Exploits & Vulnerabilities

LoRaWAN's Protocol Stacks: The Forgotten Targets at Risk

This report is the fourth part of our LoRaWAN security series, and highlights an attack vector that, so far, has not attracted much attention: the LoRaWAN stack. The stack is the root of LoRaWAN implementation and security. We hope to help users secure it and make LoRaWAN communication resistant to critical bugs.

Our LoRaWAN security series has so far outlined multiple security flaws, vulnerability issues, and entry vectors that attackers have been known to use. In this fourth part of the series, we talk about an attack vector that, so far, has not attracted much attention: the LoRaWAN stack. Although it is not a typical target, it is a critical one — the stack is the root of LoRaWAN implementation and security.

In both this report and our technical brief, we show specific techniques that can be used to find security flaws and bugs within the LoRaWAN stack. Attackers can use these methods to find and exploit devices, and we hope to highlight them to help stack developers or security consultants secure the stack and make LoRaWAN communication resistant to critical bugs.

An overview of LoRaWAN stack security

In our technical brief, we discuss LoRaWAN stack implementation and how to hunt for bugs in the different stacks using different techniques. We focus on fuzzing with AFL++ as well as introduce our fuzzing platform. We also explain how Qiling (based on Unicorn Engine) can be used in fuzzing and debugging exotic architectures. In addition, we explain how Ghidra's PCode emulation can be used when the architectures targeted are not supported by Unicorn or Qiling.

There are at least two types of stacks we can find with LoRaWAN:

- End-node stack. This is used to send uplink (UL) packets to the gateway, and on some occasions to send information to the end-node devices.

- Gateway stack. This includes all functions to connect to the network and forward packets coming from it.

There are also other stacks for the network and application servers, but we will not talk about them here, as we are interested in vulnerabilities that we can trigger from the radio interface. Indeed, attackers are more likely to access the radio interface because it is more exposed. It is also worth noting that attackers from the radio side will act as a kind of malicious sensor or gateway.

Finding bugs through fuzzing

While researching and experimenting with LoRaWAN stack security, we designed a fuzzing architecture to detect interesting bugs that attackers might be able to leverage. It can also be used to create more effective security for the protocol stacks of LoRaWAN and other protocols as well.

Fuzzing consists of generating and mutating inputs that we will feed our program to find flaws that can be exploited. This technique is a derivate of accidental bug finding since we introduce bad input data into our program that our parser is not supposed to handle.

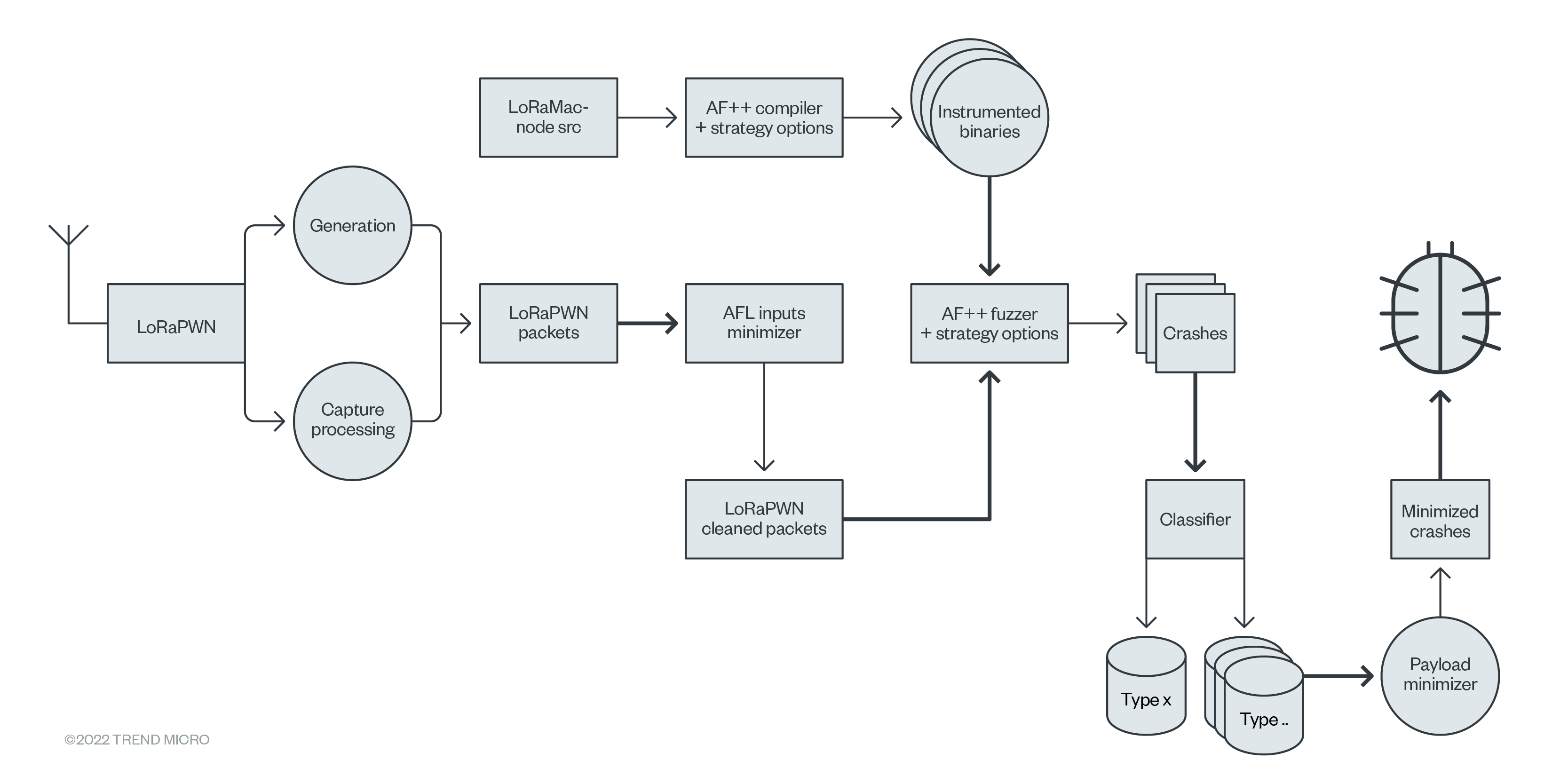

This architecture is fully explained in our technical brief, but an overview is illustrated here:

First, we compiled the code into something easily handled by a fuzzer. For our purposes, we used the generation method that will allow us to cover as many code paths as possible with legitimate and dumb fuzzing using the AFL++ framework (evolution of AFL). This supplies some instrumentation for mutating pseudorandom bits, bytes, and words.

We also attempted to collect every type of message that could be interpreted by the parser. We used the persistent mode to increase the fuzzing process speed from by x2 up to by x20. To deal with the amount of "uniq crash files" found in the repositories after fuzzing, we developed a classification method that can help users focus on the most interesting bugs first.

The code would then be compiled to a different architecture than x86-64, and with a specific cross compiler with specific options. So, if we try to prove the vulnerability by exploiting it, more time will be wasted adapting the exploit to the right architecture. Firmware can also be closed source, so we need different methods to continue automatic bug finding.

The following are two of the many methods that exist:

- Introducing stubs during debugging with GDB Pythons scripts, or with Frida on the few architectures supported by the tool

- Doing emulation with multiplatform engines such as Unicorn or Qiling

For this article, we have decided to demonstrate the use of the Qiling framework, which is a valuable tool used to quickly develop proof-of-concept emulators for multiple types of architectures. To demonstrate the tool in a straightforward way, and with symbols, we chose the LoRaMAC-node project, which is open-source but compiled in ARM. Qiling brings the UnicornAFL feature into the equation, so we not only use the framework to emulate, but also fuzz an emulated binary of a different platform.

When it comes to emulating and fuzzing gateways, the architecture that is often encountered is MIPS MSB, which is not yet handled by Unicorn and Qiling. However, it is possible to use Ghidra with official processors as an alternative. For example, emulation can be performed with extended processors like Xtensa on Espressif chips. We discuss this in more detail in our full technical brief.

Security recommendations for the LoRaWAN stack

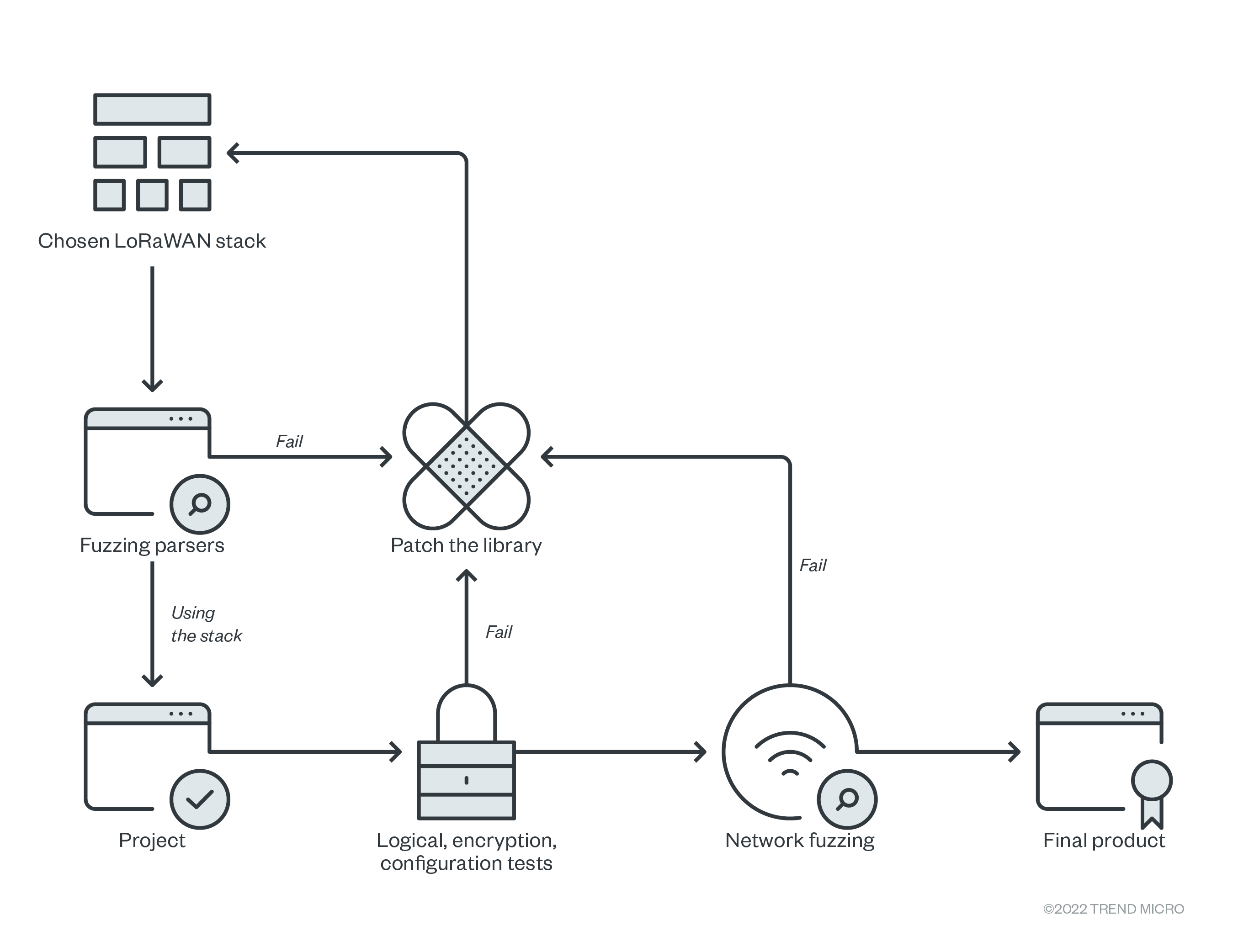

Stack developers and security teams handling LoRaWAN devices have to be vigilant and look out for vulnerabilities and memory corruption. The first step is to choose a protocol stack that has been approved by the community as well as tested by security researchers. Afterward, it is important to invest in fuzzing environments to check if the libraries used are resistant to the test cases scenarios that we outline in our technical brief.

The following image shows how fuzzing tests can be used in testing before releasing the LoRaWAN device:

LoRaWAN devices are often used in critical capacities such as smart city security, environmental monitoring, industrial safety, and much more. An attack that compromises these devices could therefore have a huge impact on the systems that rely on them.

We highlighted how the methods mentioned previously can be used to improve the safety of LoRaWAN devices, as well as how they can also be used by attackers to find additional (and well-hidden) attack vectors. However, because these stack security issues are quite complex, exploits are complicated as well. The attacker would need precise knowledge of the target, how it was compiled, or a dump of the firmware. Ultimately, it would take a dedicated and well-informed attacker to compromise LoRaWAN devices in this manner.

Despite the complexity of the attack, enterprises and users must protect their devices against this class of bugs. Because LoRaWAN technology is integrated into critical functions of connected factories and smart cities, every base must be covered and secured.

To read the complete report, download our technical brief here.