Cyber Threats

The Rise of Collaborative Tactics Among China-aligned Cyber Espionage Campaigns

Trend™ Research examines the complex collaborative relationship between China-aligned APT groups via the new “Premier Pass-as-a-Service” model, exemplified by the recent activities of Earth Estries and Earth Naga.

Key takeaways

- “Premier Pass-as-a-Service” describes the emerging trend of advanced collaboration tactics between multiple China-aligned APT groups, notably Earth Estries and Earth Naga, that are making modern cyberespionage campaigns even more complex.

- The case study discussed in this blog entry shows the model in action between these two groups, with Earth Estries acting as an access broker to Earth Naga for continued exploitation. By sharing access, Earth Estries and Earth Naga further complicate detection and attribution efforts.

- Earth Estries and Earth Naga have persistently targeted critical sectors, especially government agencies and telecommunications providers, with operations spanning multiple regions. Earth Estries and Earth Naga's coordinated cyberespionage campaigns have recently focused on retail and government-related organizations in APAC.

- Trend™ Research has introduced a new four-tier framework that categorizes these different kinds of collaborative attacks and helps security practitioners better understand such collaborations.

With contributions from Joseph C Chen, Vickie Su and Lenart Bermejo

In the domain of cyberespionage, Trend™ Research has observed an emerging development in recent years: close collaboration between different advanced persistent threat (APT) groups of what looks like a single cyber campaign at first sight. This report highlights instances of such cooperation, where the APT group Earth Estries handed over a compromised asset to Earth Naga, another APT group also known as Flax Typhoon, RedJuliett, or Ethereal Panda. This phenomenon, which we have termed "Premier Pass," represents a new level of coordination in cyber campaigns, particularly among China-aligned APT actors.

Attributing cyberattacks to specific threat actors is inherently complex, often relying on a blend of techniques such as malware analysis, network traffic analysis, examination of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and victimology. However, the rise of collaborative operations, such as those exemplified by Earth Estries and Earth Naga, introduces additional layers of difficulty in attribution. These operations challenge traditional methods by involving multiple intrusion sets, complicating the identification of responsible parties.

This report will delve into the intricacies of this emerging trend, focusing on:

- A comprehensive analysis of the Premier Pass case, where Earth Estries facilitated access for Earth Naga, showcasing a sophisticated level of inter-group cooperation.

- The introduction of a four-tier framework to define and categorize modern collaborative attacks among China-aligned APT groups.

- Insights into the attribution challenges posed by these collaborative operations, emphasizing the need for cyber threat intelligence (CTI) researchers to look beyond mere process chain overlaps.

The collaboration discussed in this case study between Earth Estries and Earth Naga marks a pivotal shift in the landscape of cyberespionage, demanding a re-evaluation of attribution strategies and highlighting the intricate web of alliances within the cyber threat landscape.

Earth Estries and Earth Naga victimology

Earth Estries has primarily targeted critical sectors like telecommunications and government entities across the US, Asia-Pacific region, and the Middle East. In the past two years, we have also observed the group expanding its targeting to regions such as South America and South Africa.

Earth Naga has been actively targeting high-value organizations across strategic sectors since at least 2021. Primary targets include government agencies, telecommunications, military-related manufacturers, technology companies, media outlets and academic institutions, with a concentrated focus on entities based in Taiwan (Table 1).

In addition to its operations in Taiwan, Earth Naga has extended its reach to selected organizations in the broader APAC region, as well as in NATO member countries and Latin America, indicating a growing interest in global intelligence collection.

| Intrusion set | Targeted industry | Targeted region | Date |

| Earth Estries / Earth Naga (Premier Pass) | Retail company | APAC | November 2024 |

| Earth Estries / Earth Naga (Premier pass) | Government agency | Southeast Asia | March 2025 |

| Earth Estries and Earth Naga (separate compromises) | Telecommunications provider | APAC | April 2025 |

| Earth Naga | Information service provider | Taiwan | April 2025 |

| Earth Estries and Earth Naga (separate compromises) | Telecommunications provider | NATO country | July 2025 |

Evidence of access broker activities by Earth Estries

Our investigation indicates that Earth Estries operated as an access broker in some campaigns. Specifically, evidence of shared access behavior was identified in the TrillClient attack chains attributed to Earth Estries.

Collaboration between multiple intrusion sets is not unheard of, but we believe there are multiple categories that can be used to describe these types of incidents. Therefore, we will introduce multiple types we know about later in this report.

In two distinct organizational environments that have been persistently targeted by Earth Estries, we identified evidence suggesting that Earth Estries shared access to Earth Naga. This activity indicates a possible operational linkage or access-sharing arrangement between the two threat groups, which may reflect strategic collaboration within a broader threat ecosystem.

The first instance was identified in November 2024, involving a major mobile retail company in the APAC region, where Earth Estries appeared to have provided access to Earth Naga. In addition, our telemetry data reveals that Earth Estries attempted to share access with Earth Naga as early as late 2023. However, Earth Naga’s toolset was detected and blocked by our product during deployment. Therefore, we didn’t observe any network traffic with known Earth Naga command-and-control (C&C) infrastructure at that time.

Subsequently, we identified a second instance of shared access in March 2025, this time involving a government agency in Southeast Asia. Further analysis and indicators related to this case are included in following section.

Earth Estries and Earth Naga’s joint operation

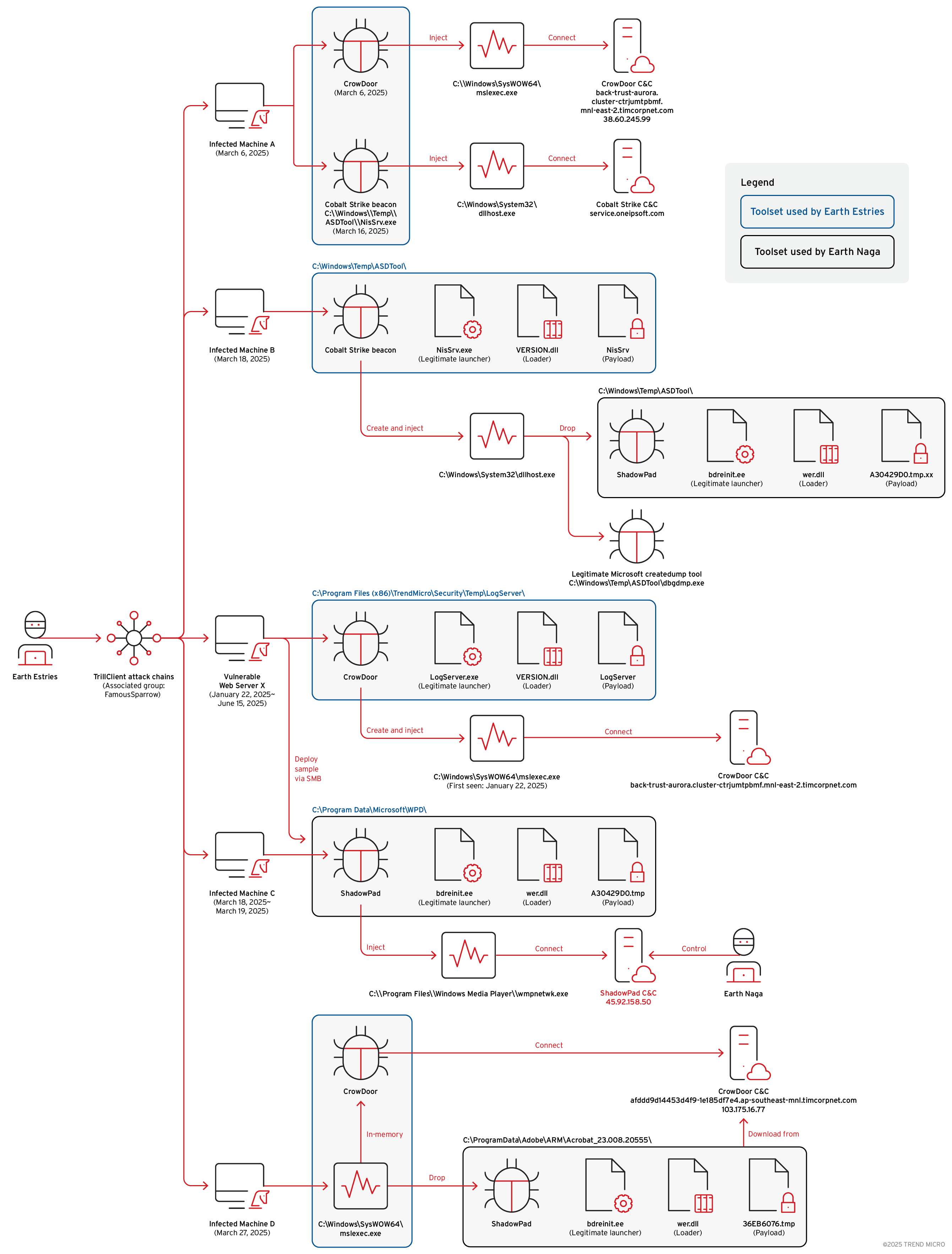

Figure 1 illustrates the attack infection chain we have constructed based on incidents observed within a Southeast Asian government entity earlier this year. These events, which bear strong ties to the activities of Earth Estries and Earth Naga, offer insights into the TTPs employed by these intrusion sets in recent campaigns.

Based on the timeline of observed events, the following key findings were derived from our in-depth analysis of activities linked to Earth Estries and Earth Naga:

1. Initial compromise via vulnerable internal web server (January 2025)

On January 22, 2025, Earth Estries likely leveraged an unmanaged host to compromise a vulnerable internal web server (Vulnerable Web Server X). The attacker deployed the CrowDoor backdoor on the server, which subsequently established communication with CrowDoor C&C infrastructure:

back-trust-aurora[.]cluster-ctrjumtpbmf[.]mnl-east-2.timcorpnet[.]com

2. Lateral movement and deployment of toolsets (March 2025)

In March 2025, multiple Earth Estries-related toolsets were discovered on several internal machines. Due to space limitations, we highlight the four most significant infected hosts: In Figuer 1, these are labelled as Infected Machine A, B, C, and D.

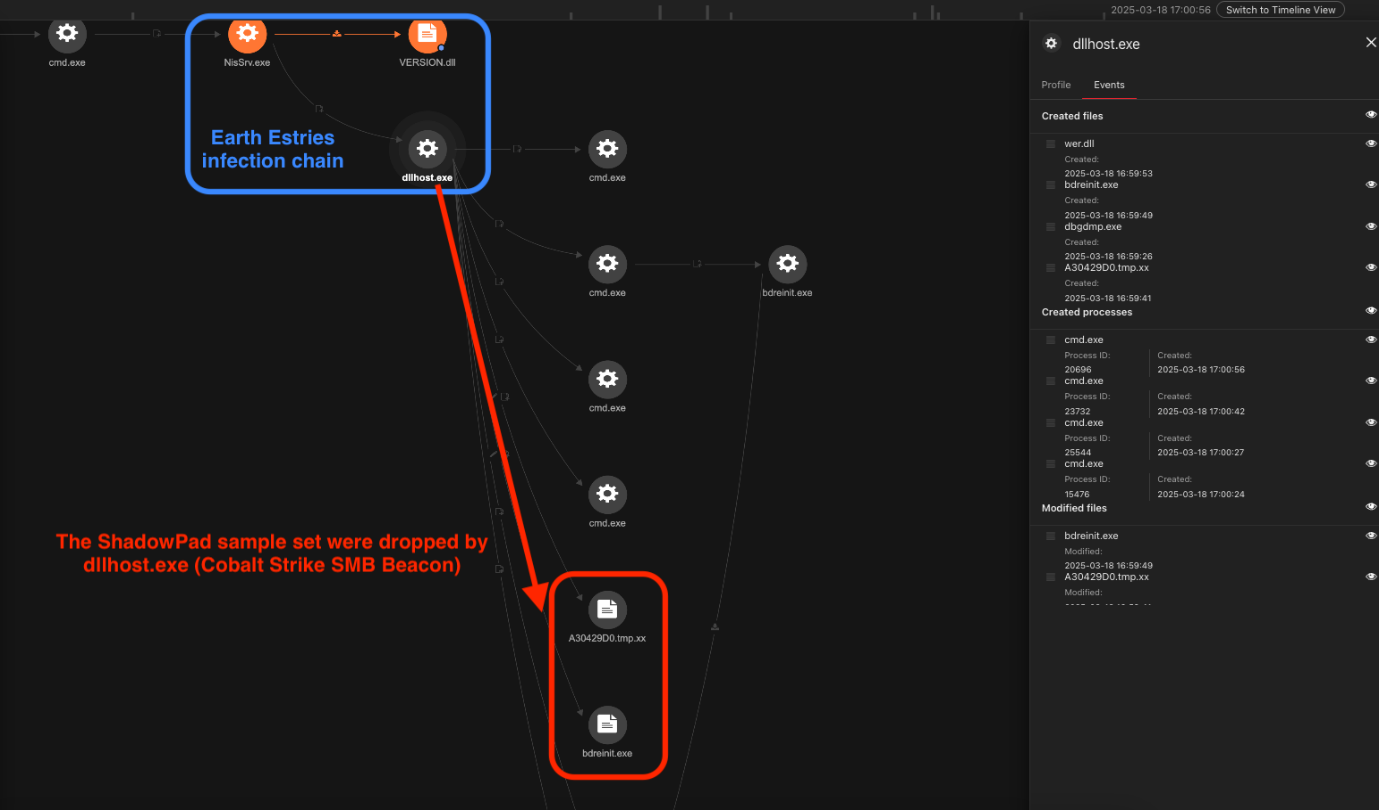

3. Deployment of ShadowPad via Multiple Vectors (March 2025)

Since March 18, 2025, we have identified that Earth Estries has been deploying the ShadowPad backdoor through multiple vectors within the compromised environment. We believe the threat actor tried all these approaches in an attempt to evade detection:

- Deploy malware via Cobalt Strike SMB beacon (Figure 2)

- Deploy malware using compromised user credentials to transfer files via SMB

- Deploy malware via CrowDoor (new variant of SparrowDoor)

On March 27, 2025, we identified the deployment of a ShadowPad malware sample originating from a CrowDoor network session. The session, observed on Infected Machine D, was associated with the following CrowDoor C&C infrastructure:

- C&C domain: afddd9d14453d4f9-1e185df7e4[.]ap-southeast-mnl[.]timcorpnet[.]com

- Resolved C&C IP address: 103[.]175[.]16[.]77

This activity suggests a possible linkage or operational overlap between CrowDoor and ShadowPad toolsets, potentially indicating shared infrastructure or a coordinated campaign.

4. Attribution of ShadowPad to Earth Naga

The ShadowPad C&C server 45[.]92[.]158[.]50 is linked to known Earth Naga C&C infrastructure. This marks the second observed instance of Earth Estries deploying a known Earth Naga backdoor within a victim’s internal network.

Malware toolkit

The following malware families were involved in this incident:

- Draculoader - a generic shellcode loader. We observed the final decrypted payload could be CrowDoor, HEMIGATE and CobaltStrike beacon

- Cobalt Strike - an offensive framework used by all kinds of threat actors

- CrowDoor - a malware family used by Earth Estries

- ShadowPad - a malware family used by multiple advanced China-aligned threat actors

The CrowDoor infection flow is as follows:

LogServer.exe -> VERSION.dll -> LogServer (payload)

- LogServer.exe - Legitimate Microsoft launcher vulnerable to DLL side-loading

- VERSION.dll - DRACULOADER loader. The payload filename is the same with the host process filename minus the file extension

- LogServer - This is an encrypted shellcode payload form of a backdoor known as CrowDoor

- C&C server: back-trust-aurora[.]cluster-ctrjumtpbmf[.]mnl-east-2.timcorpnet[.]com

The ShadowPad infection flow is as follows:

bdreinit.exe -> wer.dll(loader) -> 36EB6076.tmp/A30429D0.tmp (payload)

The ShadowPad samples were of the same variant that we described recently, however with different DLL filenames being side-loaded:

- Bdreinit.exe - Legitimate executable signed by BitDefender vulnerable to DLL side-loading

- wer.dll - Malicious DLL loading the encrypted ShadowPad payload

- 36EB6076.tmp or A30429D0.tmp - Encrypted ShadowPad payload, encrypted to the Windows registry and removed after the first launch of the malware

Post-exploitation tools

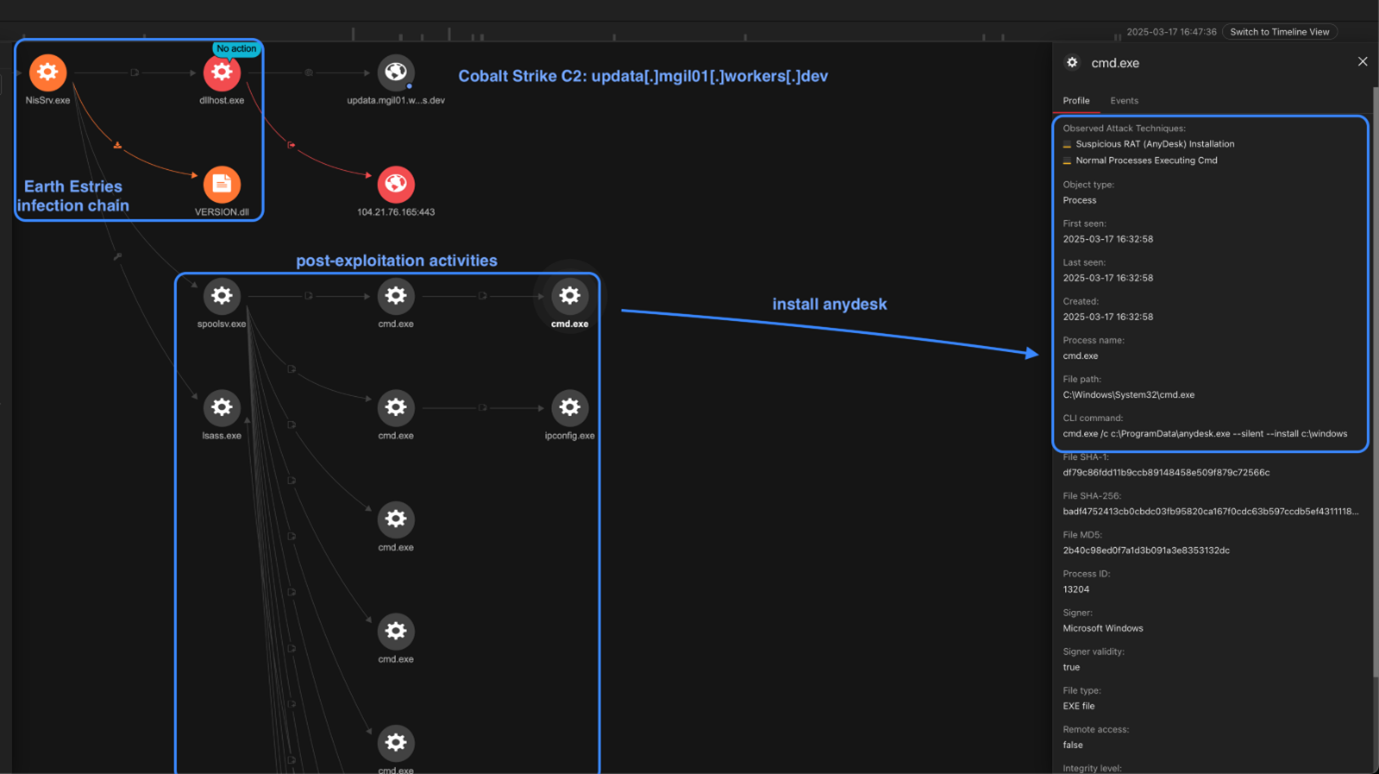

We observed Earth Estries using the following post-exploitation tools (Figure 3):

- AnyDesk

- A VMProtected version of EarthWorm, a SOCK5 network tunnel

- Blindsight, a publicly available tool to dump LSASS memory with evasion techniques based on transactional NTFS

- A custom tool dumping memory from its loading process, probably used as security support provider (SSP) to dump LSASS memory, detected as HackTool.Win64.MINIDUMP.ZALL

Recent activities targeting a major telecommunication provider

Between late April and late July of this year, we detected attempts by Earth Estries and Earth Naga to gain access to at least two top telecommunications providers located in the APAC region and NATO member countries.

Both Earth Estries and Earth Naga have demonstrated distinct, long-term targeting of specific organizations. In April, we observed that Earth Naga gained access to the checkpoint mail server of a leading information service provider in Taiwan. They connected to their C&C server using the wget command. Subsequently, our gateway product detected that the attackers attempted to use the checkpoint mail server to establish SSH connections to other internal network hosts.

Starting in July, we identified Earth Estries exploiting CVE-2025-5777 to attack Citrix devices. In the past, we observed both Earth Estries and Earth Naga targeting edge devices from Ivanti, Cisco, and others.

Modern APT collaborative attack definitions and types

The previous study illustrates the complexity of attribution for modern cases. In this section, we aim to set some definitions of what constitutes a modern APT collaborative attack online, as observed through our analysis.

In the past, we have observed that many intrusion sets leverage multi-stage backdoor mechanisms to ensure persistent access and control. In most cases, when a connection within the process chain is identified, we attribute all stages of the backdoor to a single intrusion set.

However, here we aim to present a scenario in which, when the following three criteria are met, a more plausible explanation is that multiple threat groups may be collaborating. Therefore, the attribution of espionage operations cannot solely rely on process chain analysis. Similar to how “ORB networks” operate as infrastructure providers, it is also plausible that a specialized access broker service exists to facilitate such collaboration.

That said, the presence of different malware sample sets should not be immediately interpreted as evidence of a collaborative relationship, as intrusion sets may deploy backdoors through various independent means without the cooperation or knowledge of the affected parties.

- Rule 1: No traces of compromise of the intrusion set were noticed. For example, no process or network hijacking activity was identified during the operation.

- Rule 2: The malware is deployed in the same process or network session.

- Rule 3: The next stage malware or C&C infrastructure cannot be attributed to the same threat group.

Next, we present a categorization of collaborative attack types observed in recent years, summarized in Table 2.

| Type | Attack type | Collaboration type | Description |

| A | Shared infection vector | Loose coordination | Deployment of backdoors via web shells, exploitation of vulnerable public-facing servers, or similar methods. Coordination is likely incidental, not intentional. |

| B | Coordinated supply chain attack | Strict coordination | Attacks leveraging supply chain compromise. Multiple intrusion sets collaborate to distribute backdoors via the same compromised vendor. |

| C | Deployment of a payload attributed to different intrusion set | Strict coordination | One group helps another deploy its malware in a target network. This is rare and highly coordinated. |

| D | Provision of an operational box | Strict coordination | One group prepares infrastructure (an "operational box") for use by another, often leveraging cloud services for C&C communications. |

Type A – Shared infection vector (Loose coordination)

This type involves the deployment of backdoors through web shells, exploitation of vulnerable public facing servers, and similar initial access techniques. In such cases, any observed coordination between intrusion sets is likely incidental rather than intentional.

Recently, Cisco Talos researchers have also reported on similar activity, reinforcing the prevalence of this technique. However, due to the loose operational structure, we assess that it remains difficult to determine whether any genuine collaboration or intentional access sharing has occurred in cases involving compromised public-facing servers.

Type B – Coordinated supply chain attack (Strict coordination)

This type involves collaboration through supply chain attacks. As highlighted in ESET’s report, we assess that it is unlikely for unrelated intrusion sets to independently distribute backdoors via the same compromised supply chain vendor without some level of prior collaboration or shared intent.

Type C – Deployment of a payload attributed to a different intrusion set (Strict coordination)

Group X actively assists Group Y in deploying its backdoors within an internal network. To our knowledge, this is an unprecedented event in China-aligned APT groups. The case we detailed at the beginning of this report belongs to this category. In September 2025, ESET published a report discussing some collaboration between Gamaredon and Turla, two Russia-aligned intrusion sets. Based on the public reporting, it seems that PteroOdd and PteroPaste, two custom malware families attributed to Gamaredon, deployed Kazuar, a malware attributed to Turla. We cannot confirm those statements, but if they prove to be true, this would be categorized in this Type C category.

Type D - Provision of an operational box (Strict coordination)

An evolution of Type C, Group X sets up an “operational box” for Group Y and abuses cloud services for C&C network communications. That way, it is not possible to base on network indicators for attribution. An example of this is the usage of VSCode remote tunnel feature as a RAT. We believe this type represents the most advanced collaboration model observed to date. This level of access sharing makes it very difficult to determine the identity of the actor behind the “operation box” if threat actor shared access with others.

The above summarizes the types of collaborative attacks we have observed so far. In the first section of this report, we presented real-world cases related to the Type C category.

| Collaboration attack | MITRE’s tactic sharing stage |

| Type A – Shared infection vector | Initial access (TA0001) |

| Type B – Coordinated supply chain attack | Initial access (TA0001) |

| Type C – Deployment of a third-party payload | Command and Control (TA0011) |

| Type D – Provision of an operational box | Command and Control (TA0011) |

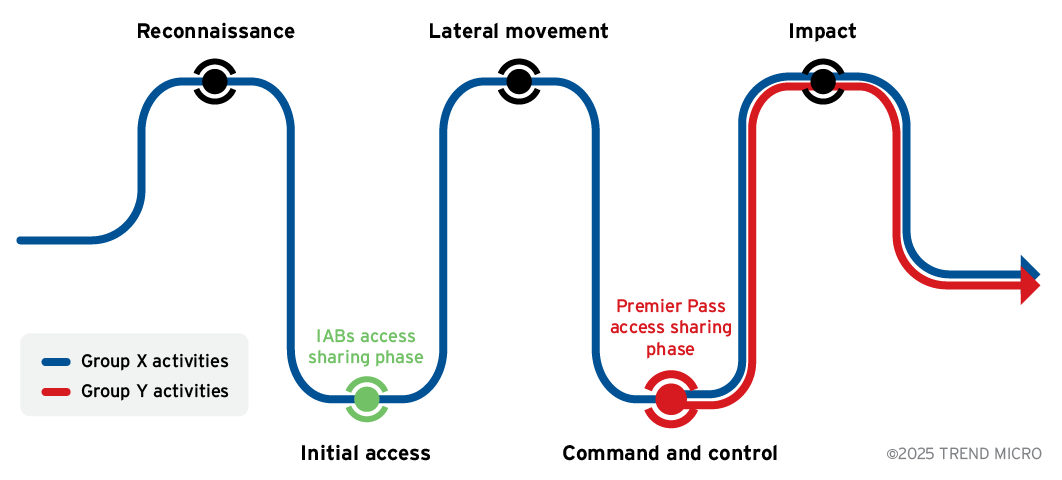

Table 3 shows the MITRE tactics at which the sharing between both intrusion sets happens. As seen in this table, the sharing in type C and D occurs in later stages of the MITRE matrix. This implies that the intrusion set responsible for the access sharing perform more steps from the kill chain in these scenarios, increasing the difficulty to draw a clear line between its actions and those belonging to the second intrusion set.

Emerging trend: The “Premier Pass-as-a-Service” model in APT operations

While it may challenge conventional thinking, we assess that once threat actors have successfully compromised a target and maintained persistence long enough to exfiltrate valuable data, a new operational model here tentatively referred to as “Premier Pass-as-a-Service” may be emerging within the ecosystem of China-aligned APT operations.

Our hypothesis stems from observations that diverge from typical initial access broker (IAB) behavior. Unlike IABs, who focus primarily on gaining and selling initial access to networks, the activities we’ve observed involve direct access to target assets. These unprecedented cases differ in scale, sophistication, and apparent purpose, prompting us to adopt the provisional term Premier Pass-as-a-Service to describe the phenomenon.

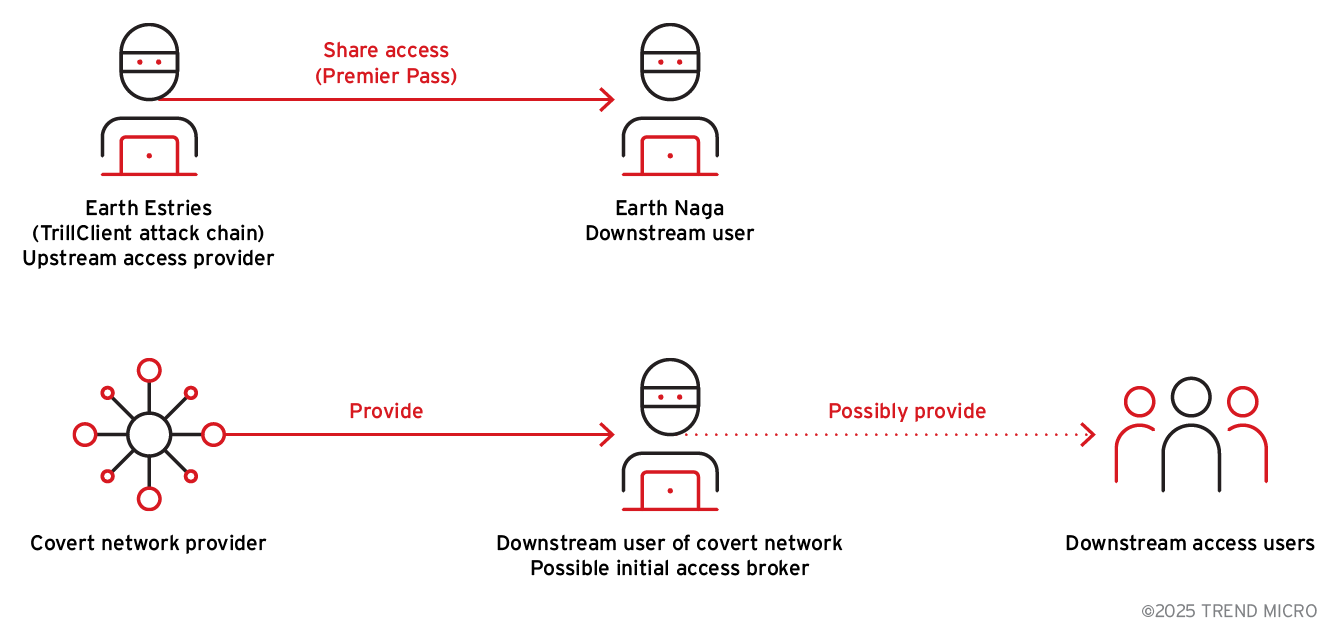

The strategic advantage of such a service lies in its efficiency. Premier Pass-as-a-Service provides direct access to critical assets, reducing the time spent on reconnaissance, initial exploitation and lateral movement phases (Figure 4). Analogous to a “fast pass” service at a theme park, in this context, the “facility” could represent any target asset.

In addition, we are aware that similar activity has been documented by Unit 42 in their research on Stately Taurus. Notably, they observed both Stately Taurus and an uncategorized ShadowPad cluster operating within the same network session, suggesting potential collaboration (this would be what we defined as “Type D” in an earlier section), shared infrastructure, or operational overlap.

Although the full extent of this model is not yet known, the limited number of observed incidents, combined with the substantial risk of exposure such a service entails, suggests that access is likely restricted to a small circle of threat actors.

The emergence of the Premier Pass model may also explain why some APT groups have seemingly gone dark in recent years. Rather than having disbanded or ceased operations, these actors may now be operating covertly through shared access infrastructure, or “operation boxes”, provided by this new service.

Beyond the Diamond Model of intrusion analysis

To address the increasing complexity in attributing activity among China-aligned APT groups, primarily due to the growing overlap and sharing of TTPs, we propose an enhanced analytic approach that emphasizes identifying each threat actor’s role within specific operational services. Whereas frameworks like the Diamond Model focus on certain key aspects – the adversary, infrastructure, capability, and victim – of a cyberthreat, this new approach provides a more granular view of actor behavior and relationships that may not be covered by traditional diamond models (Figure 5).

Key service categories

- “Premier Pass” or initial access broker

- Orb networks

- Private toolsets or exploitation frameworks

Operational role classification

- Developer – Responsible for creating or maintaining tools, malware, or infrastructure

- Provider/Broker – Facilitates access, distributes tools, or connects operational nodes

- Downstream user – Directly conducts operations using tools or infrastructure provided by others

Therefore, we utilize the approach to better understand the relationship between two threat groups through their respective roles.

- Upstream Access provider (Premier Pass): Earth Estries

- Downstream Access user (Premier Pass): Earth Naga

Security recommendations

The threat landscape is increasingly shaped by sophisticated, multi-group intrusions, as demonstrated by the collaborative operations between Earth Estries and Earth Naga. Defenders must adopt vigilant and multi-layered security strategies to counter risks such as suspicious file deployments, unauthorized remote administration, and targeted attacks on edge devices. To better detect and respond to these evolving tactics, they can apply mitigation practices such as:

- Staying alert to any suspicious file deployment activities, which may originate from compromised servers or lateral movement using leaked credentials.

- Verifying whether any legitimate remote administration tools have been installed and are being used by authorized users only.

- Carefully monitoring edge devices. A joint advisory containing general recommendations, as well as a methodology for hunting possible compromises, has been published in August 2025 by multiple governmental agencies.

Proactive security with Trend Vision One™

Trend Vision One️™ is the only AI-powered enterprise cybersecurity platform that centralizes cyber risk exposure management, security operations, and robust layered protection. This holistic approach helps enterprises predict and prevent threats, accelerating proactive security outcomes across their respective digital estate. With Trend Vision One, you’re enabled to eliminate security blind spots, focus on what matters most, and elevate security into a strategic partner for innovation.

Trend Vision One ™ Threat Intelligence

To stay ahead of evolving threats, Trend customers can access Trend Vision One™ Threat Insights which provides the latest insights from Trend ™ Research on emerging threats and threat actors.

Trend Vision One Threat Insights

- Threat Actors: Earth Estries, Earth Naga

- Emerging Threats: The Rise of Collaborative Tactics Among China-aligned Cyber Espionage Campaigns

Trend Vision One Intelligence Reports (IOC Sweeping)

Hunting Queries

Trend Vision One Search App

Trend Vision One customers can use the Search App to match or hunt the malicious indicators mentioned in this blog post with data in their environment.

Signatures for malware used in this campaign

eventName:MALWARE_DETECTION AND malName:(*DRACULOADER* OR *POPPINGBEE* OR *COBEACON* OR *CROWDOOR*)

Conclusion

Our research indicates that Earth Estries and Earth Naga have historically demonstrated significant differences in their TTPs. Therefore, we have tracked them as two separate intrusion sets. Although we have previously observed overlaps in the tools used by both groups, we believe the tool overlap is likely the consequence of a shared digital quartermaster rather than direct collaboration.

However, recent evidence of shared access and operational overlap suggests a notable shift, indicating the emergence of a new era of collaborative activity among China-aligned APT groups. This development marks a significant evolution in the threat landscape. The rise of coordinated operations presents an increasing challenge to accurate attribution and effective cyber defence. It is no longer sufficient to focus solely on the activities of individual threat groups. Instead, defenders must recognize and respond to the broader, evolving ecosystem of interconnected threat alliances.

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

The indicators of compromise for this entry can be found here.