2easy.shop looked like this:

Figure 12. A chart of countries at risk based on the number of logs sold on 2easy.shop

The similarity between both top 10 tables (from Russian Market and from 2easy.shop) makes us think that perhaps the same data is being sold in both markets. Although this is unethical, it’s a real possibility since criminals are not often bound by ethical constraints. As previously mentioned, these numbers could be biased based on the kind of logs the log owners decide to upload. It could also be a matter of developed countries having a better security posture overall than the countries shown here.

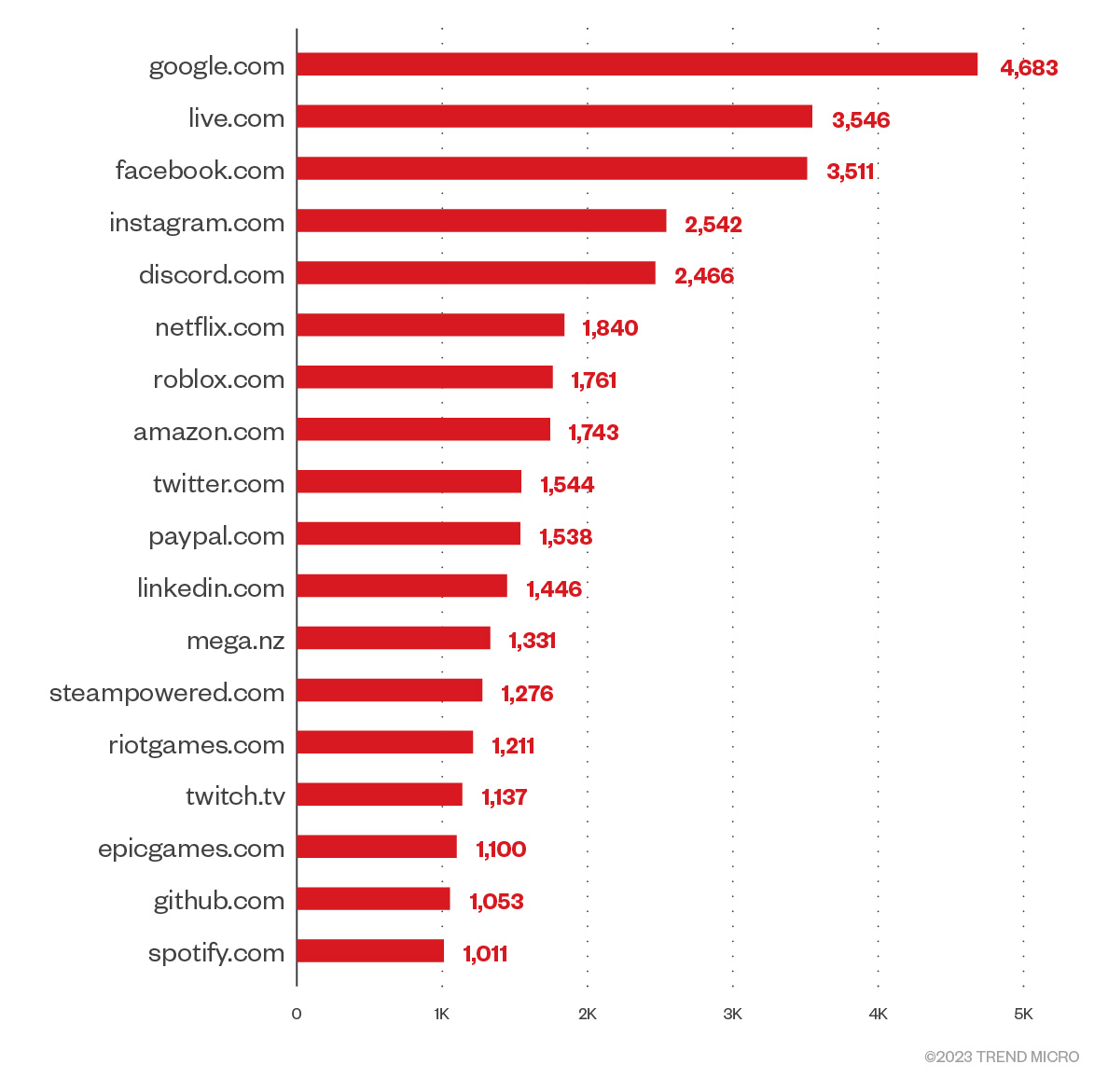

We also looked at which websites’ credentials are the most interesting for criminals to purchase on underground shops. For this, 2easy.shop had better data; We could download a list of all the domains for which they had credentials for sale. This list shows the top domains on 2easy.shop before reaching a very long tail of more obscure domains:

Figure 13. Top domains with credentials on 2easy.shop

Infostealer malware is responsible for most of the stolen data being sold on the criminal underground. Once a victim is infected, their data will be extracted from the machine and put up for sale. Secondhand marketplaces, where all stolen credentials and other personal data end up, have become thriving criminal businesses.

Criminals turn to these shops for quick monetary gain. Malicious actors are always looking for a good ROI: The money they spend on a valid pair of credentials must be less than the money they can get out of them.

The usual ways to monetize stolen user credentials are:

- Draining cryptocurrency wallets

- Exploiting user authentication methods to make transactions on behalf of the user on e-commerce sites and banking sites

- Attacking the victims’ contacts. For example, performing the “stranded traveler” scam that impersonates victims to contact their friends and ask them for money.

- Entering users’ organization through their VPN credentials and performing lateral movement to gain a foothold in the organization.

The previously mentioned list only applies to user credentials. However, infostealers can exfiltrate more than that. The ways to monetize other information are rarer, so, for now, we left that analysis aside.

An analysis of these shops can be very telling of the kind of stolen data offered to enterprising criminals: all these logs came from infostealers. This means that victims’ machines have been infected by malware that is able to steal personal information.

After categorizing this stolen information according to its type, we saw that the most at risk are cryptocurrency wallets and website credentials. Although these infostealers can extract a variety of data, these two categories are the riskiest because they can be very easily monetized. Other categories, like Wi-Fi credentials and desktop screenshots, are not so easy to sell or abuse, and are therefore categorized as less risky. In the middle ground are other credentials that are more specialized, like those for FTP and VPN software.

Based on our observation, these infected computers are located in many developing countries, including India, Indonesia, and Pakistan. However, when we consider each country’s internet population, many other developed countries rise to the top 10 list of targeted countries, such as Portugal, Greece, Singapore, Spain, and the Netherlands.

When we look at the most stolen website credentials, we can see many popular sites, including Google, Live.com, Facebook, and Instagram. Somewhat surprisingly, we can also see other less popular sites that might be more easily monetizable, such as Steam, GitHub, and Spotify.

Personal data is and will continue to be a prime target for criminals because it’s easy to obtain and make money from. Therefore, data shops will remain a staple in criminal communities with its popularity showing no signs of dwindling anytime soon.

Cash

All cash and coins are immediately spendable without traceability.

Data counterpart:

- Crypto wallets

- All crypto-related data

Actionability score

Credit cards

These are items that can lead to an economic loss but can still be averted by contacting the issuing bank to block the cards.

Data counterpart:

- Browser credentials

- Mail credentials

Actionability score

Workplace access badge

There are items that could be harmful in the right context, allowing, for example, a malicious user to perform impersonation or social engineering tactics.

Data counterpart:

- Chat service credentials

- Gaming service credentials

Actionability score

Gym membership card

There are items that are rarely harmful but still contain a user’s personal information. These may be useful when it comes to conducting victim reconnaissance but are hardly usable unless in specific cases.

Data counterpart:

- VPN credentials*

- FTP credentials

*Note: VPN credentials may be very valuable to criminals with the right skills and tools and if the company doesn’t have two-factor authentication (2FA) enabled. This is why we don’t consider them to be immediately actionable, hence their low score.

Actionability score

Lint

These are non-actionable items that are potentially good for the most outlandish deduction by an astute Sherlock Holmes but are mostly useless to anybody else.

Data counterpart:

- Wi-Fi password

- System report

- A screenshot of the victim’s desktop

Actionability score

Like it? Add this infographic to your site:

1. Click on the box below. 2. Press Ctrl+A to select all. 3. Press Ctrl+C to copy. 4. Paste the code into your page (Ctrl+V).

Image will appear the same size as you see above.

Messages récents

- How Unmanaged AI Adoption Puts Your Enterprise at Risk

- Estimating Future Risk Outbreaks at Scale in Real-World Deployments

- The Next Phase of Cybercrime: Agentic AI and the Shift to Autonomous Criminal Operations

- Reimagining Fraud Operations: The Rise of AI-Powered Scam Assembly Lines

- The Devil Reviews Xanthorox: A Criminal-Focused Analysis of the Latest Malicious LLM Offering

Complexity and Visibility Gaps in Power Automate

Complexity and Visibility Gaps in Power Automate AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization

AI Security Starts Here: The Essentials for Every Organization Ransomware Spotlight: DragonForce

Ransomware Spotlight: DragonForce Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One

Stay Ahead of AI Threats: Secure LLM Applications With Trend Vision One